Bolivarian Gatekeepers: the Road to Military Praetorianism

Former president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez with the National Armed Forces.

Credits: Archives

Former president of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez with the National Armed Forces.

Credits: Archives

Hugo Chávez was able to galvanize support and loyalty among the peasants during his tenure as president of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela through the implementation of what he referred to as “twenty-first century socialism.”

Credits: Archives

Quiescence was maintained via generous social spending policies, facilitated by the favourable price of crude oil from 2005 onwards. However, what Chávez understood to be crucial in consolidating political power was the quintessentially Machiavellian principle of “keeping one’s friends close but enemies closer”. In his magnum opus The Prince, Nicholas Machiavelli recounts how Cesare Borgia defeated the Orsini and Colonna families and won their allies over by bestowing upon them titles in government, as well as high appointments in his armies.[1]

Mirroring Borgia, Chávez realized that the National Armed Forces would require a combination of both repression and largesse after his temporary ousting by the military in 2002. Accordingly, shortly after returning to power, El Comandante’s surgical procedure involved gutting the leadership of his Bolivarian army. The president dismissed and replaced the commander of the military academy and the chief of the armed forces’ command, as well as 106 of the 206 generals and admirals who either backed his momentary overthrow or failed to support him[2]. What Chávez—a cunning and enthralling former colonel—initially gripped with severity, he countered with magnanimity. In 2004, a benefits plan was announced that would effectively increase the annual salary of the armed forces by approximately 45%[3]. Additionally, retired or active military officials controlled roughly 32% of cabinet positions the year his popularity reached its nadir. In 2011, he followed suit with another 50% salary increase for soldiers in the National Armed Forces in the midst of a national recession[4]. Starting in 2013, shortly after Maduro’s narrow victory over Henrique Capriles in the presidential elections, it appeared undeniable that the newly vested president had taken note of his predecessor’s machinations.

Credits: Ultimas Noticias

Venezuela’s current political and economic landscape paint a bleak picture. Already wrought by triple-digit inflation that has effectively left more than 70% of the populace in poverty, the IMF projects a further 2200% rise in inflation in 2017.[5] This, combined with the paralysis of the legislative branch, crumbling infrastructure, and a rising homicide rate, has exacerbated societal upheaval in the Venezuelan polity.

According to Datanálisis, 80% of Venezuelans demand that the incumbent President and heir to Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution, Nicolás Maduro, leave office this year.[6] The figure is at odds with the image of revolution portrayed by the late Chávez—a grassroots movement for and by the people. Adding to the ostensible woes pointing to the moribund state of Chavismo, the MUD (Mesa de Unidad Democrática) opposition garnered a surprising victory in the December 6th legislative elections—effectively obtaining simple-majority control of the national assembly.

To the casual observer, the ousting of Maduro and the PSUV (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela) seems to be a formality. However, the inextricable link between the government and the Venezuelan National Armed Forces must also be considered. When Hugo Chávez took public office, the roots of his personal ideology—Chavismo—were entrenched through article 236 of El Comandante’s sacrosanct Bolivarian Constitution, which effectively placed the appointment and demotion of any officers ranked as colonels or naval captains and above under the discretion of the president.[7]

The 1999 constitution thus marked a turning point in the military’s role in government. Though they were previously secular and civilian, the National Armed Forces were to become moulded to the liking of the ruling president. What has subsequently transpired, according to Dr. Cynthia Arnson of the Wilson Centre, is the systematic purging of dissenting voices within the military, which intensified after the opposition’s unsuccessful coup in 2002.[8]

However, besides allowing the president to dispose of officers at his discretion, the constitution also enabled active and retired officers to occupy government positions formerly reserved for civilians. This blurred the lines between the government and the National Armed Forces. With his new constitution, Chávez opened Pandora’s Box—inching the Venezuelan polity closer to the seed of praetorianism that has gradually rooted itself into the fabric of domestic politics.

