The Evolution of Political Consciousness in Hip-Hop

From my first exposure to hip-hop in middle school to Eminem’s “mom spaghetti” verse on “Lose Yourself”, I was immediately captured by the ingenious wordplay accompanied by an intense and clean beat. Yet, interestingly, this duality between the grating combination of words and a fast-paced beat was met by a juxtaposition of a soothing and relaxed atmosphere. Hip-hop became and still remains my favourite genre. I began to diversify my exposure to different artists only to further deepen my fascination and enjoyment for the genre. Hip-hop has been the platform where I take refuge to escape the harsh, stressful periods of life and school. The multi-colored and in-depth mastery of wordplay creates a vivid and tempestuous expression of messages that can be relatable when I find it difficult to formulate or express my sentiments in words. More importantly, the diversification of emotionally charged messages is an instrumental and core component of the genre for a political, cultural and social critique of the status quo.

Early Beginnings of Hip-Hop

The origins of hip-hop can be traced back to the 1970s in the United States, mainly in the Bronx, New York by various African American communities. Figures such as DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa, and Grandmaster Flash have been accredited as pioneers of 20th Century Hip-Hop. Since the inception of the genre, early pioneers have been influenced by a combination of music and traditions from different cultures – mainly the Caribbean and Latin America. The increasing popularity of block parties, especially in African American communities, during the 70s served as the breeding ground for Hip Hop artists to experiment with different musical elements and refine their sound.

Block parties also served as outlets of social and political commentary for the African American population. Hip-hop became the voice and medium for African Americans to express their opinions and concerns in a society where racial discrimination and segregation were institutionalized. It was the only form of commentary that enabled disenfranchised African American communities to express their frustrations and where their own voices would be heard. For instance, Afrika Bambaataa established the Universal Zulu Nation, a street movement with hip-hop as their basis that aimed to prevent teenagers from gang culture, violence, and drugs.

As time passed, Hip Hop continued to progress and flourish, the 1980s was considered “The Golden Age of hip-hop”. While preserving its original musical roots, the genre continued to explore and incorporate various new styles and elements that led to diversification; the Rolling Stones said it best: “it seemed that every new single reinvented the genre.” This solidified hip-hop’s position into mainstream media. On the other hand, this enabled charged political and social messages from African American communities to become widespread across Northern America.

Rapping evolved from being a casual, verbal duel to communal verbal messages about deep-rooted and structural conundrums of the status quo. An overarching issue that many artists during this period explored were largely related to the film movement of “Blaxploitation,” which focused on African American individuals as protagonists and the main focus in films to highlight their socioeconomic struggles and racial discrimination that they faced.

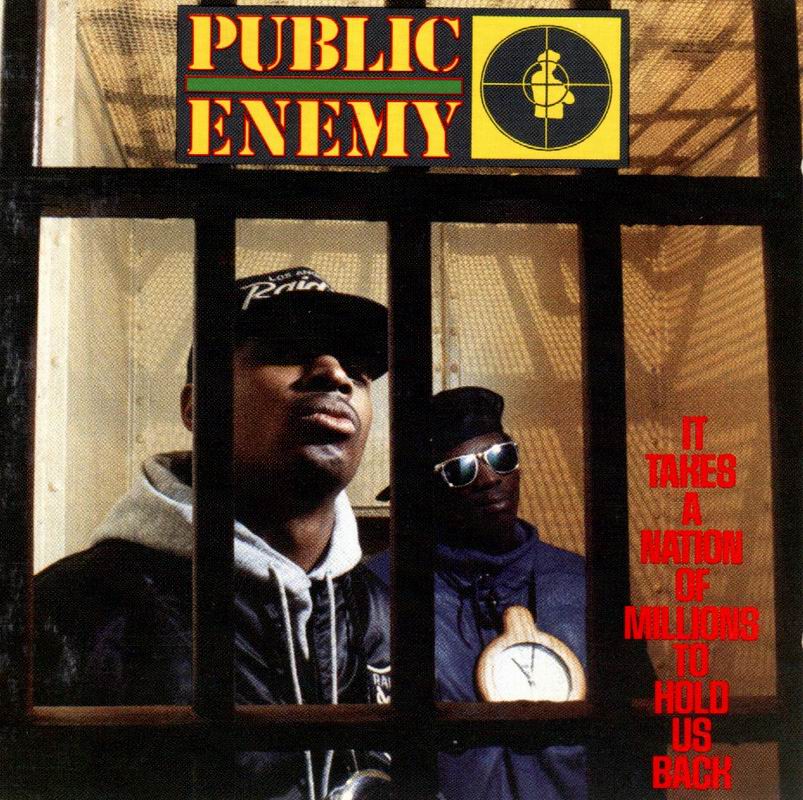

Public Enemy’s 1989 hit-single “Fight the Power” challenges the structural issue of racial discrimination that minority groups, specifically the African American population, had to face. The infectious hook of the song, “Fight the Power/ we’ve got to fight the powers that be”, essentially criticises the government for corruption and social injustice for stripping power and rights away from the poor. Public Enemy openly critiques those who deny the existence of racial discrimination. Consequently, in order to tackle this conundrum, Public Enemy calls for black emancipation to expand their vision and understanding of discrimination, in essence “awareness”. The group also openly criticise prominent figures and symbols of white society; for instance: “Elvis was a hero to most/ but he never meant shit to me/ straight up racist that sucker was/ simple and plain..”

