Politics of Anti-Austerity in Greece and Europe

Photo via Michalis Famelis, CC BY-SA 3.0

Photo via Michalis Famelis, CC BY-SA 3.0

“The new minister of finance declared that the country will no longer negotiate with the troika of the European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. Greece will not submit to the planned assessment of its bailout programme, even if that means not receiving a further €7.2 bn of troika funding this year. Indeed, the country no longer considers the troika to have a valid institutional status,” writes Costas Lapavistas, a SYRIZA member of the Greek parliament, on the Guardian.

Indeed, it seems that change is upon Europe. It is the sort of change that is making people uneasy, and rightfully so. The day after SYRIZA’s victory in the Greek legislative elections, the euro briefly slumped to an 11-year low in Asian trading. We may attribute a certain level of fear to mere speculation; however, there are some real possibilities about what SYRIZA’s victory signifies – namely a potential change in the direction of anti-austerity and post-liberal politics in Europe.

What is the nature of this change? In the past, during the early years of the troika regime, resistance in Greece took the form of strikes and demonstrations. The Greeks “organized more than 20 general strikes (of one or two days), mobilized huge demonstrations in Athens and in other cities” (Spourdalakis 2014; 356). These left-wing direct action mobilizations targeted national politics – natural, given the fact that it was the national government that passed the neoliberal policies in question.

As Mario Pianta and Paolo Gerbaudo point out, however, focusing one’s attention on the national government might not be the correct approach, especially within the context of the European Union. After all, Greece is part of the eurozone, which means that the ECB has greater control over Greek monetary policy. “In the past, national governments could respond to such issues with relative autonomy, however, in the present period of austerity required by Maastricht criteria, governments are unable (or unwilling) to stem the tide of unemployment by expensive propositions such as expanding the public sector” (Rotte 1992, cited in Bohrer II and Tan 2000).

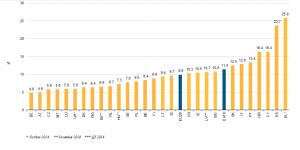

With this in mind, let us consider why government intervention might be necessary. Unemployment rates in Europe, especially for the southern states, are abnormally high. Greece has the highest rate with 25.8 percent, followed by Spain with 23.7 percent. These high rates of unemployment are part of a trend, caused by a change in political preferences. As the EU widened and deepened, social welfare policies gave way to more neoliberal policies, focusing on the liberalization of the European market and deregulation of trade. The after-effects of this change in policies can be seen visibly in Spain today, where the government has spent around 18.5 percent of its gross domestic product on saving banks from bankruptcy, despite facing a massive housing crisis (Barbero 2015).

Austerity is a choice, just like any other political decision. In face of a global economic crisis, rising unemployment rates, and other social crises, other action can be taken. For instance, the 2013 edition of the annual Euromemorandum calls for “limiting the freedom of action of the financial sector, enhancing the role of the ECB as lender of last resort, replacing austerity with policies of increasing public demand, wage support, full employment and shorter working hours” (Euromemorandum 2013, cited in Pianta & Gerbaudo 2013). It is a question of priorities, and given the claim that European countries are democratic states, that decision must be made by citizens, and not bureaucrats.

Now, let us go back to SYRIZA. How did SYRIZA, an openly left-wing party, manage to make its way into mainstream politics? One cannot make the argument that it has watered down its leftist politics just yet. A week into its time in the office, SYRIZA’s politicians are very adamant about their demands against austerity. In this sense, SYRIZA’s stance coincides with the stance of activists. Instead of jumping on the bandwagon of these activists and gradually replacing them, SYRIZA chose to provide “participatory support to the various forms of resistance to austerity and to the new mobilizing practices” (Spourdalakis 2014, 356).

One could call SYRIZA “populist,” but let us face it, the proper term one is looking for is “popular.” It is popular, because it claims to represent the wants and needs of the Greek population. It is popular, because it is different than the seemingly foreign troika that does not represent the needs of the Greek people. And this is just considering the national repercussions of a left-wing victory in a European country. In Spain, Podemos is inspired by SYRIZA’s victory and may mobilize more support in the coming months. In Italy, prime minister Matteo Renzi has gained a valuable ally in his resistance against austerity measures. Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the French Parti de Gauche, predicted a collapse of the ruling Socialist party.

Who is to say whether anti-austerity politics will succeed in Europe? Considering SYRIZA’s victory, maybe the question should be, who is to say they won’t? The future of anti-austerity politics may be uncertain; however, the past of the austerity regime is obvious: increased unemployment, increased precarity, decreased social security. The only thing austerity has done for Greece (and any other country whipped by the troika) was to send it spiraling down into debt.

There is nothing apolitical about economics – in other words, austerity is not inevitable. Not only is it not inevitable, but also it can be resisted and fought. At least, that is the message SYRIZA’s victory has sent to the 74 million unemployed people (twice the total population of Canada) living in Europe. Anti-austerity activists in Europe have always hoped to “transcend national boundaries” and “blossom into a European Spring” (Pianta & Gerbaudo 2013, 4). It didn’t happen in the past, but maybe spring 2015 will be different.

Works Cited

Barbero, Iker. “When Rights Need to Be (re)claimed: Austerity Measures, Neoliberal Housing Policies and Anti-eviction Activism in Spain.”Critical Social Policy (2015): 1-11. SAGE. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Bohrer, Robert E., II, and Alexander C. Tan. “Left Turn in Europe? Reactions to Austerity and the EMU.” Political Research Quarterly 53.3 (2000): 575-95. JSTOR. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Kassam, Ashifa, Henry McDonald, Stephanie Kirchgaessner, and Anne Penketh. “Syriza’s Election Victory in Greece – How Europe Reacted.”The Guardian. The Guardian, 26 Jan. 2015. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Lapavitsas, Costas. “Syriza Has Bold Solutions to the Forces of Austerity That Are Strangling Europe.” The Guardian. The Guardian, 2 Feb. 2015. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Pianta, Mario, and Paolo Gerbaudo. “In Search of European Alternatives. Anti-austerity Protests in Europe.” Thesis. London School of Economics, 2013. LSE Projects on Subterranean Politics in Europe. Selected Works, Jan. 2014. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

RT.com. “Greece’s Syriza Govt Could Pose Greater Risk to Global Economy than Middle East Conflict – Osborne.” RT.com. RT, 2 Feb. 2015. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Smith, Helena. “Syriza’s Historic Win Puts Greece on Collision Course with Europe.” The Guardian. Ed. Ian Traynor. The Guardian, 26 Jan. 2015. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.

Spourdalakis, Michalis. “The Miraculous Rise of the “Phenomenon SYRIZA”” International Critical Thought 4.3 (2014): 354-66. Taylor & Francis. Web. 3 Feb. 2015.