“Comfort Women”: Japan and Neighbour Relations

70 years ago, the Pacific side of the Second World War officially ended with Japan’s surrender after the landing of two atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Japan’s defeat marked Korea’s liberation from 35 years of Japan’s colonization. This year, 2015, is quite special. It is the 70th anniversary of Korea’s independence from Japan and the 50th anniversary of the Basic Japan-South Korea Treaty that normalized the diplomatic and economic relations between the Republic of Korea (South Korea) and Japan after the war. Relations between Seoul and Tokyo have always been strained, as territory disputes and nationalism in both countries built tensions since the war, particularly on the matter of “comfort women” during the war.

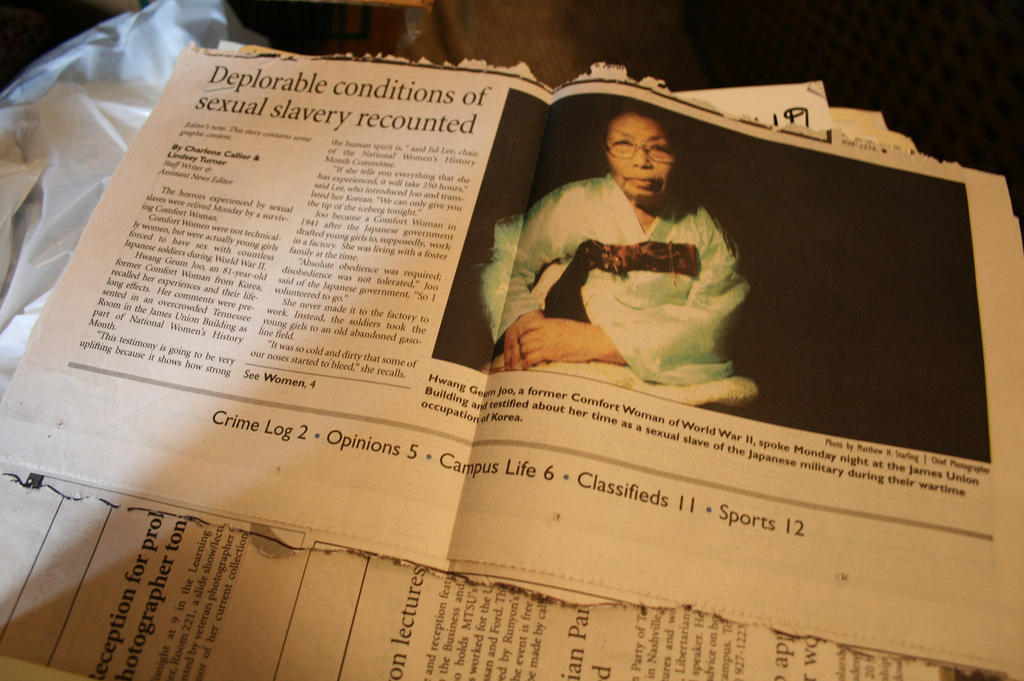

“Comfort women” (lanfu in Japanese, uianbu in Korean) refers to women who provided sexual services to officers and soldiers during the war due to coercion. “Comfort women” were widely established after the Nanjing Massacre. Most of the “comfort women” were young Chinese and Korean girls, with others arriving from all over Japanese colonies in Southeast Asia.There were some young Japanese girls who participated, but they were not referred by this same title. They were ranked by race, and for obvious reasons, the Japanese women were treated with relatively more privileges. The concept of “comfort women” is controversial due to the matter of consent. The Japanese government and some historians claimed that those who were part of “comfort women” joined voluntarily, and even argues that the “comfort women” never existed despite photographic evidence and first-hand accounts from victims and witnesses. Others argue that the majority were forced into the sex trade. Some also point out that even if the girls volunteered to join, they were deliberately deceived by the Japanese recruiters and believed that they would be serving as “nurses” near the front lines. Many of these women also first joined Japanese forces to help support their family in the midst of harsh Japanese control over local economy.

The number of “comfort women” was never officially clarified; it ranges from the hundreds to thousands. Even decades after the war, the subject matter is extremely diplomatically delicate, especially in relations between South Korea, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Japan.

One reason that “comfort women” made South Korea and Japan’s relationship frosty for decades is the lack of trust. Much of distrust is emotionally driven between the people from both countries. According to a Joint Japan–South Korea Public Opinion Poll (2014), over half of both South Koreans and Japanese have mutually unfavourable impressions on each other. Anti-Japanese sentiments were high in South Korea due to the brutality and abuse during the colonial period, especially in the case of “comfort women”. Combining diaries and testimonies, Yoshiaki Yoshimi, a Japanese historian, argued that many young Korean girls were coerced, deceived or, in some cases, kidnapped to be part of the “comfort women”. This historical fact drives a wedge between the Japanese and Korean governments, which hinders reconciliation on the emotional issue of “comfort women”. Although Yohei Kono, Chief Cabinet Secretary in 1993, had issued a cursory “formal” apology recognizing the army’s indirect and direct involvement in comfort facilities, South Korea finds the apology insincere. Henceforth, South Korea is still demanding an official apology from Japan.

