Venezuelan Petrol: Black Gold or the Devil’s Excrement ?

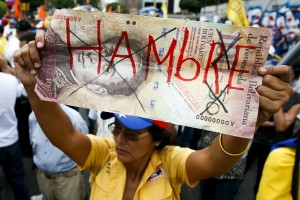

Students march in protest against the government of Nicolás Maduro on November 3rd. Credit: Reuters

Students march in protest against the government of Nicolás Maduro on November 3rd. Credit: Reuters

“Ten years from now, 20 years from now, you will see [that] oil will bring us ruin.” When former Venezuelan diplomat, Juan Pablo Perez Alfonzo, spoke those words in the 1970s, his statement was predictably greeted with puzzlement, at a time when Venezuela was experiencing its first oil boom, which quadrupled government revenues.

Venezuela’s fall from grace would be influenced by two deciding factors: fiscal mismanagement — epitomised by the injection of billions of dollars into unsustainable projects during the administration of Carlos Andrés Pérez (1974-1979)— and increasingly rampant corruption. Despite promises to transform Venezuela into a developed nation, the end result was increased inflation, along with food scarcity, and civil unrest. Sound familiar?

Enter populist and quintessential Latin American caudillo Hugo Chávez—the former coup-plotter was elected president in 1999 by promising poverty mitigation, and elimination of corruption. Generous welfare programs, called misiones, were funded under the auspices of an oil boom, which commenced in 2004 and yielded historically-high levels of revenues. More concretely, between 1999 and 2014, Venezuela received roughly $1 trillion in oil income, and an average of $56 million annually compared to the yearly $15.12 million oil revenues during the administration of Rafael Caldera (1993-1998).

The current picture of Venezuela is bleak at best. Annualised hyper-inflation reached 784.5% in November. Despite four minimum-wage increases instated this year alone by the regime of Nicolás Maduro, the real value of the average Venezuelan salary is expected to fall 373.9% in 2017, compared to the expected 7% average increase across Latin America. Moreover, according to the poll Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida (Encovi), it is estimated that poverty currently affects 73% of Venezuelan households.

To make matters worse, in a country where oil accounts for roughly 96% of exports, Venezuelan crude oil production has shrunk considerably in recent months due to shortages of spare parts, mismanagement, and sporadic power outages. The number of oil rigs in the country has fallen by 25% in the last 12 months up until September, and, for the first time in its history, Venezuela has resorted to importing light crude from the United States to make its own heavy crude suitable for export.

Keystone XL, Iranian Sanctions, and Oil Discovery in Neighbouring Guyana: Trouble in Caracas

When Donald Trump snatched a surprising victory in the November 8 U.S. presidential election, Venezuelans had reason to panic. With the triumph of the demagogic leader came the revival of the Keystone XL Pipeline—an oil duct which would carry crude oil from Alberta to the United States—and with it a project that would wean the American economy off oil from sources outside North America, most notably the Middle East, and Venezuela. Considering that both the incumbent Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau and the American President-Elect Donald Trump have voiced support for the pipeline project, the approval of Keystone XL seems within the realm of possibilities–a threat that could “have a devastating effect” at the “worst moment” for Venezuela according to economist José Toro Hardy.

That Keystone XL could essentially enable Canada—already accounting for 45% of total crude imports in the U.S.— to dethrone Venezuela from the U.S market, is ominous for two reasons. Primarily, Venezuelan oil represents 20% of total American crude imports, and the United States is one of Venezuela’s main markets. Additionally, Venezuela’s oil needs to be refined to be sold, and with Keystone, percolates the possibility of losing access to the U.S. Gulf’s refineries. That would mean investing more money domestically on oil refineries, which, at the present moment, is simply a chimera due to the state-oil company, PDVSA’s possibility of defaulting on its debt obligations, and the myriad of other policy challenges that should take precedence in a state facing chronic food and medicinal shortages, hyper-inflation, and crumbling infrastructure.

