Malaysia’s Vision 2020

In the bustling streets of Kuala Lumpur, high sky rises are seen throughout the downtown area. The rapid expansion of the Malaysian capital is reflective of the country’s simultaneous economic growth. Even among the other bustling regional South-East Asian countries, Malaysia stands out as what seems to be an incredible success story.

Its economic performance can be easily attributed to Malaysia’s Vision 2020. Vision 2020 is the economic policy established by Malaysian policy-makers to achieve a developed status by the year 2020. This plan was introduced in 1991 and entails both economic and social requirements. Specific targets were set: notably 7% GDP growth per year, Gross National Income per capita of $15,000 USD and the complete eradication of poverty. The approach taken was premised on the assumption that in order to achieve rapid economic growth, socio-economic goals needed to be set. Thus, these policies strongly emphasized policies aimed at poverty elimination.

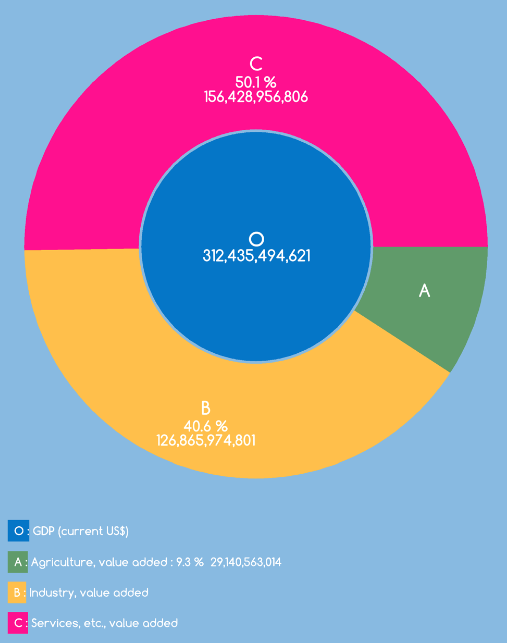

With less than five years remaining for Malaysia to reach its goal, an evaluation of its likelihood of success is enlightening. After the policy was implemented in there has been a 339% increase in GPD in 2014 from 1994, from US$74,481,194,985 to US$312,435,494,621. The annual GDP growth rate has averaged at approximately 5% for the last 15 years, indicating high and sustainable levels of growth. Income per capita was US$10,060 in 2013, up about 50% from US$6,700 in 2009. This data clearly indicates upwards-macroeconomic trends in Malaysia and improvements in its economy.

In order to understand where this economic growth is derived from, it is necessary to look at their trade portfolio. In the Malaysian economy, international trade is fundamental, accounting for 85% of their GDP. This represents an immense emphasis on the export-led growth in Malaysia. Emphasis on export was predicated on the need to expand its share of trade in its GDP, to exploit new consumer markets, and to focus on industrial growth. To this effect, Malaysia maintains itself as a net-exporter, which means it maintains the level of its exports above its imports, successfully attaining positive current account balances since 1998. Malaysia’s primary trading partners are China, Singapore, the European Union, Japan and the United States. In 2013, 80% of its trade was between the same 14 trading partners.

Malaysian policy-makers recognized that in order to achieve high levels of economic growth, promoting the value-added manufacturing sector would be necessary. By identifying their competitive advantage with low-cost technical labour in the new emerging consumer markets, industrial policies were pursued and a reorganization of the economy with emphasis on manufacturing was required. However, Malaysia lacked the necessary capital to pursue such industrialization policies and consequently sought foreign investment. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) has been crucial for Malaysia’s economic transformation, as it is the primary fuel for many developing economies. In 2011, FDI inflows accounted for 5.2% of Malaysia’s GDP, up from 3.3% in 2008. However, to attract further investment, the Malaysian government has implemented sector-specific policy measures to increase their competitiveness. By making improvements to infrastructure, offering subsidies, and increasing research and development expenditures, there was a subsequent increase in foreign investors in the targeted sectors.

