2017 G-20 Summit: A New Order

G-20 leaders at the summit in Hamburg.

https://flic.kr/p/WAUn1x

G-20 leaders at the summit in Hamburg.

https://flic.kr/p/WAUn1x

https://flic.kr/p/WAUn1x

On July 7th and 8th, the annual G-20 summit was held in Hamburg, Germany. Amid the discussion, expectedly centred on global trade and the environment, what came as a surprise was its level of debate and need for compromise. The media coverage, though not necessarily more extensive than previous years, was significantly more exciting: from Trump meeting Putin for the first time since assuming office to protests which quickly turned violent.

These divergences are only examples of what this year’s summit was truly about: the G-20 is changing. Established in 1999, the Group of 20 is comprised of 19 member states and the European Union (EU) which make up 85% of world’s GDP and account for two-thirds of its population. Unlike the G8, now functioning as the G7, which “seeks cooperation on economic issues facing the major industrial economies,” the G20 represents these industrial economies as well as emerging ones.

Over the years, the assumption was that the G20 would facilitate convergence of major powers into a “single model of liberal international order” through trade and cooperation. Since an inaugural meeting between G20 leaders, and not just their finance ministers, took place in Washington DC in 2008, these annual summits have allowed these leaders to progress on this convergence face-to-face, all together. While decisions made by the G20 depend on the dedication of individual countries, the opportunity to discuss and potentially influence other heads of states on certain economic policies is certainly attractive.

Though this time around global trade and the environment were at the centre of the talks, the majority of the Hamburg summit seemed to be about divergence. Debates dominated the meetings and the necessity for compromise met an all-time high: this ‘single model of liberal international order’ seemed forgotten.

The debate on trade is not solely due to recent protectionist policies like those of Trump: the world is quite different since annual summits began 18 years ago. Events such as the war in Iraq, 2008 financial crisis, the Arab Spring, the continued conflict in Syria, Brexit, and the recent U.S. election have had a profound effect on what may very well be the ‘end of convergence’ in the G20.

In light of these latter two, very difficult talks on trade dominated summit discussions. While some European countries and China proposed stronger support for free trade and “cooperative multi-country frameworks for trade” like the World Trade Organization, they had to contend with the US’ new but firm stance against globalization.

The result was a vague statement made on Saturday by finance ministers which stated that countries “are working to strengthen the contribution of trade” to their economies. The statement, though joint, does not distract from the inevitable fighting which led to its vagueness: “Maybe one or the other important member state needs to get a sense of how international co-operation works” said Wolfgang Schaeuble, Germany’s finance minister, omitting any names. “It’s completely clear we are not for protectionism,” Schaeuble continues. “But it wasn’t clear what one or another meant by that.” His stance was unclear.

The other chief subject among discussion at the summit was the environment and the Paris Peace Agreement. Its fate was called into question on June 1st when President Trump announced that he would pull the United States out of the Accord. Since then, there has been much debate over whether other leaders would abandon the 2015 climate accord, most of which can be put to rest following the G20 summit. In the summit’s final communique, the other 19 members held their ground, stating that “the Paris Agreement is irreversible… We reaffirm our strong commitment to the Paris Agreement, moving swiftly towards its full implementation.”

As a result, the US was left separate from the pack as the only G20 member to not support the Paris Accord. Over the weekend this became a theme for President Trump, whose ‘America First’ approach to the summit left him seemingly isolated. This approach not only put the rest of the G20 on the defensive, says Eswar Prasad, a Professor of Economics and Trade at Cornell University, but also “comes at a cost of eroding US leadership.” Unlike previous summits, where the US had a leading role, Hamburg produced a vacuum filled by the likes of German Chancellor Angela Merkel, new French President Emmanuel Macron, and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Despite a different role at the summit, media coverage significantly focused on the US President and his actions. One such focus was his first official meeting as President with Russia’s Vladimir Putin. The July 7th meeting caused a stir as President Trump confronted Putin about Russian involvement in the 2016 US federal election, which he curtly denied, and as the two agreed on a ceasefire in southern Syria. In between this meeting, with Trump’s continuous stream of compliments to fellow world leaders and opting out of a traditional final press conference, those expecting the confident leadership of his predecessors were left wanting.

https://flic.kr/p/Wc6vZY

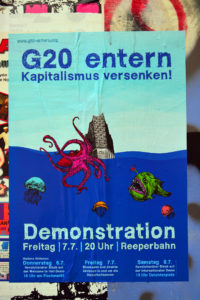

In contrast, the protests which rocked Hamburg Thursday through Saturday were far more than what authorities and even Angela Merkel herself bargained. While Hamburg is known as a place of leftist activism and some protests and public dissent were expected, some protests quickly degenerated into looting and arson met with water cannons and tear gas. Not all protests ended this way: some, such as one by a German performance collective involving volunteers dressed as zombies and painted grey marching through the city, remained the civil disobedience expected in response to the summit. Instead of exhibiting the strength of German democracy in face of public criticism and civil disobedience Merkel condemned the violence in Hamburg, but before this, protesters made clear that a significant amount of people disagree with what they consider the ‘system’ perpetuated by the G20 : inequality, embedded racism and sexism, environmental degradation, and high costs, among others.

Much can also be said for what did not occur in Hamburg last weekend: no comments were made or joint statement given on North Korea’s increased belligerence in recent weeks. Despite some members’ protests that the G20 should not discuss security matters, the group lost an opportunity on how to deal with the increased threat in a cohesive manner. The lack of vagueness surrounding the ‘no support for protectionism’ statement does not clarify what policies the G20 does support: in fact, this stance seems open to individual countries’ interpretations.

So while on the surface it seems to be the ‘G-19 plus one’, penned by Chris Uhlmann of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, this is a false representation: these 19 members are just as divided. Members may still pursue individual agendas, but now they do so without a natural alignment. The G20 may have removed the environment from the backburner, but they may have placed its previous order in its stead.