Also, due to manifest benefits Venezuela stands to lose with its third-largest oil importer, India, the lifting of economic sanctions against Iran has been particularly consequential. When sanctions took effect in 2012, Venezuela represented merely 4% of Indian imports of crude, compared to 12% currently. Between 2011 and 2014, oil shipments to India from Venezuela skyrocketed 150%, whereas Indian imports of Iranian crude declined from representing 16% to 6%. Since the removal of several sanctions in January, Iranian production of crude has risen by roughly 33%, to pre-sanctions levels, and Iranian officials have recently announced ambitious production targets for 2021. Iran’s resurgence as a global exporter of crude is significant for the Bolivarian republic insofar as China and India collectively receive 54% of Venezuelan crude exports, and the eventual lifting of sanctions could quite simply make trade with Iran more convenient due to its relative proximity.

Additionally, recent discoveries of oil along the coast of neighbouring Guyana by Exxon Mobil Corp last year, could yield more than 1.4 billion barrels of oil with ongoing explorations underway. Although the current estimation of reserves is a far cry from Venezuela’s proven oil reserves of roughly 298 billion barrels, in the medium-term, the U.S. could favour Guyanese over Venezuelan oil as a stick against the increasingly authoritarian Maduro government.

Economic marginalisation is crucial so long as it is accompanied by regional political exclusion. While it has recently been suspended from the regional Southern Common Market (Mercosur) trading bloc, a further measure to accentuate the regime’s status as a pariah would be through the invocation of Article 20 of the Organisation of American States’ (OAS) Democratic Charter to suspend Venezuelan membership. Through such actions, the little democratic legitimacy the government could claim to enjoy externally would be all but null, and could effectively force the regime to grant political concessions—the opening of a channel to humanitarian aid, the reinstatement of the recall referendum to democratically oust the president, the release of political dissidents and reform to the National Electoral Council and the Supreme Tribunal of Justice—to the opposition, or provide the impetus for greater popular mobilizations against the Chavist regime.

Uncle Sam’s Isolationism; Canada’s Power Play

If the U.S opts indeed for isolationism—reneging on trade deals, and removing the promotion of human rights as a cornerstone of American foreign policy— Canada will stand to gain a greater role in Venezuela, as well as Latin America more broadly. In part due to its long-standing unbroken diplomatic relations with Venezuela, and its lesser stain from interventionist operations throughout Latin America in the twentieth century, Canada enjoys greater credibility that would enable it to play a greater role in the short-term and in the long-term once the Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV) is ousted. In the immediate future, Canada would economically directly benefit from the pipeline project, thereby offering the Chavist regime a lesser chance to give the economy a semblance of vigour permitting a triumph in the next municipal and presidential elections.

In addition, Canada can play a direct political role in incentivising members of the OAS to invoke Article 20 of the Democratic Charter and suspend Venezuela from the organisation through its size, its relationship with other Commonwealth countries in the Caribbean, and its democratic credentials. After the post-Maduro era begins, Canada should increase its bilateral relations with Venezuela in several ways: providing direct development assistance–what it does not yet do – aiding the oil rentier state in diversifying its economy using resources with which it can develop a comparative advantage, and further cooperating with civil society organisations promoting democratic governance.

As long as crude represents the only pillar of Venezuela’s economic identity, and sovereignty, any measures taken to safeguard against mismanagement of oil income will merely be band-aid solutions. The spectre of a perfect storm lies ahead, and weaning La Gran Venezuela off oil is the only viable means to re-mediate the adverse effects of Keystone XL, Iranian oil ambitions, and continued oil discoveries off the coast of Guyana. Nicolás Maduro may have a solid grip on power at the present moment, but future developments risk putting his regime on a collision course with aggrieved Venezuelans. Two oil booms and two oil busts later, Venezuela’s black gold, appears to be exactly what Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo thought it would be. Much of the devil’s excrement still lays buried deep under the Orinoco Belt as the crisis worsens.