Safe Schools Declaration: A Promising Response to Attacks on Education

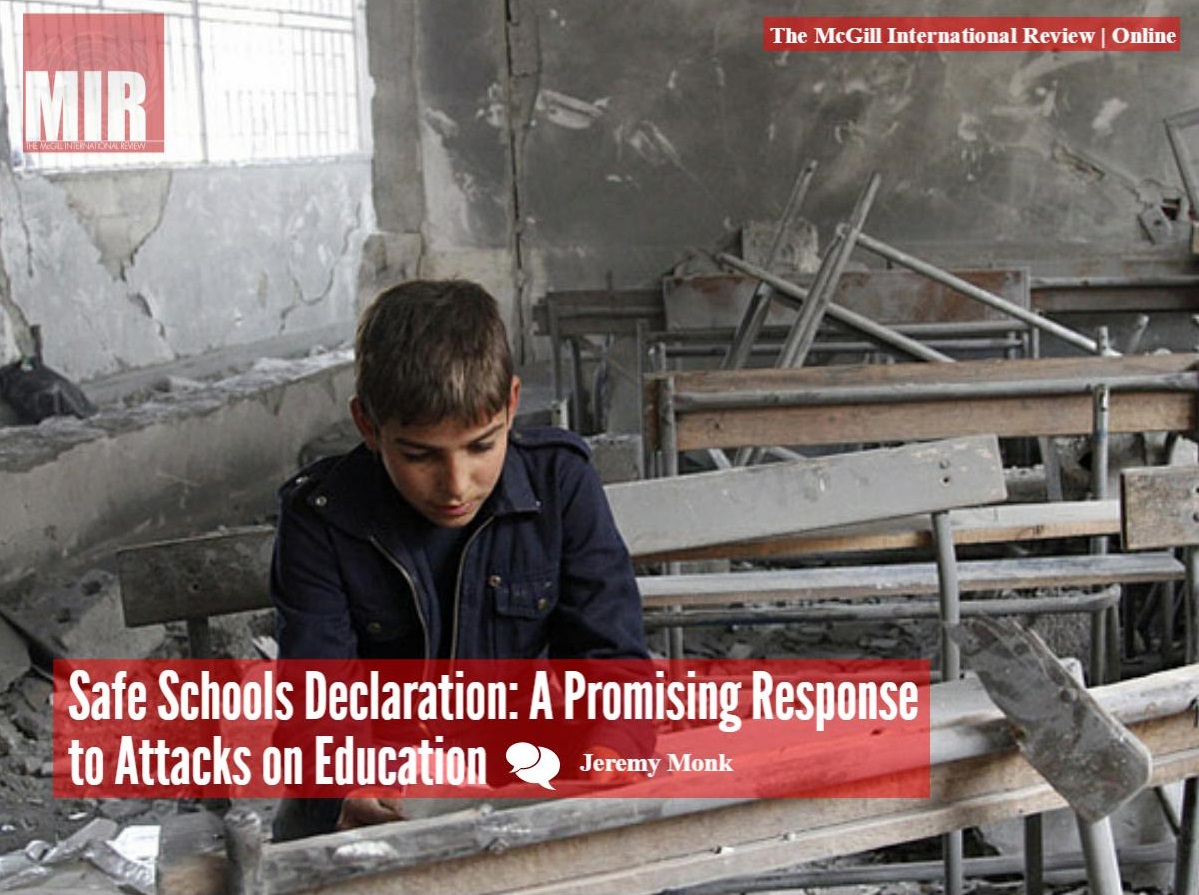

Western news media has adequately reported on important cases of attacks on education in the developing world over the past several years. The 2012 attempted murder of Malala Yousafzai and two other girls on their way to school in Pakistan made international headlines. In 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 girls from a secondary school in Nigeria, and the Taliban attacked an army-run school in Peshawar, Pakistan, both also grabbing worldwide attention. The deliberate targeting of education in wartime and through terror attacks has been steadily on the rise. Researchers at the University of Maryland’s Global Terrorism Database maintain that levels of attacks on education and schools are higher in this decade than at any other point in the last four decades. According to the Global Coalition to Protect Education from Attack (GCPEA), between 2009 and 2014, 70 countries experienced assaults on schools, with many attackers specifically targeting girls’ access to education. In wake of this disturbing trend, the Norwegian government hosted the Oslo Conference on Safe Schools (May 2015), which saw the creation of a Safe Schools Declaration with 37 states and major non-state actors, including UNICEF and Save The Children, as signatories. Despite the surrounding international media outrage, there has been a lack of meaningful action by powerful states to prevent the occurrence of such human rights violations. While the Safe Schools Declaration is a promising set of guidelines addressing attacks on education, the five UN Security Council countries and many other important western states have yet to sign the Declaration, impeding significant political action.

The Safe Schools Declaration has proposed guidelines for protecting schools during conflict and from military use. It has incorporated parts of the GCPEA’s “Guidelines for Protecting Schools and Universities from Military Use during Armed Conflict,” as well as adding in more specific guidelines in order to better prosecute human rights violators. The Declaration states that governments will attempt to restore access to education quickly if schools are targeted by armed conflict or attacks. Countries that have signed the Declaration also agree to make it less likely that schools, students, and teachers are put into dangerous situations in the first place. While this aspect of the Declaration will surely take additional national policy to enforce, countries who have been near the top of GCPEA’s “Map of Affected Countries” have been working closely with the Norwegian government and non-state actors to execute the guidelines of the Declaration at home. These include Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Sudan and Palestine.

In an attempt to avert attacks on schools and education, signatories have committed to better investigate and prosecute war crimes specifically involving schools. Signatories, of which a few are currently involved in civil wars or combating homegrown terrorism, have also agreed to minimize the use of schools for military training, storage, and combat. The ultimate goal of the Safe Schools Declaration is to build an international community which, at a time when attacks on education have increased in frequency and carnage, actively respects the right of children to attend schools. The coalition of countries will develop and share best practices to ensure that schools and students will be protected.