With this targeted investment, there has been an impressive growth in the electronics and electrical sector, petroleum gases and oils, machinery and transport equipment, and in its services sector. Malaysia’s largest export in 2011-2013 was in the electronics category, and in 2013 it accounted for 32.8% of exports and employed 27.2% of the total labour force. In addition, Malaysia’s natural gas and oil resources have contributed to an average of 20% of its GDP over the last decade. Lastly, the rapid expansion and high levels of investment in the services sector make it account for an extremely significant portion of its economy, at just over 50% of the economy in 2014. (Graph)

Needless to say, this FDI in and expansion of these sectors have contributed to the overall growth of the Malaysian economy. Malaysia’s emphasis on export-led growth has led to a surge in Free Trade Agreements (FTA) between Malaysia and its global partners: the country has ratified 11 FTAs in the less than ten years. These include bilateral agreements with Japan, Australia, Chile, India, New Zealand, and Pakistan, as well as multilateral agreements between ASEAN (of which Malaysia is a founding member) and China, India, Australia-New Zealand, Korea, and Japan. These initiatives represent Malaysia’s commitment to trade openness, drive for greater competition, and desire for increased market access.

As a result of these upwards-macroeconomic trends, positive trends can also be identified in human development indicators. Due to increased government expenditure on education and health, there have been significant improvements in Malaysia’s Human Development Index. The HDI measurements include life expectancy at birth, the average and mean years of schooling and GNI per capita. Since 1980, Malaysia’s HDI value has risen from 0.577 to 0.773, and according to the United Nations criteria, 0.8 implies a developed country. This striking improvement in human development alludes to a stronger Malaysia, not just in terms of economic indicators but also in terms of the livelihood and quality of life of its population. At present, less than 3% of Malaysians live in extreme poverty, thus making their goal of eradicating poverty appear much more attainable.

Malaysia’s positive trends in both macroeconomic and human development indicators are very impressive, however, they may not necessarily be enough to reach its goal of developed world status by 2020. The government targets require 6% GDP growth per year, but since 2011, growth has been slightly below that idealistic level. Furthermore, according to the World Bank’s definition, high-income economies are those with a gross national income (GNI) per capita of more than US$12,745, however, Malaysia’s GNI per capita was below this at $10,060 in 2013. The Malaysian economy has recently been hurt by the falling oil prices, as well as a hurting Chinese economy. With these negative externalities facing Malaysia, innovative improvements must be made in order to attain its Vision 2020.

Meanwhile, there may be a dramatic shift in Malaysia’s trade policy. Pragmatic Malaysian policy-makers have maintained an awareness of their reliance on trade, and for these reason have sought to promote its interests internationally by signing the Transpacific Partnership Agreement (TPP). The TPP is an FTA signed by 12 countries Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, United States, Vietnam and Japan: the market includes 793 million people and a combined GDP of 27.5 trillion USD. The intention is to create a seamless market with preferential access to its members. This represents a significant expansion of open market transactions of goods and services between Malaysia and its current free trade partners. More significant is the potential expansion of trade with the United States, Canada, Mexico and Peru; all of whom Malaysia currently has no existing structured frameworks.

Malaysia’s trade-based economy could significantly benefit from access to new markets, global economic integration, and their increased participation in the supply and value-added chains. These economic benefits could translate into the necessary economic stimulus to provide the growth allowing Malaysia to reach its developed status. If Malaysia continues to reinvest these profits into human development, it is likely that a stronger and more sustainable Malaysia can reach its targets. Malaysia is well on its way to attaining its goal through diversification of its trade sectors and partners, which has led to positive trends in terms of education and poverty reduction. There is an optimistic outlook on Malaysia’s trajectory towards success, however, whether it will reach its target by 2020 will have to be seen.

Works Cited:

Australian Government. Malaysia Country Brief. 2015. http://dfat.gov.au/geo/malaysia/Pages/malaysia-country-brief.aspx.

Kok, Cecilia. With 5 Years to go Government Getting Feedback to Achieve Vision 2020. January 15, 2015. http://www.thestar.com.my/Business/Business-News/2015/01/05/A-critical-11MP-With-five-years-to-go-Govt-getting-feedback-to-achieve-Vision-2020-targets/?style=biz.

Macro Economy Meter. Malaysia: GDP Composition Breakdown. 2015. http://mecometer.com/infographic/malaysia/gdp-composition-breakdown/.

Malaysian Investment Development Authority. Manufacturing. 2015. http://www.mida.gov.my/home/manufacturing/posts/.

Ministry of International Trade and Industry. Malaysia’s Free Trade Agreements. 2015. http://fta.miti.gov.my/.

Performance Management & Delivery Unit. Overview of ETP. 2013. http://etp.pemandu.gov.my/About_ETP-@-Overview_of_ETP.aspx.

UN Data. Country Profile: Malaysia. 2015. http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Malaysia.

UN Development Program. Human Development Report 2014. 2015, UNDP

World Bank. Databank. 2015. http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx.