A Look Into Aboriginal Culture in Montreal

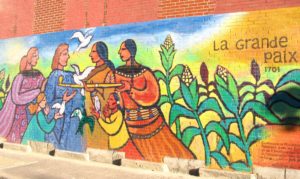

Montreal street art exhibiting "The Great Peace of Montreal" signed in 1701 between New France and First Nations.

Montreal street art exhibiting "The Great Peace of Montreal" signed in 1701 between New France and First Nations.

Declared in 2009, National Aboriginal Month celebrates Indigenous populations across Canada by commemorating their traditions and cultural heritage. More than a celebration, it has also opened up much-needed discussion and reflection on the treatment of First Nation, Métis, and Inuit communities in Canada. To celebrate the Aboriginal population, I want to take a closer look at what it means to be Indigenous in Montreal.

Every year, Montreal observes a constant increase in its Aboriginal population. Although fairly recent, anthropological research on urban policy and Aboriginal peoples suggests many leave their reserves in search of better living conditions and employment opportunities. However, hardly any literature has looked at how their culture is thriving in an urban context and how cities have adapted to welcome this new influx. In this article, I am especially interested in questioning whether Aboriginal culture has found its place in Montreal and, if not, what has hindered that development.

On May 17th, Montreal’s mayor, Denis Coderre, celebrated our city’s 375th anniversary. While his speech praised Montreal’s growing diversity and multiculturalism, Coderre paid particular attention to the Indigenous population living in the city. He repeatedly reminded his audience that Montreal’s greatest asset was its ability to continuously “put forward the idea of living together.” Similarly, Coderre hoped Montreal’s anniversary celebrations could serve as a base for reconciliation between Indigenous people and the Canadian government.

If this narrative does not sound totally unfamiliar to you, it is because it is not. Over the years many politicians have played with the notions of inclusion and reconciliation as a way to forward their relationship with Indigenous people. You may even remember a year ago, Denis Coderre using a similar discourse when coining Montreal as “the city of reconciliation.” The question then arises: why is Coderre using the same discourse? Has really nothing changed in a year?

This is obviously a very difficult question to answer. On one hand, you could say there have been some changes –or even some improvements– concerning the inclusivity of Indigenous populations in Canadian politics. Just this month, in fact, Marc Miller, a Liberal Member of Parliament from downtown Montreal, delivered a statement in the House of Commons in Mohawk. He hoped that with this small action he would not only honor the Mohawk language and its speakers but more importantly encourage other members to learn this complex language. For Miller, this would be a decisive step towards improved communication and eventually stronger relations with the Aboriginal population in Canada.

While this story offers Denis Coderre a glimpse of a brighter future, he still has a way to go before his speeches addressing the Indigenous population in Montreal are no longer dominated with notions of reconciliation and pleads for inclusivity. In fact, it is safe to say little has really changed in a year. The Indigenous are still struggling to make their voices heard. The inquiry into Quebec’s treatment of Indigenous people only began last month and has already exposed the cracks of the immense lack of social inclusion amongst Quebec’s public institutions. Many testimonies stressed the importance of listening to those who have been silenced and insisted upon the fact that this was the first step to take towards a successful reconciliation.

Both narratives showcase precisely why Denis Coderre has not progressed in the past year. On one hand, Canadian politicians like Marc Miller are actively attempting to improve communication and construct an environment that allows Indigenous populations to coexist in Canadian society. On the other hand, Quebec’s inquiry has exposed a complete exclusion of Indigenous communities and absence of fruitful communication. Back to back, these two examples clearly showcase a clear discrepancy between the actions of members of the Canadian government and what they have actually achieved for Aboriginal people. Although I do acknowledge the amplitude of this conflict, I want to offer another reason why Canadian politicians, including Denis Coderre, still struggle to understand Aboriginal culture and meet the needs of its practitioners.

George Wenzel is a professor who has investigated why we struggle to understand and respond appropriately to cultures we cohabit with. In his piece The Culture of Subsistence, Wenzel tackles one of the most popular misconceptions of Inuit culture: their primitive and simplistic values. He points out that Indigenous communities are often portrayed as one-dimensional societies composed of hunters that live in the North, isolated from any form of modernity. This popular image fascinates the western public the most and has thus come to dominate our preconceptions. Wenzel explains that this fascination stems from the fact that the Indigenous seem to represent the antithesis of modernity, a society so environmentally and materially distant from our own.

Absent from this understanding of Indigenous communities is the recognition that their culture is more than dog teams and harpoons. Therefore, when contemporary Indigenous lifestyles are presented as having both adopted modern tools and adapted to present-day practices, they are pushed aside and deemed illegitimate or less traditional. As George Wenzel notes, what’s interesting here is that we have nurtured an image of a community purely based on their materialistic habits, leaving aside the very foundations of any society, this being their values, beliefs, and behaviours.

I found Wenzel’s theory not only insightful but also very useful when thinking about Indigenous communities in cities. Even though we now rarely perceive Indigenous lifestyles as being composed purely of “dog teams and harpoons,” we know so little about their practices in an urban context and the extent of their inclusivity in cities like Montreal. I believe this is because we have failed to modify our one-dimensional perspective, leading us to perceive their community as existing on a separate tangent than the rest of Canada’s population. By only acknowledging one facet of traditional Indigenous livelihoods, we not only remain ignorant but also unable to properly address their culture.

This is particularly problematic for Indigenous populations in Montreal for several reasons. To begin, once Indigenous communities are placed in an environment deemed less traditional than those of western ideals, it is concluded that they no longer retain their cultural traditions. This makes it particularly difficult for Indigenous communities living in urban spaces to practice their culture and beliefs. Cities such as Montreal have not accommodated to these practices, providing Indigenous culture with barely any platforms to thrive amongst Canadian cities.

In a report written by Nobuhiro Kishigami on Inuit social networks in cities, the Inuit claim to live scattered across the city as opposed to in close ties with their community. As a result, they lose their close kinship ties and are unable to speak their traditional languages or enjoy northern food. This lack of opportunities to engage in Aboriginal practices has also meant that they tend to lose their cultural identity. This is especially true for young Indigenous children who were born in Canadian cities and were deprived of opportunities to engage with their Indigenous identity.

Finally, a misunderstanding of Indigenous culture also means Denis Coderre is not getting any closer to meeting the needs of Montreal’s Indigenous population. Evidently, their unusually high rates of unemployment and substance abuse cannot be explained by a simple misperception of their culture and are not entirely caused by a complete neglect from the Canadian government. However, the lack of voice and the invisibility felt amongst Indigenous, which prevent them from engaging with the rest of the world, can be remedied with a deeper understanding of our presumptions and the presence of their culture in contemporary Canadian society.

Overall, my viewpoint on the issues Indigenous face upon moving to cities and more generally in Canada is in no way complete. There are many aspects of Indigenous livelihoods in Canada, which are equally as meaningful, that I regrettably could not touch upon in this article. However, here, I wanted to offer a perspective I found rarely discussed in Indigenous literature and research. Indigenous communities are increasingly migrating to southern cities and, while mayors like Denis Coderre attempt to reach out to all members of his population, urban settings continue to generate an environment which does not favour a lively practice of Indigenous culture.