Power Politics and the Environment: Destruction of the South China Sea Reef

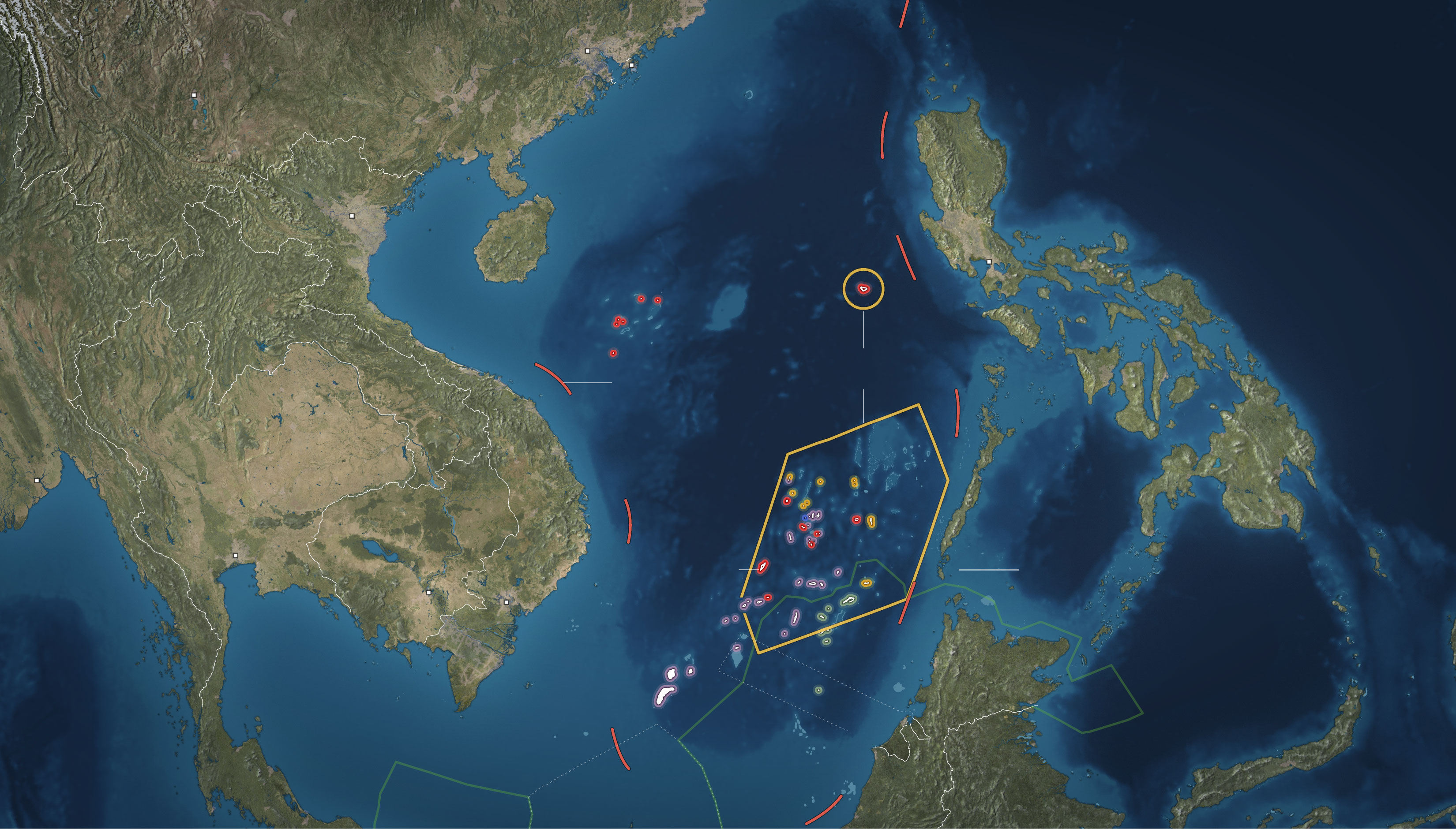

South China Sea Reef disputed claims. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/30/world/asia/what-china-has-been-building-in-the-south-china-sea.html

South China Sea Reef disputed claims. http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/30/world/asia/what-china-has-been-building-in-the-south-china-sea.html

In examining the South China Sea dispute, one ordinarily accords attention to its legal nuance, military development, and saber-rattling. However, one of the greatest victims of the situation is the regional environment. The cost of development in the sea and fishing, which has increased greatly over the past few years, has wreaked environmental havoc upon the region.

China has sought to cement its claim to the distant Spratly Islands by building islands, which their military forces then proceed to occupy. The Spratly Islands is really a misnomer considering that the majority of its features do not qualify as islands, but rather rocks or submerged reefs and shoals. This is an important distinction as an island merits a 200 mile economic zone, whereas reefs and mere rocks do not.

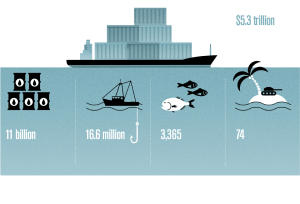

The primary goals for controlling the sea area include access to fisheries, control over the movement of trade and resources that move along the international trade lanes, and rights to the unknown quantities of oil which lie beneath the sea bed. Thus, by building something to be classified as an island, the Chinese military and government aim to have control over the wider neighborhood. The other claimants to the Spratly Islands — Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines — have challenged China’s 9-Dash-Line many times over the years. Whether it be squatters rights or a sense of fait accompli, China has strong motives behind the island-building.

