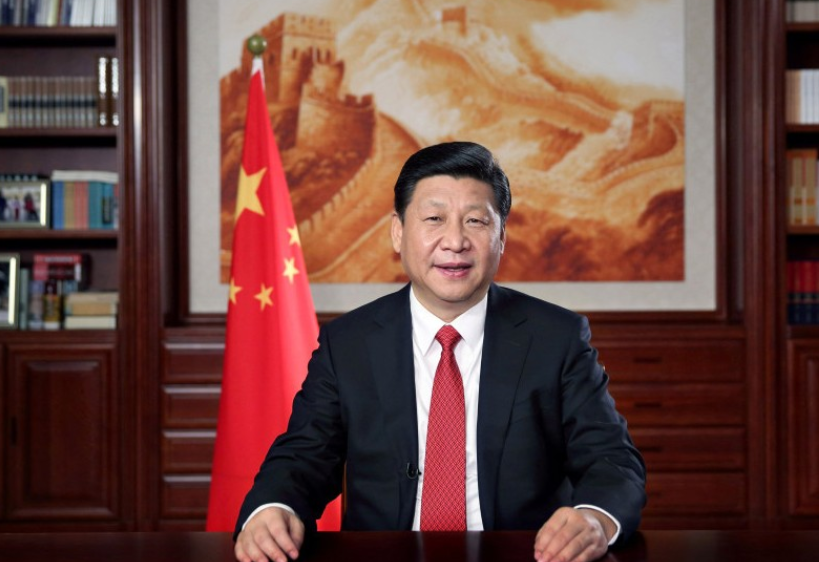

Xi’s Consolidation of Power: Why China May Define our Future World Order

On October 27th 2016, the world watched as China officially named its President Xi Jinping the ‘core leader’ of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at the Sixth Plenum of the 18th CCP Central Committee. In the new directive released through state media, all party members should “closely unite around the party center with Comrade Xi Jinping as the core…and unswervingly safeguard the party leadership’s authority and centralized unity.” It is not simply a trivial label – it is a title that has significant symbolic and historical meaning – one that could potentially signify the rise of a new China in the immediate future, a China that could wield more power on the global stage than ever before anticipated. The world must watch out; this latest power shift in Asia is not an isolated one, it marks the beginning of a crucial and changing dynamic in the world’s balance of power which highly favours Chinese influence. The West has failed to adapt to or contain such a dynamic – and has perhaps even facilitated it, albeit unwittingly.

Perhaps the single most significant implication of this new title ‘bestowed’ upon Xi is a historical one. The term ‘core leader’ has not been in use since the post-Cultural Revolution period in China, when then-leader Deng Xiaoping used it in reference to Mao and his own successor Jiang. What is different in this current context is that unlike the previous three ‘core leaders’, the title is not one borne out of revolutionary struggle and given by another statesman; it is one wholly derived by Xi in reference to himself, which speaks volumes about the magnitude of change he is looking to effect and the type of power he is working to consolidate.

Secondly, the title gives Xi paramount power over the entirety of the CCP, paving way for rapid centralization, effective removal of opposition, and efficient policy-pushing – all of which contribute greatly to Xi’s consolidation of power. In fact, Xi’s newfound power over the party has already manifested itself in an admission of defeat from China’s Premier, Li Keqiang. Li called upon the “leading party group of the State Council, China’s cabinet, and various departments to keep their thoughts, politics and acts in line with the CPC with Comrade Xi at its core.” As second in command of the country, Li has proven to be extremely competent in his role, and was previously known as perhaps the only leader who possessed the capability of challenging Xi, a fact which appears to have been a cause of a growing factional dispute within the country. Nevertheless, it seems now that through his newfound title, Xi has eliminated this remaining threat to his full consolidation of power – further cementing his indomitable position of power, a position that, once again, has not been seen since the post-Cultural Revolution era. Just last week, Xi also removed prominent Finance Minister Lou Jiwei, a CCP veteran who had tried to push for economic reform, replacing him with a little-known tax administrator. Lou’s removal was in fact only part of a large shuffle of positions, announced on November 7th, which brought in new ministers and ousted old ones, including the Minister of State Security Geng Huichang. Predictably, the radical shuffle promoted only Xi loyalists. As Wu Qiang, a Beijing-based researcher and formal lecturer at Tsinghua University, assesses “it’s a clear statement that any dissent or resistance to Xi’s authority, even coming from the highest levels, can and will be punished.”

Furthermore, Xi’s title as ‘core leader’ guarantees a second five-year term extending until 2022, and potentially a third, which is against the current rule of succession in China. However, with this new title, Xi is significantly better positioned to actualize a continual rule – erecting a scheme that is eerily reminiscent of a Putin-esque manoeuvre. What Xi will do with this power is a pressing question at hand, as it will undoubtedly shape Chinese influence in the world for decades to come.

Beijing is already showing signs of more aggressive policy against Hong Kong. Following the recent election of by blocking them from taking office, an action highly unprecedented. On November 12th, Xi Jinping gave a 45 minute speech detailing that “It is our solemn pledge to the people and to history never to let the country be torn apart again. All forms of separatist activities will be resolutely opposed by the entire Chinese people.” By virtue of his actions and subsequent statement, Xi has also established a mechanism by which the authorities can more effectively silence critics of the Communist rule, further contributing to Xi’s preservation of power. China has traditionally kept Hong Kong on a loose leash, allowing annual vigils for those killed in the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre and even huge demonstrations for free elections. Xi’s recent move in regards to Hong Kong reflects a certain testing of the waters – gauging the reactions of the world on the limits China will go push. It appears to have worked. Amidst the separatist struggle, foreign powers that simultaneously and hypocritically refer to themselves as champions of freedom and democracy have failed to issue a real response. And why would they? World hegemons and former great powers are themselves struggling with democracy. Europe is broiled in questionable election prospects and shifts in balances of power that would have been unthinkable a mere year ago. The UK is still grappling with the aftermath of the Brexit decision and its implications, while the US is reeling from the shock of its own election result. Conditions are, in fact, perfect for China to test its global reach, to take advantage of the temporarily crippled Western world.

China’s role as police of the Eastern Hemisphere may also undergo significant changes in the near future, given the coupling of Xi Jinping’s more aggressive policy with President-elect Trump’s foreign policy as laid out for China. Although Trump has accused China of “raping” the United States and promises to bring jobs back home, he seems to have little interest in Asia geopolitically, preferring a purely economic-based foreign policy. His stance, on the whole, will be more favourable to China’s growth in geopolitical influence in coming years, as opposed to a Clinton presidency, by means of giving China ample room to expand its global reach – and thus playing directly into China’s vision. Firstly, if Trump was to follow through on his talk of forcing countries such as Japan and South Korea to pay for their own military defence, which have been traditionally US-funded, China would undeniably be subjected to weaker opponents in the East Asian hemisphere’s struggle for dominance. China would therefore be given the opportunity to expand their own sphere of influence – a position that is surely amenable to their status in the ongoing South China Sea dispute. Secondly, Clinton has shown a certain hawkishness in regards to China’s human rights record and their territorial rights in the South China Sea that President-elect Trump does not seem to share, thereby allowing China further geopolitical leeway to expand.

One very real example of the power shift that is occurring in the Asia Pacific currently is Philippines’ President Rodrigo Duterte’s shift in foreign policy regarding the South China Sea dispute. After announcing a “divorce” from the United States, Duterte announced that the dispute would “take a back seat” in talks with China. His declaration came even after the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague ruled in favour of the Philippines, stating that China had no territorial right to the region. Duterte’s policy is an indicator of how China’s growing power is already being received in Southeast Asia – he is essentially undermining the influence of the United States and the Western world in favour of the power China could potentially provide. Further, the move in itself concretely legitimizes China’s policy regarding the South China Sea. This is not limited to the Philippines, however; it will have regional impact through the potential influence on the foreign policies of neighbouring Southeast countries such as Vietnam or Laos – which would further feed into Xi’s play at gaining larger spheres of influence. As much of the Western world’s attention is focused on issues of refugee intake, Brexit ramifications, and the new U.S. President-elect, it is neglecting the very evident power shifts happening in Asia, thereby potentially allowing a vacuum for China to exploit.

China’s political and economic power is growing at what seems to be an unparalleled rate; a fact which is only amplified by Xi’s newfound status as ‘core leader’ and his continual and rapid centralisation of power. Based on the current global situation in which we find ourselves, it seems that the world can only watch and wait for China’s drive into the future – which is a position of passivity to say the least.