In present-day Venezuela, roughly 50% of state governors as well as 33% of cabinet ministers are active or retired military officers.[9] Additionally, current or former members of the armed forces have gained control of the most important ministries – internal relations, justice and peace, finance and public banking, and defence – wielding an incredible amount of political clout and power.

Credits: European Press Agency

Notwithstanding their attested presence within government, the National Armed Forces’ exertion of cabinet control merely represents

the tip of the iceberg. Earlier this year, Maduro issued a decree allowing the creation of a military-owned company—CAMIMPEG—which placed the extraction of oil under the jurisdiction of the NAF, and more precisely under the hands of Minister of Defence and Major General Vladimir Padrino López. With petrol accounting for Venezuela’s main source of income, the decree extended the National Armed Forces’ influence to the economy. Moreover, since the 2013 presidential election, the Venezuelan military has overseen the creation of its own bank—the only military-owned one outside of Vietnam and Iran.[10]

According to Victor Mijares of the German Institute of Global and Regional Studies, there’s reason to believe Maduro “seeks to ensure the loyalty of the military” not only by granting them the monopoly of violence, but also a considerable stake in profits reaped by the extraction and sale of natural resources.[11] It appears evident that the Venezuelan economy has undergone a gradual militarization. As much as the NAF had proven to be a boon for Chávez—a former military officer himself who was revered by the National Armed Forces—they may be a bane for Maduro who, according to retired general and former Chavista Antonio Rivero, “does not have the leadership” among the military that Chávez enjoyed.[12]

That Maduro’s presidency has not inspired wide respect among the armed forces can be epitomized by the problematic fact that more generals have been promoted during Maduro’s last two years in power than in Chávez’s last five years. The noted increase in military preferment is merely symptomatic of the president’s desperation for loyalty from an institution with ever-growing incentives to distance itself from the regime in a gamble to preserve its dominance within the government. Patronage has bought Maduro precious time while the miscellaneous factions within the National Armed Forces struggle to achieve a harmony of interests. Additionally, in 2015, when Venezuela was wrought by crippling hyper-inflation, the plummeting price of oil, and chronic food shortages, the Bolivarian Republic was Latin America’s top buyer of weapons according to the Stockholm Institute of Peace Investigations.[13] The fact that funds were being allocated to such unwarranted military expenditure when the country faced a $28 billion USD deficit[14] speaks to the quintessentially Latin American paradigm of power that Venezuela embodies. Chavismo and Madurismo, as much as they purportedly aimed to represent vehement rebuttals to political elitism, nevertheless embody its fundamental elements—corporatism and clientelism.

The government, incontrovertibly, wants to remain in power. With abysmal public approval ratings, however, Maduro and the PSUV must cling harder to the NAF for any hope of salvaging the moribund aspirations of Chávez. The military faces an equally daunting

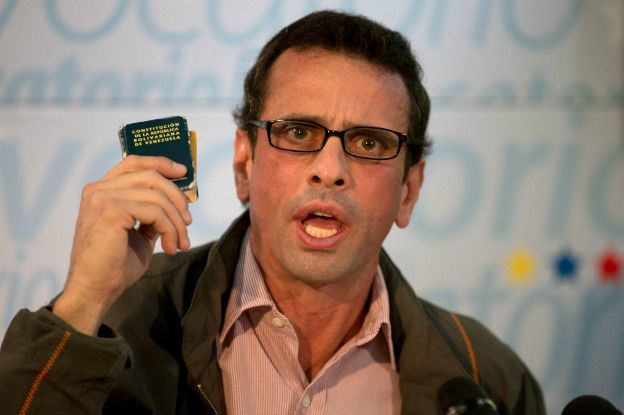

dilemma. At the end of May, the leader of the opposition, Henrique Capriles, exhorted the armed forces to “decide whether [they’re] with the constitution or Maduro.”[15] As much as the NAF may perceive themselves to be an indomitably entrenched force in domestic political decisions, they are not completely impervious to political relegation.

