44 States, 86 Houses, 5923 Legislators, And Almost Zero Attention: This November’s U.S State-Level Elections

Republicans have only fielded enough candidates to fill one in three of these seats. Which isn't altogether surprising, since this is Massachusetts.

Republicans have only fielded enough candidates to fill one in three of these seats. Which isn't altogether surprising, since this is Massachusetts.

Those political junkies like me anxious to see if America is marginally closer to a Trumpocalypse might find themselves hastily clicking “Refresh“ on the FiveThirtyEight election model, or the New York Times’. Those of us curious to see if the eventual President can actually accomplish anything might go to these same websites’ Senate models and click through a few key races.

Then occasionally, a news organization would remind us that there are House elections too! Although those are generally less exciting; a continued Republican majority is all but assured, due to the size of their current majority and the favourable district map (due partially to gerrymandering, but also just to natural geography).

But slipping under the radar are 5,923 state legislative seats up for election across 44 of the 50 states, and these are arguably as important than the ones mentioned above – the federal government is likely to be mired in dysfunction and gridlock for the foreseeable future, but a great deal of significant legislation continues to be passed at the state level.

In the last six years since the wave election of 2010 (during which time the Republicans have gained 910 state seats out of about 7,300 total, essentially as midterm backlashes against President Obama), 31 states have enacted legislation making abortion less accessible, 20 have passed tighter requirements for voting, 20 have rejected the Medicaid expansion portion of the Affordable Care Act, 15 have cut back on unions’ collective bargaining rights, and 27 have loosened gun restrictions, in addition to movement on the usual issues of taxing and spending. Republicans’ dominance at the state level also allowed them, after 2010, to draw Congressional (as well as state legislative) maps as they wished, contributing to the noncompetitive House we see today. Yet, despite these elections being so clearly consequential, they tend to stay out of headlines, especially compared to the daily presidential and senatorial horse-race coverage.

One reason for that might be that the issues are sometimes personalized in the governor (who, unlike in Canada, is elected separately from the legislature). Kansas’ series of mammoth tax and spending cuts are generally ascribed to Sam Brownback personally, while North Carolina governor Pat McCrory (who is in a tough re-election fight this year) is criticized for his “acquiescence to a strongly conservative agenda passed by the GOP-controlled legislature“, most notoriously the transphobic “bathroom bill“. But it’s the Republican legislature responsible for proposing and passing that legislation that should really be put up to scrutiny this election cycle, not just the man who signed it – even if McCrory’s Democratic challenger wins, he can’t repeal the legislation on his own. Yet, even as the governor’s race has become genuinely close and interesting, the state legislature, in a race where only half of the House seats feature two major-party candidates, is more likely than not to remain in Republican hands.

“Close and interesting” are, indeed the two last words one could use to describe state legislative elections in general. There may technically be 5,923 races, but only 58% of them are actually contested, i.e. feature candidates from both the Democrats and Republicans. (And unlike in Canada, every state, from true-blue Massachusetts to deep-red Wyoming, has only those two main parties.) Add to that the facts that over 80% of seats feature an incumbent and that over 90% of them win (only 20% of them even face a primary challenge) – and a picture emerges of a profoundly noncompetitive set of elections at the state level. This is pretty problematic from a philosophical point of view, in the sense that democracies give voters ultimate power, through their ability to scrutinize representatives’ actions and to decide whether to keep them or not. At the point where a majority of races aren’t remotely competitive, and a significant proportion of Americans don’t even have the choice of a different candidate to vote for – how democratic are the states, really?

Those who do pay attention to state elections say that Democrats have the opportunity to pick up ten to eighteen chambers (out of 86 contested this year – there are 99 total, two per each state except Nebraska), while Republicans can set their sights on between seven and nine chambers. This might perhaps sound like a lot. But these aren’t seats within a broader chamber that one can pick and choose and add together; these are each autonomous, powerful legislative bodies that have the power to shape millions of lives each. That about sixty of them should just be treated as foregone conclusions should feel problematic – it’s hard to imagine elections to provincial legislatures in Canada being written off and ignored in a similar manner. This is, however, a general pattern across American state elections – 45 of the 99 state houses have been controlled by the same party since the turn of the century, including both houses in 16 states. In comparison, every Canadian provincial legislature has flipped at least once since 2001 (though, in fairness, there have historically been a few decades-long dynasties).

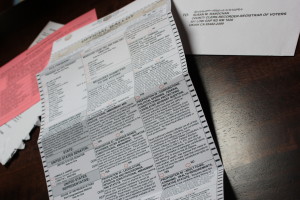

President, U.S. Congressperson, U.S. Senator, governor, state assembly person, and state senator aren’t the only positions that various states have on the ballot November 8th. There are also county, municipal, and judicial elections (including an Arizona race that could throw out notoriously racist sheriff Joe Arpaio), and numerous ballot initiatives: five states are considering legalizing recreational marijuana, four are considering increasing the minimum wage, while others are entering uncharted territory – Colorado is putting a single-payer health care plan to a referendum, while Washington is doing the same with a state-wide carbon tax. Finally, in truly excellent news for politics junkies, Maine is considering adopting preferential voting (they call it “ranked-choice voting”) for all state and federal elections – with any luck, abandoning first-past-the-post could foster the rise multiple parties and thus alleviate the noncompetitive problem I mentioned earlier.

All these issues make for some astonishingly thick ballots, and it’s perfectly understandable that the parties, the media, and voters need to prioritize certain elections over others. However, if some of the collective national attention were diverted to the states, if for each chamber up for election the record of the incumbent and ideas of the opposition were discussed to the extent they are in Canada – that should go some way in improving the quality of American democracy.