On top of this mutual distaste for each other, Japan and South Korea have different interpretations of this historical event. Recently, Japan has openly permitted a publisher of history textbooks to remove all detailed descriptions about “comfort women”. Moreover, 19 historians and scholars protested for revisions about “comfort women” in American history textbooks. Ikuhiko Hata, a historian, claimed that there are “many errors” in the explanation about brothels during the war. Japan appears to be in denial of the “comfort women”, while Japan believes that South Korea is overreacting.

Japan’s denial has detrimental effects on its relationship with China as well. Tensions increased between Japan and China whenever a Japanese Prime Minister paid their visit to the Yasukuni Shrine, a temple dedicated to honoring wartime leaders during the Second War World. While Japan claims that this temple was built to honor the war heroes, the Yasukuni Shrine is a place to officially glorify wartime criminals for China, Korea, and many other victims of Japanese brutality. Many of the soldiers honored at the shrine were also heavily involved in facilitating the trade of the “comfort women”, especially following the Nanjing invasion. The shrine also symbolizes militarism that brought Japan into ultra-nationalistic country. Therefore, the current Prime Minister of Japan, Shinzo Abe, visiting the shrine provokes anger from China and South Korea as it gives the impression that the Japanese lacked sincerity in their previous (however few and colloquial) apologies.

On the other hand, fully admitting or apologizing on the issue of “comfort women” would be extremely challenging for the Japanese government. The majority government, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) — a conservative party — are nationals and conservatives who believe women joined the “comfort women” in a voluntary manner like brothels in any other war. A nationalistic politician, Toru Hashimoto (Osaka’s mayor), even remarked that “comfort women” were necessary for the soldiers’ wartime discipline. He argues that “comfort women” was a policy implemented to decrease the frequency of rape during the Imperial Japan’s invasion. Throughout Japan’s modern history, the cabinet members have played a powerful and influential role on the Prime Minister. Therefore, Shinzo Abe has a difficult task to do — keeping his cabinet satisfied while improving diplomatic relations with their neighbour on the matter of “comfort women”.

After all, reconciling the “comfort women” issue will be a challenge to the current Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, to seek a common ground between the conservatives and international relations. While Japan’s domestic political culture is still nationalistic and puts pride in the achievements during the war, Japan’s relationship with South Korea and China is highly significant for obvious political and economic reasons. This dilemma will land on the hands of Shinzo Abe and whether he has the intelligence to resolve the tensions on “comfort women” without losing support from his cabinet members.

Bibliography

- The 2nd Joint Japan-South Korea Public Opinion Poll (2014) (Analysis Report on Comparative Data). (2014). from The Genron NPO http://www.genron-npo.net/en/pp/archives/5142.html

- China, Koreas blast Japan for “comfort women,” Yasukuni at UN Women. (2014, January 22, 2014). Retrieved from http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/kyodo-news-international/140122/china-koreas-blast-japan-comfort-women-yasukuni-at-un-

- Fifield, A. (2015, February 10, 2015). Shinzo Abe’s government plays down historians’ concerns over South Korea’s ‘comfort women’ in WWII. Retrieved from http://www.smh.com.au/world/shinzo-abes-government-plays-down-historians-concerns-over-south-koreas-comfort-women–in-wwii-20150210-13adis.html

- Nelson, H. The New Guinea Comfort Women, Japan and the Australian Connection: out of the shadows. from http://japanfocus.org/-Hank-Nelson/2426

- Service, K. N. (February 17, 2015). Korea Will Glorify This Year as Year of Victory: Koreans’ Body in Germany. from http://www.kcna.co.jp/item/2015/201502/news17/20150217-06ee.html

- Spitzer, K. (2012, December 11, 2012). Why Japan Is Still Not Sorry Enough. from http://nation.time.com/2012/12/11/why-japan-is-still-not-sorry-enough/

- Suk, L. Y. (2015, February 8, 2015). South Korea-Japan ties still fraught by ‘comfort women’ issue. from http://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/asiapacific/south-korea-japan-ties/1643166.html

- Takahashi, K. (2012, September 12, 2012). Treaty offers way out for Tokyo and Seoul. from http://www.atimes.com/atimes/Japan/NI12Dh02.html

- Ueno, C. (2006). The Place of “Comfort Women” in the Japanese Historical Revisionism. from http://www.sens-public.org/spip.php?article196&lang=fr