The Hidden Battle the Democrats are Losing

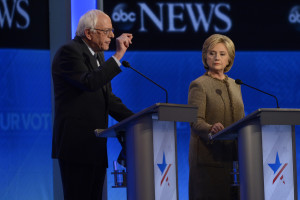

As the 2016 presidential election slowly approaches, more heads turn to pay attention to what is likely the most entertaining political event currently occurring. Things have certainly heated up in recent days as the Democratic primary race has been narrowed down to two candidates. On the Republican side, brazen and unabashedly blunt businessman-turned-politician Donald Trump has seen his dominant position in the national polls suffer a hit with Texas senator Ted Cruz’s victory in the Iowa caucus. Additionally, Senator Marco Rubio has began making major headway as a reasonable alternative to both Cruz and Trump. Sanders’ virtual tie in Iowa and success in the New Hampshire primary notwithstanding, the three current Republican frontrunners present an image of a divided GOP when compared to the comparatively secure position of Hillary Clinton. Indeed, one might argue that it is overwhelmingly likely that Clinton will secure the Democratic nomination and, given her experience and access to resources, she will enter the presidential race against the eventual Republican candidate with an advantage. In short, prospects at the 2016 presidential election look optimistic from the Democratic perspective. Yet there is a very important element of the 2016 election cycle that is being largely ignored that presents a serious problem for the Democratic Party.

Amid the flurry of activity and attention surrounding the primaries for the upcoming presidential election, very little attention has been given to what is arguably a more important branch of US politics: Congress. Come November, elections will be held to fill the 435 seats in the House of Representatives and the 34 seats in the US Senate. Granted, Congressional races are less interesting. They are relevant on a more local level and individuals on one side of the country will rarely care about Congressional races on the other side. However, this does not make them any less important. At present, 247 seats in the House of Representatives are controlled by Republican representatives. This grants the Republican party a majority and effective control of the House; the largest they have enjoyed since 1928. Indeed, barring a miracle on the part of the Democratic party, the House of Representatives will continue to be held by the Republicans after the elections in November. The more pertinent question is whether the Democrats will succeed in gaining control over the Senate. After the wave of Republican victors in 2010, the Senate has been firmly in control of the Republicans. This resulted in Republican control over both houses in Congress. In order to gain a majority, the Democrats will need to win five seats in addition to the ten they currently hold out of the 34 up for election. It is a tough challenge, as very nearly all of the seats currently held by Republicans are either safely Republican or lean Republican, but it not quite impossible.

The question, of course, is why lack of attention to Congressional races is a problem, and more specifically, why it is a problem for the Democratic party. Together, the House of Representatives and the US Senate are tasked with forming and passing legislation. As glamorous and important as the office of President of the United States may be, the one who occupies said position does not have the power to write laws or determine the budget of the United States. This creates a serious problem if a Democratic president fails to enjoy a Democratic majority in either the House or the Senate. Assuming a victory for Sanders, as noble as his ideas may be, it is hard to imagine that a Republican-controlled Congress would agree to implement the policy changes he currently advocates. A Republican Congress would equally pose a problem for Hillary Clinton should she win the general election (a prospect that I would not take for granted). Clinton is notoriously unpopular in GOP ranks and it is unlikely that her campaign promises would be realized in a Republican-controlled Congress. Simply put, in order to push through and realize some of the major campaign promises, a Democratic president would have to either resolve themselves to a term of compromises or secure a Democratic hold over either the House or Senate. This latter option, is highly unlikely due to the reality of Congressional elections in the United States.

A publicly known but infrequently discussed issue in American politics is the reality of Congressional stagnation. It is no secret that Congress (collectively) has notoriously low approval ratings (falling as low as 9% in November 2014 and currently sitting at 16%). This is despite an astoundingly high re-election rate that has only grown in recent decades.[1] Since the 1960’s, the re-election rate of members in the House of Representatives has consistently sat at over 80% and the re-election rate of members of the US Senate has sat at least 70%. These high re-election numbers coincide with comparatively high opinions of individual representatives. When polled, upwards of 50% of responders will respond that they approve of their Congressional representative’s behaviour despite the fact that 60% are unable to name their representative. Numbers are also higher for approval of personal representatives rather than representatives from other districts. This notion of “my representative is not the problem; the others are” suggests that Americans are generally dissatisfied with Congress but lack motivation (or indeed recognition) to enact change.

