Corbyn’s UK and Foreign Policy – Rational or Ridiculous?

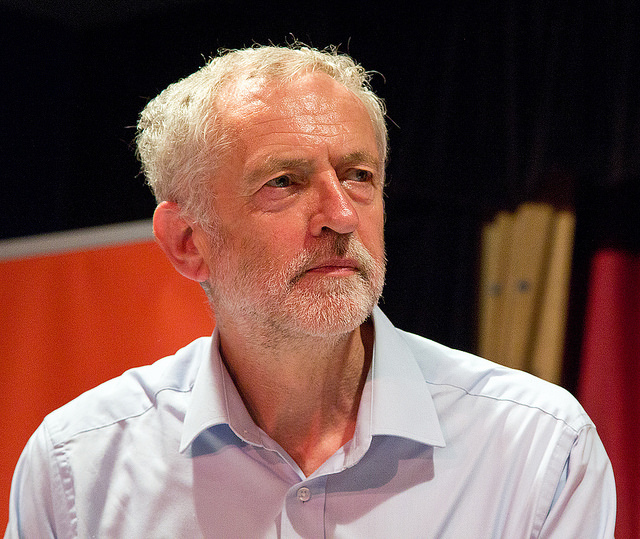

Jeremy Corbyn, the quiet, haphazard and dishevelled Cinderella of British politics, has been dominating the news in the UK ever since his unforeseen sponsorship to run in the Labour leader elections. Since that day, he has gone on to capture the imaginations of Britain’s discontented labour youth and has catapulted himself into the position of Labour leader despite having 100-1 odds placed against him by bookies across the country.

Corbyn demands controversy with his reputation as one of Labour’s most radical and difficult backbenchers since the mid 1980s. He has taken strong stances against Labour’s direction in recent years as well as making friends with some contentious people, such as Gerry Adams, who is the leader of the Irish Republican Army’s political wing, Sinn Fein, and who openly supports Hamas, the Iranian-backed Palestinian militant freedom movement. [1]

In light of all this, all eyes are on Corbyn to see his stance in international politics, and, particularly, the UK’s involvement in the global political sphere. Corbyn has been refreshingly honest in his stance, declaring that he would not renew the Trident, UK’s nuclear submarine programme; disapproving of NATO and US involvement in European affairs (namely the Russo-Ukranian crisis); and openly standing against intervention in Syria, a move that has caused ripples across Westminster as a huge majority of Labour MPs seek to support the motion in a large inter-party initiative to finally engage the Syrian issue.

Although one can applaud Corbyn’s boldness as the new kid on the block (although he is very much an old player in the British political scene), you have to question his political intellect. It is one thing to disagree with your party line as a backbencher and quite another to oppose it as the figurehead of the MPs you seek to represent. Moreover, it’s a bold move to call Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as ‘not entirely unprovoked’ as he did in an article for the Morning Star newspaper in April 2014. Corbyn looks like he has a lot to learn from those who have experienced the limelight in Westminster as well as the weathered party leaders with years of experience in taming a rowdy and disagreeable party.

Having said that, is Corbyn really that wrong when it comes to foreign policy? One contentious topic for politicians on both sides of the aisle is Trident, the UK’s sole nuclear deterrent based up in Scotland, which Corbyn hopes to discontinue if he becomes Prime Minister. It costs the British public roughly £2.4 billion (around CAD$ 5 billion) every year to maintain the programme – a point of serious contention to those who wish to see a decrease in the defence budget to allow for increases in benefits and social amenities. Trident renewal would cost the British public £34 billion alongside £130 billion in upkeep over the thirty-year period. Scrapping renewal could save over £83 billion in revenue to be used in maintaining social benefits such as the faltering National Health Service (NHS), unemployment and child benefits as well as allowing for numerous amelioration programmes across the UK. Now, Corbyn doesn’t look like he is being as radical as once thought, but really, rather rational.