The goals of the Safe Schools Declaration are not ground breaking nor do they pose new commitments, ideological or monetary, for signatories. The initiative is not radical nor should it stir controversy. The Declaration’s proposals are in line with existing laws of war and the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child. The Declaration is attempting to shine light on the growing problem of targeting education as a tool of terror. It is trying to ensure that countries remain committed to keeping civilians safe and to the basic human right of guaranteeing education. However, the Safe Schools Declaration has not been signed by many western countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Canada.

One of the architects behind the Safe Schools Declaration, professor of International Law and former British naval officer Steven Haines, stated that the declaration was not meant to be tough for governments to enforce, and would not embarrass any western governments. However, it seems that a main reason behind the lack of support from western powers is that it could create an avenue in which they could be held more accountable for infractions. According to UNICEF spokeswoman Leah Kreitman, governments and non-state actors have been guilty of breaking international laws in recent conflicts that the Safe Schools Declaration wants reinforced under already existing laws. As many western powers are actively engaging, training or peacekeeping in conflict areas, they may feel that reinforcing human right laws could make them more vulnerable to prosecution. Although the Declaration’s guidelines are not enforceable legally and only attempt to emphasize international law regarding attacks on education, they could be used to embarrass the military and expose other possible breaches of international law.

As is often the case following a tragedy in the developing world, western governments are quick to condemn violent actors and help victims. The west presents a rhetoric that they will be at the forefront of fighting global injustices, especially after they occur. The Safe Schools Declaration is an important step to combat the increase in deliberate targeting of schools during conflict and the use of schools for military operations. In the case of violence against schools and education in wartime, the rhetoric from western states has been strong, but the actions have been weak, visible by the lack of western signatories of the Declaration. While Malala has received numerous honours and prizes from countries and universities in the developed world, including honourary citizenship from Canada last year, there has been a lack of concrete initiatives by governments to aide in Malala’s goal of safe access to education. Without the support of western states, who are reluctant to sign the Declaration in fear of drawing attention to crime they themselves may perpetrate, its impact cannot be realized to the fullest extent, ultimately hurting students worldwide.