The Politics of Heritage

http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/images/2014/3/6//20143642549500734_20.jpg

Israeli Police in front of Al Aqsa mosque

http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/images/2014/3/6//20143642549500734_20.jpg

Israeli Police in front of Al Aqsa mosque

With its announcement of a new tram line, connecting West Jerusalem to East, many have accused the Israeli government of using religious and cultural sites in order to further political land claims. The tram line which runs underneath the Al Aqsa mosque is seen by many as a desecration of sacred Muslim soil and an affront to historic Palestinian land claims to the area. The manipulation of a site’s history and physical appearance have long been used by conquerors for centuries to instill their dominance into a conquered people’s psyche. Despite the advent of UNESCO and the Internet, quarrels over these sites continue across the world, as many wily movements, both political and religious, use history as a tool for social gain.

Cultural sites and their history were long a widespread tool of colonial regimes to stamp their cultural superiority on subjugated peoples. The theory of Social Darwinism, which was often used by eugenicists and political elites to portray non-Europeans as inferior, relied on historical and anthropological research, in which historical sites played an integral role. During the colonization of Zimbabwe, the Western discovery of Great Zimbabwe shocked many of the European colonizers. It was impossible in their minds that such a “primitive” and “inferior” people could build such a magnificent stone structure. After the colonization of the area by Cecil Rhodes, the colonizers began an intense effort to find the mysterious origins of these ruins through the establishment of the Ancient Ruins Company. Several archaeologists studied the ruins, and thus concluded that it was built by some great foreign power in a bygone time. These ruins were in fact the creation of the indigenous Shona civilization in the medieval era. Despite empirical evidence of this, the falsified history of the site continued until 1980, when the racist government of Rhodesia was overthrown and replaced with the government of present day Zimbabwe (which is symbolically named after the site). The French faced similar cognitive dissonance when they first encountered the gargantuan ruins of Angkor Wat. Marvelling at its splendour, they concluded it was impossible that the local people they encountered could have constructed it. Instead they created a falsified history of the area, claiming that the ancient

Khmer, a people separate from the modern inhabitants of Cambodia, built it. The creation of such falsified history, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary, was a key tool used by colonizers to undermine the cultural and historical legacy of colonized people, and support their notions of European racial superiority, a key justification used for colonialism.

In India, debates over historical sites also often possess a politicized component. Known to Hindus as the birthplace of Lord Rama, an incarnation of the god Vishnu, the town of Ayodhya has a special place in the hearts of many Hindus. Knowing this, during his conquest of India, the Mughal invader Babur built the Babri mosque on the site, demolishing a much older Hindu temple that had stood there. After the demise of the Mughal empire in the 1800s and subsequent passing of control to the British Raj, Hindus carried on worshiping outside the site of the mosque. With the British leaving and partitioning India (into India and East and West Pakistan) in 1947, religious tensions ran high, culminating in the permanent closing of the mosque in 1949, when religious Hindus started placing statues of their deities at the site.

The debate over who should have access raged on for decades and culminated in 1992, when supporters of the right wing Hindu nationalist BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) and VHP (Vishva Hindu Parishad) stormed an overwhelmed police cordon and demolished the mosque. Widespread communal rioting followed the demolition, with anti-Muslim riots taking place in several major Indian cities and surrounding villages. The Babri mosque has became a key topic of debate in Indian politics, with a politician’s view on the site’s outcome becoming a key indicator of political stance. The current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, has yet to make a comment as to his opinion on the site’s fate. While it may merely be a physical site, the ongoing debate has become representative of the greater schism in India between nationalist and inclusive Hinduism.

Similar to the situation in India, many sites in Israel face religious contention; however, in Israel this comes with the added pressures of territorial and sovereignty-related dispute. Since the destruction of the first Jewish temple by Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar II in 587 B.C.E. , cultural sites have been used as ways of furthering political and religious objectives in the state. In 1967, following the Six Days War against the Arab states, Israel announced plans to destroy the old Moroccan section of Jerusalem. The centuries-old Moorish section of the city lay adjacent to the Western Wall, one of the most sacred sites in Judaism.

Having acquired its ownership of the wall for the first time, the Israeli Jewish government claimed that Palestinian presence in the area would prevent pilgrims from fully expressing themselves, justifying their destruction of a part of the city’s vibrant cultural fabric.