Source: C.I.A., NASA, China Maritime Safety Administration

However, the process of building the islands is disastrous on the local environment. In creating land, where before there was nothing but rock or submerged shoal, these Chinese maritime engineers move mass amounts of sand, thereby suffocating reefs and making the swirling sand prevent light from reaching the plants or fish. The reef ecosystem is very delicate and this abnormal environmental change is causing irreparable damage.

Accusations of environmental irresponsibility have been vociferously denied by the Chinese administration. Chinese diplomat, Hong Lei, has gone so far as to say that the island building project is a green one. He bases this on the idea that the process is a natural simulation of the power of waves in gradually moving sand over years. However, unlike in nature, these changes are not gradual on the timeline of a millennia, but rather over weeks and months. Minister Hong went on to say that once the project is completed, the international community can expect an improvement on the situation, “Once China’s construction activities are completed, ecological environmental protection on relevant islands and reefs will be notably enhanced and such action stands the test of time.”

John McManus, professor of marine biology and fisheries and director of the National Center for Coral Reef Research at the University of Miami, contradicted such a view during a conference on the South China Sea at the Center for Strategic Studies (CSIS). According to McManus, not only does the Chinese reef-building system not in the slightest resemble a natural process, but China’s combination of dredging the sands and then building islands from it “kills basically everything.”

The island building is calamitous for the maritime environment, but it causes a much lower level of destruction on the reef system than giant clam fishing does. While one can blame China’s island building practices for the destruction of 55 square kilometres of reef, giant clam fishing has destroyed over 104 square kilometres of reef. Often China declares that they build on dead reefs, but what diplomats do not mention is the fact that government-approved fishermen are the ones who killed the reefs in the first place.

The giant clams are taken partly for their flesh, but largely for the shell itself. The problem has existed for many years in varying degrees. In the 1980s the colourful species was used for an aquarium fad in China. Now, the fishing of them has gained more momentum, as the shells and carvings made from them have become a new luxury and status good in China, already the final destination for many endangered species. The shells are used as decoration, jewellery and carvings; Tanmen, a harbour town along the Hainan coast, now has streets of stores selling clam products, which can yearly earn 1.5 million (USD).

The fishing of the species is dangerous not only in light of its decimation of the species, which environmental organizations already recognize as vulnerable. The reef is a fragile and vibrant ecosystem and many species depend on the clams. In order to remove the clams, Chinese fishermen use the propellers of their boats to loosen the shell, in the process destroying the surrounding reef. From an economic focus, a coral reef is the most valuable ecosystem per acre in the world. For many years the Chinese government had recognized the status of endangerment on the clams, and forbidden the fishing of them. However, starting in 2013, at the same time as the emergence of Chinese coast guard ships in the Mischief Reef area, and soon before construction began, they completely reversed their policy on this. In light of the easing on the laws and a crackdown on ivory trade, the giant clam trade is now booming.

Many point to China’s very recent policies against clam fishing in their defence, but the 2014 Xi Jinping visit to the fishermen on the Hainan island Tanmen, the epicenter of the trade, belies such change. Xi Jinping is by nature a very political figure and his appearances with Chinese people are infrequent. His day spent in Tanmen, would therefore perhaps point to a more significant, underlying political motive.

For the South China Sea region in general, but especially for China, fishing is not only an important economic asset; it is also an expression and manipulation of politics and a way to change the facts on the ground, or on the waves. China suffers from both legal and legitimacy issues in the South China Sea. In 2012 the Philippines brought a suit against China to the United Nations. The Philippines objected to the Chinese occupation of the Scarborough Shoal, which had been in Philippine territory. They also objected to the forced exclusion of the Philippine fishermen. The Shoal fit neatly into China’s created Nine-Dash-Line, and they of course argued along this principle.

The legal ruling dismissed China’s Nine-Dash-Line claims in much of the South China Sea. China protested the ruling and has not abided by it in the months that have followed. As they did not participate (although the UN invited Chinese legal representatives), they say the court and its ruling are not legitimate. The UN decision wasn’t clear in every section, but on the topic of Chinese fishing practices, it was very clear in its disapprobation. Chinese fishing had been heavily conducted in the areas around the Second Thomas Shoal, and Mischief Reef-the Mischief Reef area is now home to the largest of China’s new islands.

The UN agreed with the Philippines’ protests that the Chinese are fishing in Philippine waters based on the interpretation of Article 121 of the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea, which states that, “Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” Any rocks claimed by China in the area do not merit an economic zone, and thus, the rights to the waters revert to the Philippines whose 200 nautical mile EEZ encompasses the area.

http://bit.ly/2bPaHDc

As part of their case, the Philippines submitted evidence that the Chinese fishermen fished illegally with the approval and support of the government. The UN received reports that Chinese naval ships escort fishermen into these areas. Based on the government’s condoning of illegal practices, the UN ruled that China has breached its obligations under Article 58 (3) of the Convention on the Laws of the Sea. Fishermen receive government protection, and when Xi Jinping made his visit to Hainan he told the fishermen how the Chinese government would do even more to protect them. In 2013, a large Chinese fishing fleet of 30 vessels from the Hainan province conducted a “40-day operation” in the South China Sea. This is the second such operation organized by local fishery associations after China established Sansha City in June 2012. Each vessel in the fleet weighs more than 100 metric tons. Further, a 4,000-ton supply ship and a 1,500-ton transport ship were supplying the fishing vessels with fuel, food, water and other necessities.

All sides seek to gain legitimacy in the dispute, which has negative consequences on the environment. If one side advocates for more environmentally friendly policies, the other disputers feel obliged to do the opposite to show that they do not respect the right of the other country to announce let alone declare such a standard. All this is to the detriment of one of the most biodiverse areas in the world.