Privacy or Surveillance: Switzerland Walks the Line

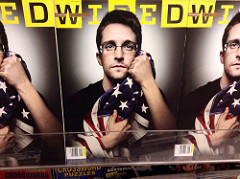

With Edward Snowden giving a talk at McGill on November 2nd, surveillance seems to be a hot topic at McGill. One of the many key problems that Snowden raises with regard to surveillance policies is governments’ lack of transparency when it comes to their gathering of mass-data through surveillance without the consent of its citizens. On September 2016, a referendum concerning the integration of a new surveillance law passed with 65.5% support and is now officially a part of Swiss law. Surveillance is most certainly not a black and white topic, but this new law irrefutably demonstrates Switzerland’s greater respect for transparency and respect for democratic principles. By changing the conversation around surveillance, Switzerland proves that privacy does not have to be excessively breached in order to obtain security through surveillance.

How is Switzerland different to the kind of regimes people like Edward Snowden have criticized? What is most striking about this law is its transparency, as Switzerland’s Federal Intelligence Service will be legally obliged to “inform the subject, within one month about the justification, category, and length of the surveillance”. As a result, the privacy of Swiss citizens can be respected while still allowing for a tightening of security. Secondly, this law was passed democratically and was not done behind closed doors. The Swiss population is therefore aware of what is happening and is not blinded by the actions of the government. Moreover, this law is not about the gathering of mass information; instead, it is merely an attempt at increasing security.

Switzerland’s continuing respect for privacy should come as no surprise, as citizen’s rights are central to the Swiss constitution and the right to privacy is deeply enshrined in Swiss mentality. To a certain extent, the state’s famous bank privacy was partly born out of this desire to protect individuals. The 1934 implementation of banking secrecy (with stiff penalties in the case of a breach) was enacted to prevent employees of Swiss banks from reporting the deposits of German-Jewish citizens in Switzerland.

Of course, it would be an exaggeration to paint Switzerland as a perfect haven of privacy. For much of the twentieth century, most Swiss citizens were convinced that citizens were exempt from surveillance by the authorities unless they were taking part in criminal activities. In 1989, the “Secret files scandal,” as it came to be known, erupted when it was discovered by a Swiss German newspaper that many Swiss citizens had been spied on and recorded by both the police and the military for dozens of years. Over 900,000 Swiss citizens had government files,mostly due to government suspicions of left-wing or pacifist affiliation. This was particularly shocking as Switzerland, a neutral country, ostensibly had no part in the Cold War. Over 300,000 people asked to review their files, only to discover that their affiliation to a pacifist student association had been sufficient to get them tagged and regularly spied on by the government.

Equally shocking was the fact that extreme-right sympathisers had not been nearly as scrutinised as leftist sympathisers, leading some to conclude that the government was not only not neutral, but far-right leaning. As a result of the scandal, strict laws against many forms of surveillance were enacted by the Swiss parliament, making it illegal to open any file on any citizen, except under judicial supervision or for legitimate counterintelligence purposes. Until September of this year, certain activities, like wire-tapping and internet surveillance, were also banned unless approved by the judiciary.

The rise of terrorism over the last few years has posed a serious challenge to the Swiss authorities and counter-terrorism activities. With the attacks in Paris in November 2015, Brussels in March 2016, and Nice in July 2016, Switzerland has seen attacks in cities no less than an hour away by flight. Considering Switzerland’s role in international relations— especially since Geneva hosts the U.N. headquarters, one can understand why people are concerned and therefore the outcome of the referendum.

Whilst the protection of privacy has continued to be a sensitive topic since 1989, many felt it was as important to allow the Swiss anti-terrorism community to have at least the same tools as their Western European counterparts, in particular France and Germany. Guy Parmelin, Switzerland’s Minister of Defense, stated that the passing of the referendum would lead Switzerland to “leaving the basement and coming up to the ground floor by international standards”. The referendum allows Swiss authorities to monitor phone conversations and Internet activity to the same extent as other European states. While this legislation recognizes the growing importance of surveillance in the 21st century, Switzerland’s bid to win its citizens consent through a referendum shows that increased measures must be done with the support of the population. In this way, Switzerland is a prime example of how governments can achieve security without completely compromising privacy.