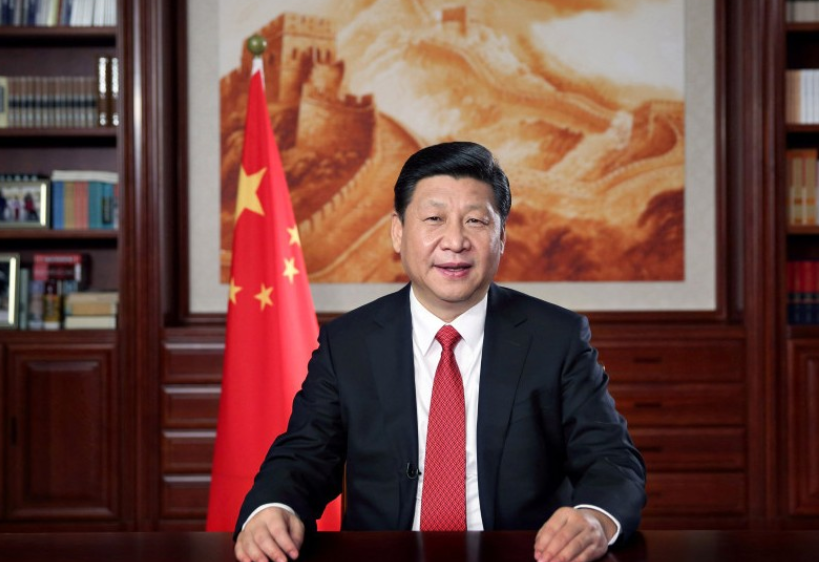

The 19th Communist Party Congress: A Test for Xi Jinping

In mid-October, about 2,300 delegates will gather in Beijing for the 19th Party Congress. Held every 5 years, the Party Congress has three main functions. The first one is to set broad policy guidelines and agenda for the next five years. The second one is to “revise the Party’s Constitution”- adjustments in ideological formulations or recruitment criteria. The third one is to change the composition of the top leadership and decision-making bodies of the PRC. Importantly, this Party Congress will give clues as to how effectively Xi Jinping has consolidated his power since he took office and how he wants to move forward with it.

Indeed, many analysts have argued that the first term would be spent accumulating power and imposing party discipline, which would then be wielded during his second term to influence politics and implement reforms. As this gathering marks Xi’s entry in his second term, many will look at the composition of the Central Committee, the Politburo and its Standing Committee, to assess the extent of Xi’s grip on power. This accumulation of power responds to looming economic difficulties inherent to the development of the Chinese economy and to the way the CCP interlinks with the economic system. In order to maintain stability, these tough but much-needed economic reforms are being counterbalanced by Xi’s international projects and a domestic ideological vise.

China is at a key turning point in time, as its economy must transition from an export-driven growth model to demand-led development. Undoubtedly, this economic rebalancing will be painful. Debt overhang, industrial overcapacity, SOE restructuring but also capital deepening, and the creation of a social safety net are all issues that need to be addressed. But China has a very complex political economy, manifested by entrenched interest groups. Party discipline is a prerequisite for reforms. However, unlike SOE restructuring, that often involves layoffs, anti-corruption measures within the CCP and the PLA are popular among Chinese people.

Beyond party discipline, China also needs strong and powerful leaders willing to implement necessary but painful economic reforms. According to Michael Pettis, “unless power is concentrated even more, Beijing cannot force the necessary transfers of wealth from ‘vested interests’ to ordinary households”. Up until now, resources were transferred to local provincial elites for investments, but now that domestic consumption has become a priority, these resources should go to ordinary households. At the 18th Party Congress in 2012, “the party leadership believed that a strong party center was best positioned to cut through vested interests and push through tough reforms” argues Matthias Stepan.

Over the past few years, numerous prominent political leaders have been promoted for their governing experience in hardship regions like Tibet, Xinjiang or Guizhou. The Brookings Institution puts forward two arguments to explain the elevation of these leaders. Firstly, “Xi is using their experience to justify quicker promotions for his protégés since the CCP establishment privileges experience in China’s frontier region”. Secondly, their expertise in those regions “enables Xi to place an even greater emphasis on the governance and development of China’s western and southwestern frontiers”. These arguments are also helpful to understand Xi’s political visions. If “hardship makes better leaders”, then Xi has formed a narrow team of decision-makers able to endure pain and act quickly.

In fragile economic times, maintaining political stability is crucial for the CCP. The Belt and Road Initiative, which aims at building infrastructures along land and sea trade routes from China to Europe and Africa, has economic and political motives for China. Economically, China seeks to export its industrial overcapacity and develop the neighbouring countries and its remote provinces like the Xinjiang. It expects in return, that economic development will stabilize and pacify the region in the hope of diminishing the terrorist threat in the country. In parallel, an aggressive foreign policy in the South China Sea ties the people together around nationalistic sentiments.

Moreover, Xi reasserted civilian command over the PLA, cleaned up the house from corruption, restructured and modernized it toward a more efficient “Western-style joint command” system. This transformation of the Chinese military needs to be contextualized. China is becoming a major regional security player, not to mention the security concerns that underlie the One Belt One Road Initiative and those that will come with it. A more professional, mobile and coordinated Chinese military will probably be needed to intervene on different fronts at the same time.

During his first term, Xi declared that his mission was to accomplish the “Chinese dream”, defined as the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. The CCP has since been promoting, in schools and universities, its own interpretation of Confucianism and Chinese traditional culture. Control on the media and Internet censorship has increased to limit the impact of western influence. Resorting to the distinction of national characteristics enables Xi to present a “Chinese model” in opposition to western democracies. Some analysts even suggest the mention of “Xi’s contribution to Communist ideology”, a continuation of the elevation to the status of “core leader” last year. In fact, the establishment of an ideological doctrine – a “Xi Jinping Thought” that only compares to “Mao Zedong Thought” – can be interpreted as a bid from the CCP to regain legitimacy lost in the domestic economic and social turbulence that run across China. Pulling the ideological strings hence allows the Chinese ruling elite to maintain social and political stability.

The size and complexity of the Chinese political economy make policy-making a very difficult task, and where vested interests constitute rigidities. The ruling elite must be very powerful and endure pain to reform the country. Xi’s consolidation of power thus responds to these political necessities. Nonetheless, the pain associated with these economic reforms can’t undermine the political stability of the country. Externally, this translates into the Belt and Road Initiative destined, among other things, at putting China back on its historical place in the world. Internally, this translates into the need to build an ideological doctrine that sets a vision and ensures harmony. About Xi, Robert Lawrence Kuhn finds that “a core leader must fit the times and the status must be earned”. It is certainly what Xi is attempting to do.

Edited by Pauline Werner