Trident aside, Corbyn has also called for no intervention in Syria, a move that has estranged the Labour party from him once more and widened the chasm between leader and members. However is this really unreasonable? In a rather counter-intuitive move, David Cameron feels that bombing Syria will stop the influx of refugees already escaping the bombing in Syria which comes in addition to the past year of bombing runs by the US, and Russia’s current involvement in the conflict. That sounds like the more unreasonable position.

It’s arguable that Syrian intervention would result in even more damage: Turkey is under fire for engaging with Syrian militia and ISIS troops across the border, Russia has just been critiqued for its airstrikes and backing of pro-Assad forces, and Syria has grabbed the attention of its neighbours as the flashpoint for what could result in a huge geographical conflict.

It seems that whenever UK sticks its face into foreign affairs, we see an immediate backlash and a lasting sense of discontent that correlates into aggressive organisations and regimes arising from the rubble that we leave. This is the involvement that Corbyn is fighting and it seems to be backed up by some irrefutable evidence. An interesting parallel to look at would be Tory Benn’s speech to Westminster before the vote on intervention in the Iraqi war. Benn was a passionate and opinionated man, whom I would argue (with the benefit of hindsight) was able to predict the disaster that followed after British intervention in Iraq. It is a foreshadowing and a warning that the UK should take seriously. Non-interventionists were ignored then and it looks like they are being ignored today in a cruel repetition of history.

Despite supporting Corbyn in the aforementioned issues, in my eyes he has had his fair share of political setbacks. In fact, Corbyn manages to estrange those that would support him with comments and sentiments that make his media team’s toes curl.

Corbyn tweeted to a follower that they should watch Russia Today, the leading government-run news channel, for ‘objective’ news. He has called for NATO to start minding its own business and to cease intervening so frequently in international affairs. He seems to support Hamas’ and the IRA’s militancy, two organisations known for causing countless civilian deaths. As I mentioned, Corbyn even had the audacity to claim that Ukraine provoked Russian aggression. Here, Corbyn needs to re-evaluate his stance and remember that Labour doesn’t spell international seclusion but rather humanitarian intervention, if he is either going to win a general election, or even stay in as head of the Labour party.

Ideally, I would see Corbyn stand by his policy on Trident and Syria, but emphasise a new initiative to utilise the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations (UNDPKO) to the best of their abilities, allowing for multilateral intervention in conflicts that maintain a distinctly non-unilateral motive. However, the likelihood of this is infinitesimally small. Corbyn voted against UN intervention in Afghanistan and Libya, and action to stop Slobodan Milosevic’s ethnic cleansing in Kosovo resulting in some of the worst conflicts of the modern day – another blot against UK’s foreign policy record.

Mike Gapes, the Labour MP for Illford South, succinctly puts this argument into words in one of his online editorials for ‘Left Foot Forward’, a Progressive political blog. He writes, “Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-nuclear, anti-NATO, anti-American, anti-interventionist, and Eurosceptic message will be welcomed by some in this country and by some abroad. But it is unlikely to be welcomed by Kurdish and other anti-Da’esh forces in Iraq, by anti-Assad democrats in Syria, by democratic Central European NATO states like Poland, or by Ukrainians. Above all, though, it will be resoundingly rejected by the British people, and lead Labour in 2020 to an even worse defeat than we collectively suffered in 1983.” [2]

Gapes is right. No matter how you look at it, Corbyn has a big decision to make; whether he decides to adjust his perspective on international politics or continues to plough his own furrow and pull the hesitant Labour party down a path of hyper non-interventionism. It all comes down to treading a middle path and that is something Jeremy Corbyn is notoriously bad at.

Citations

[1] Gilligan, Andrew, Jeremy Corbyn, friend to Hamas, Iran and Extremists, (18th July 2015), http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/labour/11749043/Andrew-Gilligan-Jeremy-Corbyn-friend-to-Hamas-Iran-and-extremists

[2] Gapes, Mike, What would a Jeremy Corbyn foreign policy mean for Labour?, (13th August 2015), http://leftfootforward.org/2015/08/what-will-a-jeremy-corbyn-foreign-policy-mean-for-labour