The military has been accused by the opposition and Human Rights Watch of violently suppressing peaceful protests with impunity.[16] Hence, it seems plausible that the armed forces may at one point become more disposed to cooperate with the opposition in expediting the ouster of Maduro when his political survival appears no longer viable in order to evade accountability. What seems unlikely, however, is a complete tabula rasa of the Bolivarian entrapments embedded by Chávez. The National Armed Forces’ influence has transcended areas traditionally controlled by civilians, and the military’s popularity, historically has been the highest among state institutions throughout Latin America.[17]

That Maduro has managed to retain control of power this long is a matter of political clientelism. Now, with less resources and mounting international pressure, the final hour appears to be looming. Whether executive control is usurped from Nicolás Maduro swiftly by putsch, or slowly by the opposition’s efforts to issue a recall referendum before January 10th, 2017—the deadline to oust the incumbent president and expedite new elections—the National Armed Forces plainly possess too much political and economic capital to be extricated from legislative and economic dominion.

In January 1958, the National Armed Forces overthrew President Marco Pérez Jiménez. A civilian-elected government brought an end to military rule by the end of that year. In 2016, the president is hanging by a thread while the PSUV’s political survival is all but certain. Meanwhile, the praetorian seed planted by Chávez has metamorphosed the armed forces into a brick wall among a crumbling edifice—the only element of stability in a country afflicted by volatility. The caudillo culture is indeed alive and well. In a country on the brink of upheaval, the opposition will have to work in concert with the beasts of the Bolivarian revolution if Venezuela is to have any hope at removing the ubiquity of praetorianism and reversing the developmental backwardness that has plagued the polity once considered an example of democratic stability in Latin America.

[1] Machiavelli, Nicholas (1515). The Prince. Page 30.

[2] Tamayo. Juan. “Chávez Purging Military After Coup”. The Miami Herald. N.p., 19 May 2002. Web. 10 August 2016

[3] “Venezuela: Presidential Loyalty and Army Restructuring”. Stratfor. N.p., 3 February 2004. Web. 10 August 2016

[4] “Chávez anuncia incremento de 50% en sueldo del sector militar”. El Universal. N.p., 26 October 2011. Web. 10 August 2010

[5] Moisés, Naím & Toro, Francisco. “Venezuela Is Falling Apart: Scenes from daily life in the failing state”. The Atlantic. N.p.,12 May 2016. Web. 26 July 2016

[6] Lozano, Daniel. “El 80% De Los Venezolanos Quiere Que Nicolás Maduro Deje El Poder”. El Mundo. N.p., 4 July 2016. Web. 26 July 2016

[7] “Constitution Of The Bolivarian Republic Of Venezuela” (1999). National Constituent Assembly

[8] Thomson, Jason. “Amid crisis, Venezuelan opposition tells Army: make your choice”. The Christian Science Monitor.N.p., 18 May 2016. Web. 26 July 2016

[9] Von Bergen, Franz. “Militares controlan más ministerios con Maduro que con Chávez”. El Nacional. N.p., 25 October 2015. Web. 1 August 2016

[10] Kurmanaev, Anatoly. “Army Gets Shiny New Cars as Venezuelans Queue for Food”. Bloomberg News. N.p., 29 September 2014. Web. 1 August 2016

[11] Martín, Sabrina. “Venezuela Buys Weapons As Food Shortages Become the Norm”. PanAm Post. N.p., 28 February 2016. Web. 26 July 2016

[12] “Antonio Rivero: Los militares están muy descontentos por la crisis en el país”. El Nacional. N.p., 31 January 2015. Web 26 July 2016

[13] SIPRI Military Expenditure Database (2015). Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

[14] Martín, Sabrina. Idem.

[15] “Venezuela opposition leader Capriles says army must choose”. BBC News. N.p.,18 May 2016. Web. 1 August 2016

[16] Unchecked Power: Police and Military Raids in Low-Income and Immigrant Communities in Venezuela.” Human Rights Watch.N.p., 4 April 2016. Web. 26 July 2016

[17] Seligson, A. Mitchell. (July 2007). “The Democracy Barometers: The Rise of Populism and The Left in Latin America.” Journal of Democracy (John Hopkins University Press). 18 (3): page 90