A Year After Landing: Syrian Refugees in Canada

https://flic.kr/p/9YJV79

https://flic.kr/p/9YJV79

Last December, Canada welcomed its first batch of Syrian refugees to Toronto. Since then, the Trudeau government has welcomed more than 34,000 Syrian refugees into the country. While they are safe from war in Canada, a significant number of them are struggling to adjust to Canadian society.

Refugees are either privately sponsored or receive aid from the government. Those who were privately sponsored tend to fare better, as on average they tend to have more advantageous family connections or a better education. Government-sponsored refugees are mainly selected based on humanitarian need, so it is not uncommon that they would be more reliant on financial support. The federal government has promised only a year of financial support, and with the year coming to an end, more than 22,000 government-supported refugees will stop receiving federal financial aid. Any aid will then be left up to the provincial governments.

Those who were able to overcome the cultural and language barriers were able to find employment. They find pride in being independent enough to stop receiving financial aid. However, those with jobs that do not provide enough to support a family, the loss of their federal financial aid taken away from them is very scary. Without reassurance from the provincial governments or private sponsorship, going into 2017 can be quite daunting.

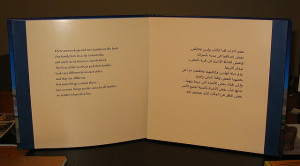

While it would be impractical to indefinitely give refugees financial support, a large population of the refugees need more time to adjust. Some are still in need of a translator to navigate, and the inability to breach the language barrier will make finding a good job difficult. Unlike those who arrived as either primary or secondary school students, learning English or French is an intimidating prospect. Students are constantly surrounded by the language and schools make an effort to integrate refugees into the Canadian culture. For adults, they rely on English as a Secondary Language (ESL) or French as a Second Language (FSL) classes and their community, which is a much looser path to language acquistion. In my opinion, a year is barely enough to learn adequate English or French to enter the workforce. Jobs that deal with customers or require conversations in English or French would be difficult to acquire, if not impossible, with only a year of language experience, which is only further compounded by the fact most of the refugees’ first language is Arabic, so they would need to learn a whole new alphabet to communicate.

Though things may be difficult, Canada offers a safer life than could be hoped for in Syria. Personal accounts of the bombing of their businesses, the dangers associated with their children’s commute to school, and their harrowing journey out of a conflict zone are chilling. While it may be colder and vastly culturally different in Canada, the alternative is incomparable. I hope that the Liberal government will give these refugees more time to adjust to the Canadian way of life, and failing that, that the provincial governments and private sponsors expand their help.