The emergence of prominent hip-hop groups such as Public Enemy led to the foundation of the sub-genre ‘gangsta-rap’ that consists of heavier flows and bars complemented by greater profanity and controversial wordplay. This particular style of hip-hop was met with a wave of criticism for promoting violence, gang culture, racism, misogyny, homophobia, vandalism, shootings, and substance abuse. Gangsta-rap’s popularity and relevance reached such a high level that even Presidents such as Bill Clinton and Ronald Raegan had to enter the conversation. They employed a rhetoric that interpreted hip-hop as a weapon that threatened the stability of the country with a heavy emphasis on attacks on the ‘American Dream’ and law enforcement. Chuck Philips, a well-known investigative journalist who extensively covered the ’90s hip-hop scene, has highlighted that criticism against the genre as a whole was largely derived from the intrinsic nature of hip-hop as historically and continuously anti-establishment, elucidating the contradictions in North American society. As a consequence, the White House’s mandate is unstable and threatened.

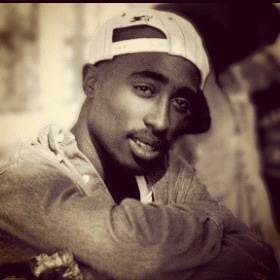

By the 1990s, the political consciousness of hip-hop did not run out of steam. The genre continued to develop and diversify itself to offer deeper and more complex social commentaries on various issues besides racial discrimination. Police brutality became one of the main themes for commentary with NWA’s Straight Outta Compton serving as the flagship account on this issue. NWA’s “Fuck Tha Police” criticised the judicial system along with the police force for their brutality, racial profiling and unequal treatment of young African American adults. Artists also concentrated on social commentaries which recalled their struggles of growing up in harsh neighbourhoods and living off social welfare; in doing so they hoped to educate deprived communities on the everyday wisdom that includes family values, hard work and respect. Soon, legends such as Tupac, The Notorious B.I.G. and Nas entered the game and shook the structural foundations of society.

In his iconic track, “Changes”, Tupac showcases his wordplay wizardry with personal accounts of police brutality, institutionalized racism as well as the war on drugs that plagued disenfranchised black communities. As well as highlighting the inconsistencies and anti-black bias of the justice system. Tupac spilled verses that criticized neoliberal economic policies motivating people to sell drugs to kids for profit: “you gotta operate the easy way/ I made a G today but you made it in a sleazy way/ sellin crack to the kids/ I gotta get paid well hey, but that’s the way it is”. The end of the verse highlights the drug issue that has been institutionalized as a consequence of a neoliberal-driven economy. Tupac not only presents this issue purely from an economic standpoint but also incorporates elements of morality to accentuate that, from an ethical standpoint, selling drugs to kids has been normalized. On the other hand, Tupac also criticises the administration for its failure to divert necessary resources and consideration on domestic issues such as poverty: “It’s war on the streets and a war in the Middle East/ instead of war on poverty/ they got a war on drugs so the police can bother me/ and I ain’t never did a crime I ain’t have to do.” Tupac spearheaded the rap rhetoric that focused on addressing political, social and economic problems.

Hip Hop at the Contemporary Stage

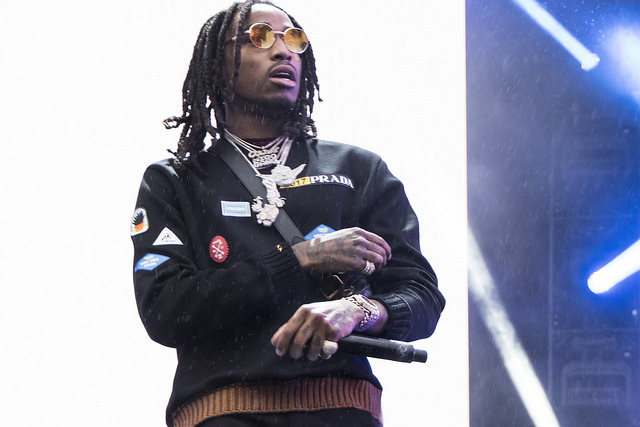

With the rise of ’90s gangsta rap, pioneered by the likes of Tupac and NWA, the genre succeeded punk as the de-facto platform for anti-establishment commentary. At the turn of the century, it was anticipated that such success and critique would translate and continue to flourish. However, this was not the case. What seemed like out of nowhere, hip-hop appeared to have lost its direction and faced somewhat of an existential crisis. The rise of commercialization, commodification and consumerist behavior had critically endangered the anti-establishment foundations that the genre was built on. It went through a radical metamorphosis; the topics of commentary drastically changed from political and socioeconomic issues to topics on materialistic boasting, sex, and drug abuse. In essence, hip-hop artists decided to do away with the genre’s political consciousness.