The Israeli government has also used Jewish archaeological claims as cover for takeovers in Palestinian territory. These excavations, illegal under international law, have been used in the past as reason to evict Palestinians from their homes and have in the past caused the collapse of Palestinian homes. The Israel Antiquities Authority has maintained open links with radical settler groups, which see the entirety of Palestine as Jewish Israel by divine right. Criticism of these projects by UNESCO has had little material effect on the ground, with many of them continuing on despite international condemnation. The politicization of heritage in the region was on full display in May of this year, when UNESCO announced its decision to make the old city of Hebron in Palestine a world heritage site. Israel called the decision ludicrous and said it was an attempt at making the Cave of the Patriarchs site (a site holy to both Jews and Muslims) non-Jewish by claiming it as Palestinian, despite the fact that the site is in Palestinian territory. Most recently, following the stabbing deaths of three Jews in Jerusalem at Palestinian hands, Israel said it would ramp up security outside Al Aqsa mosque, making it more difficult for Palestinians to enter (but later dropped the plans amid worldwide pressure). This is once again demonstrative of the way Israel uses its hold over certain cultural sites in the region as pawns in greater games of politics and sovereignty.

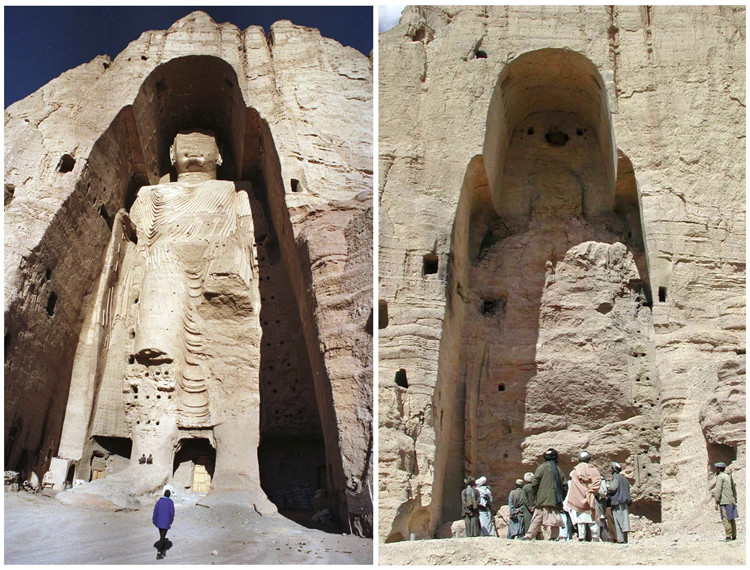

Cultural and religious heritage sites have also been used by many terrorist organizations as tools of mental domination. The destruction of cultural and religious heritage has been a key policy of many Al-Qaeda affiliated organizations in the areas they take over. Carved into the rock face of the Bamiyan valley in the 5th century, the Bamiyan Buddhas stood for 1,700 years, surviving the Islamic Invasions of the 10th century, the Mongol invasions of Genghis Khan and Tamerlane and several attempts at their destruction by subsequent Afghan rulers. After the Taliban takeover of the region in 2001, dynamite was drilled into their rock face and blown up, despite widespread pleas from the international community.

Aside from the fact that the Buddhas were against the Taliban’s extremist Muslim ideology forbidding physical depiction of gods, many speculated that this was a tool of intimidation by the Sunni Muslim Taliban against the Shia Muslim Hazara people of the Bamiyan valley. The Hazara people had a deep connection with the Buddhas, as their pre-Islamic ancestors had built the Buddhas and they had been stewards of their preservation for centuries.

Sunni Muslim ISIS used similar policies of mental domination against religious minority groups during their takeovers of Timbuktu and Mosul. Almost half of Timbuktu’s world famous shrines to various Sufi saints were destroyed after ISIS’s takeover of the city, a huge blow to Mali’s cultural heritage. After their takeover of Mosul, ISIS proceeded to destroy any mosques, churches and shrines which were not in keeping with their type of extreme Islam. This included the ancient mosque to the prophet Yunus (or Jonah), in which his remains were believed to be kept, reduced to rubble by ISIS after having stood for hundreds of years. Even non-religious sites have been the victim of ISIS’s destruction, with the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra facing destruction at their hands as well as several ancient Assyrian cities. These organizations’ destruction of anything historical that does not fit their ideology, surfaces a pervasive agenda to not only prevent people in the present from following beliefs which do not align with theirs, but to destroy any evidence that people in the past ever did.

While the politicization and occasional destruction of heritage may seem like innocuous acts, one without victims, they are in fact crimes against humanity, striking at the very mettle of human existence. Heritage sites are the physical manifestation of our history, and with their destruction and manipulation comes the perversion of history to fit modern agendas. Whether it is ISIS destroying Palmyra to erase any trace of non-Islamic history in Syria or Rhodesia’s rewriting of history to make Great Zimbabwe a Greek creation rather than an African one, the manipulation of history has effects on current reality and as has been shown in the past to have effects on the future, as well.