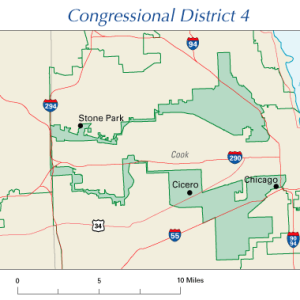

A more empirical explanation for Congressional stagnation suggests gerrymandering (the redrawing of districts to favour a particular candidate or party) is to blame. The theory behind this explanation is that increasingly redrawn districts artificially create “safe” districts where it is nearly impossible for an incumbent to lose.[2] Though popular (to be sure, gerrymandering is a serious problem) there is little evidence or rationality to place the blame for Congressional stagnation solely on gerrymandered districts.[3] A more prevalent theory suggests that overwhelmingly larger incumbent expenditures on campaigns (upwards of 80%) result in very slanted elections where the opposition is left largely unable to compete and thus loses.[4] Congressional races are frankly uncompetitive and heavily favour incumbent officials.

Granted, Republican control of the House is a recent reality as from 1955 to 1995 the House of Representatives was exclusively controlled by the Democrats. A similar story can be said for the Senate; save for a brief interlude from 1981 to 1987, the Senate also enjoyed a Democratic majority. Today’s Republican dominance in Congress may be a product of decades of frustration with Democratic dominance. Furthermore, a bare majority is not sufficient to pass any law the house so pleases. Provided a bill passes through the House and the Senate, the president reserves the power to veto the bill. Only a supermajority (2/3rds of both the House and the Senate) is sufficient to override the veto. That being said, Republican control of both the House and the Senate is still a concern for Democrats who expect to see a Democrat in the White House come 2017 and who hope to see some larger proposed platform issues implemented in the coming years. To make matters worse, provided a Democrat wins the White House, Americans should expect to see Republican control over the House and the Senate grow rather than shrink. A phenomenon known as the “midterm penalty” dictates that whatever party wins the White House will nearly always experience losses in Congress.[5] This is largely attributed to the notion that voters of the losing party (in the presidential election) will have higher turnout during the midterms in order to “punish” the victorious president and balance the power between the Executive and Legislative branches.

In short, as excited as one may be at the coming presidential election, and as excited as one may be at the prospect of a Democratic president, the reality is that the Democratic party is facing a serious problem that is unlikely to be resolved. A Republican controlled House and Senate will cause major headaches for a Democratic president. Without the support of a majority in either House in Congress, a Democratic president will face an uphill battle realizing platform goals and this reality only promises to get worse following the midterm elections. From the Republican perspective, a Democratic president would be a minor setback as current efforts in Congress are proving very successful. A Republican victory (a fair possibility) could potentially give the Republicans unilateral control (at least in theory) of the United States government (if one takes into consideration potential Supreme Court nominations). Republican supporters and the Republican party in general should thus find themselves in a pleasantly comfortable position. However, high levels of Congressional stagnation are a serious cause for concern regardless of to whose advantage it plays. The reality is this: in focusing on the flashy prize, the Democratic Party has set itself up for failure.

Works Cited

[1] David R. Mayhew “Congressional Elections: The Case of the Vanishing Margins,” Polity, 6, No. 3 (1974) 295-97, accessed February 10, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3233931.

[2] Edward R. Tuft, “The Relationship between Seats and Votes in Two-Party Systems.” The American Political Science Review, 67, No. 2 (1973): 549-53, accessed February 10, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1958782.

[3] John A. Ferejohn, “On the Decline of Competition in Congressional Elections.” The American Political Science Review, 71, No. 1 (1977): 167-68, accessed February 10, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1956960.

[4] Michael J. Malbin, Life After Reform: When the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act meets politics (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), 150-51.

[5] Olle Folke and James M. Snyder, “Gubernatorial Midterm Slumps.” American Journal of Political Science, 56, No. 4 (2012): 931-33, accessed February 13, 2016, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23317166.