Criticisms against contemporary hip-hop are undoubtedly sound, although what this reveals is that despite neglecting its roots, this shift reflects various structural and existing problems that have plagued the establishment. Commercialisation, as well as commodification, has fostered a new generation of artists such as Lil Yachty, Lil Pump and Chief Keef, more commonly referred to as “mumble rappers” who focus on following popular trends in order to increase their profit along with fame. The repercussions are monumental for the diversity (or lack thereof) of the genre. In a 2015 interview, Snoop Dogg shed light on this issue and argued that contemporary hip-hop artists are sonically identical. For instance, Cardi B’s flow on “Bodak Yellow” is identical to Kodak Black’s on “No Flockin.” Every track on Lil Pump’s self-titled debut mixtape is virtually the same, especially in subject matter and flow. In retrospect to the 80s and 90s, each artist developed their own specific and unique music style that sonically contributed to the genre. Unfortunately, this contemporary tendency of bandwagoning has hampered artistic experimentation as a whole and created a linear, repetitive path for upcoming artists to follow.

Today, mumble rap dominates the rap industry. However, this does not mean that hip-hop has lost its foundations and original identity entirely. The recent cases of police brutality against the black population and people of colour, such as the Michael Brown and Charleena Lyles cases, have reignited the spark for artists to return to the socio-political roots of hip-hop and reawaken its political consciousness. Artists such as Kendrick Lamar, J Cole and Joey Bada$$ have been the spearheads of this revival. Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly was a cultural milestone that featured commentaries on topics such as black empowerment, social injustices, and individualist wisdom; reflecting that political consciousness in the genre is alive and well.

In “Hood Politics”, Kendrick vividly depicts the harsh realities and experiences from growing up in the “hood” environment. For instance, in the chorus, Kendrick spills out “boo boo” in an attempt to portray the tense and highly violent politics between neighbours living in the hood. This imagery is further sharpened by his metaphorical use of “deuce deuce” which references to a .22 caliber gun to elucidate the fast escalation of tensions in the hood. At the same time, he also conveys that this draconian atmosphere has been a cross-generational conundrum; preceding rappers, including himself, were brought up in a contentious and detrimental atmosphere. Kendrick also jumps into the police brutality discussion and points out that “the LAPD gramblin, scarmblin, football numbers slanderin” to depict the unnecessary shootings of African Americans. Besides police brutality, Kendrick illustrates the contradictions and irony that plagues the White House administration, specifically “red states versus a blue state, which one you governin’?“. This is a reference to Jess Ventura’s DemoCRIPS and ReBLOODlicans: No More Gangs in Government novel that highlights how politicians are corrupted by corporate incentives. As a consequence, this destroys the fairness of legislative, electoral processes and divides the government into separate blocs; each pursuing their own respective interests instead of the people’s. Kendrick provides a similar argument with a slight twist; instead, the administration’s negative perception and portrayal of African American communities have been hypocritically responsible for the distribution of drugs and dividing the people into separate contentious blocs.

Meanwhile, in Kendrick Lamar’s recent album, DAMN., he continues to build on the success and commentaries that To Pimp a Butterfly explored. In “Element”, he alludes to photographs and other works by Gordon Parks, a prominent photojournalist who documented the socioeconomic situation of African Americans during the mid 20th century. In doing so, Lamar attempts to portray the lives and experiences that they face, similar to Parks. On the other hand, he also questions the contemporary status of mumble rappers when the “last LP I tried to lift the black artists/ but it’s a difference between black artists and wack artists.” He openly criticises how contemporary artists have focused on seeking approval and success from following trends instead of being themselves, to remind artists that Hip Hop consists of finding and developing your own voice and music style.

Besides the perpetual issues of police brutality, socio-economic difficulties and corrupt government officials, the ushering-in of Trump’s administration has further fuelled the genre to provide more substance and commentaries on political and social conundrums. In reaction to Trump’s inauguration, artists have criticised his lack of experience in government administration and mocked his irrational, discriminatory and contradictory policies. For instance, Joey Bada$$’s Land of the Free explores the contradictory and structural implications in America, a direct paradox set against the title of the track. He makes a clear statement against Trump, who “is not equipped to take this country over”. On the other hand, he highlights how Trump’s administration has made no substantive effort to improve nor address the institutionalised problem of racism. As a consequence, this lack of concern has made discrimination as well as hate speech possible against minority groups, a “full house on my hands, the cards was dealt/ three k’s, two a’s in Amerikkka”.

Despite the resurgence of hip-hop’s political consciousness, consumerism and commercialism have limited the genre towards the latest trends to secure profit and fame. As a consequence, the new generation of artists has followed a linear path instead of diversifying and constructing their own unique style and identity. Contemporary hip-hop was not what it once was during its ‘Golden Age’, but this does not mean that it cannot return back to its glory days.

Edited by Sarie Khalid