Netflix’s Narcos: America’s Cultural Imperialism Retells History

Make Colombia Great Again

http://bit.ly/2dDR6ZV

Make Colombia Great Again

http://bit.ly/2dDR6ZV

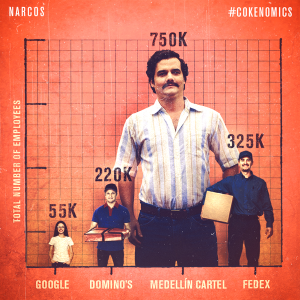

Hollywood holds a monopoly over story telling in Disney movies, HBO specials, and now in Netflix original series such as Narcos. First aired on August 28, 2015 for North American viewers, the series later aired on the American Spanish language network Univision as a “great way to further reach Hispanic audiences and help them discover Netflix.” As if Hispanic viewers were unaware of their own past, Narcos is another example of the U.S. importing violent history for the purpose of entertainment. The engrossing Netflix series “tells the true-life story of the growth and spread of cocaine drug cartels across the globe and attendant efforts of law enforcement to meet them head on in brutal, bloody conflict. It centers around the notorious Colombian cocaine kingpin Pablo Escobar and Steve Murphy, a DEA agent sent to Colombia on a U.S. mission to capture and ultimately kill him.” Hollywood’s typical use of blood, sex, and violence readdresses Colombia’s drug wars just as the nation attempts to push its blood filled memories into the past. After 52 years of war, a historic peace accord between the Colombian government and FARC rebels was signed on September 26, 2016. The deal, which was subject to ratification by Colombian voters in a referendum, was rejected by the people a week later.

The referendum’s confusing aftermath shows a traumatized nation angry over its history, but determined to move forward. Reports show the conflict killed 220,000 people in 55 years, and more than four out of every five victims were civilian non-combatants. The number of Colombians displaced by rebels, paramilitaries, and government security forces is a significant 5.7 million. These statistics are far from entertaining as many Colombian families were brutally torn apart for decades by multiple violent groups.

Hollywood’s interpretation of the Colombian conflict angers many Colombian viewers whose families experienced these “fictional” scenes. The opening quote by famous Colombian writer Gabriel Garcia Marquez, “Magical realism is defined as what happens when a highly detailed, realistic setting is invaded by something too strange to believe. There is a reason magical realism was born in Colombia,” sets a dreamlike tone providing writers with creative liberty to butcher Colombian history in the name of good TV. Even Pablo Escobar’s son shared his negative opinion on the show by distinguishing between what parts are facts and fiction. The U.S. falsely portraying Latin American history to an American audience is another way the U.S. fools its people into believing America to be the benevolent policeman in all foreign affairs. The “War on Drugs” started by the Reagan administration until the W. Bush administration justified U.S. military involvement, depicted in the show by Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) Agent Murphy and his partner who work at the American embassy in Colombia. This ignores the fact that the drug cartel would not be at its height without its American customers. Moreover, the drug war did nothing to stop the drug trade in Latin America, but only made it more violent and displaced it from Peru to Colombia. Choosing the American DEA Agent to narrate the Colombian conflict once again assigns America as the ultimate narrator of history: “This was my war. This was my duty. And I was ready to fight it, and my wife was ready to fight it with me too.”

George Yudice in his essay “La reconfiguración de políticas culturales y mercados culturales en los noventa y el siglo XXI en América Latina” discusses the concept of “cultural maquila,” meaning “production is controlled from abroad, proceeds go to the international conglomerates that own the means of production, and local elements are used in as far as they generate value to a (cultural) product designed for a particular, geographically removed, audience.” In this context, Colombia’s rich cultural history becomes a simplified product marketed toward the American consumer. Colombian culture adds certain “value” to an American product that could only be acquired from a foreign area. Some of Netflix’s profits should be returned to Colombia, as it is their history that Netflix has manipulated for profit.

Hollywood’s false claim of cultural proficiency is a new type of imperialism that treats Colombia’s history as a raw material and the show as the final manufactured product. This is the unchanging tune of America using culture to dominate developing countries, only in a varied, more unrecognizable form. Perfectly summed up, “The cycle of production and consumption is nearly perfect: on the one hand we have the well-known double standard of the United States that allows it to wage a war on foreign soil in the name of the eradication of a product for which they are the largest market; and, on the other hand, the violence generated by this conflict is then turned into a profitable cultural commodity that, like cocaine, encourages an uncritical mode of consumption that ignores the inconvenient truths embedded in it.”

Although the series is undeniably engaging television, Narcos further demonstrates America culturally colonizing Latin America and its history. To the average American viewer, Narcos provides a thrilling background to a party drug he or she took over the weekend at a Frat party. To the Colombian viewer, Narcos exploits personal history in a way that exoticizes and fantasizes trauma. Today’s Colombia is no longer Pablo Escobar’s Colombia, as it has surpassed Peru in becoming the region’s fastest growing economy. Overall, Colombians just “want to feel empowered, not defined by something that happened decades ago.” Who can blame them? This war has tortured Colombian soil for long enough, and with respect towards the country Hollywood should leave its history alone.