Queer Ancestors: Bequeathing Stories to Fractured Minorities

A mural by Keith Haring captures queer culture during the AIDs epidemic. https://flic.kr/p/52x4Hs

A mural by Keith Haring captures queer culture during the AIDs epidemic. https://flic.kr/p/52x4Hs

“As gay people, we get to choose our families, and you—you are my family,” the legendary drag performer RuPaul mused at Pride Toronto last summer. This quote, widely cherished in the LGBTQ community, epitomizes both the curses and charms of queer connections. Without biological lineage, the opportunities for intergenerational mentorship are limited. Therefore, a crevasse divides aging generations of queer folks who fought for our rights from queer youth who are coming to terms with their sexual and gender identity. Indeed, the verbal history of older queers vanishes without kin to bequeath their stories. In Canada and the United States, nine out of ten LGBTQ teens have been bullied at school in the past year, and are four times more likely than heterosexual teens to attempt suicide. In addition, an estimated 40 per cent of homeless youth identify as LGBTQ. Consequently, ostracized teens who are banished from their biological clan desperately need supportive networks of older queers for acceptance, advice and loving catharsis.

I spoke with Tyler, an LGBTQ activist and sex worker in Montreal who recalls the inaccessibility of queer mentorship in his youth: “I have suffered a lot, but I feel like (as I’ve grown up) I’m part of something bigger than myself. That’s what connecting to older people, to queer history, has been for me.” Through the emotional labour of sex work, Tyler has listened to the stories of older clients. “I think older people can be really alienated from the gay community too, despite being the people to make it even possible.” Tyler blames the ageist trope of a predatory homosexual, a stereotype that targets senior men in particular, in furthering this generational void.

In the absence of queer mentors, representation in media has become a beacon for LGBTQ youth. YouTube in particular has functioned as a surrogate parent for thousands of queer millennials who have sought advice from social isolation. Through the power of storytelling, vloggers like Troye Sivan, Hannah Hart, and Tyler Oakley have inspired, nurtured, and saved lives. Still, we—and indeed all minorities—need greater intersectional dialogue across the generations of our tribe.

In junior high, when a poisonous cocktail of teen angst, heteronormativity, and sexual confusion unhinged my identity, I remember turning to the tacky musical theatre series Glee for answers. I clung to representation of queer characters like Kurt and Blaine who gave me insight into the culture of my community. For religious congregations there are rituals to pass down customs and values, but for an isolated 13-year-old, Glee was groundbreaking for simply showing that people like me do, in fact, exist. Although representation in series like Glee helped me navigate the waters of homophobia, this journey is more painfully turbulent for many trans kids and queers of colour. Laurie Penny, a feminist author, critiques the 2010 social media campaign It Gets Better, which was intended to give solace to queer children with suicidal thoughts. Penny writes “for LGBT youth it gets a whole lot better a whole lot faster if you’re white middle class and moneyed, like every other empty neoliberal promise tossed at millions of hurting, lonely kids.” While the premise of saving queer kids is admirable, the movement illuminates how white experiences guide gay liberation movements. As wealthy white homosexuals pen the “gay agenda,” the contributions of marginalized members are often erased. Tyler believes that “the sort of corporatized Disney gayness only works for certain privileged gays, and ultimately masks so much violence.” At the forefront of the Stonewall Riots were trans women of colour, and yet more heterosexual men are featured on the cover of mainstream LGBTQ magazines than people of colour. While banners glorify queer inclusivity and unity, the colours of the rainbow family remain hierarchically segregated.

This fragmentation of queer realities was made visible in 2016 by the backlash that Black Lives Matter received after staging a protest at Toronto Pride. Many attendees were unable to acknowledge how their white privilege filters their experiences with law enforcement, and consequently scorned the perspectives of those protesting. Andrea Houston argues that “police harassment of queer and trans people is not even historical. Sex workers frequently say that they march next to the same smiling, bead-covered cops at Pride who will turn around and arrest them and their clients in the Village the very next day.” These experiences remain invisible for privileged queers who shimmy with brigades of police officers during Pride and remain unaware of the systemic police brutality that assaults queers of colour. As a result, the burden of representation falls on subjugated populations to prove their oppression to privileged queers who think racism has been largely solved.

Queers must query: what kind of family is this? How can we have solidarity across racial and class lines while members of our community dominate oppressed populations?

To even begin reconciling these issues, we need to acknowledge these power dynamics and centralize the stories of those who have been erased. For all the strenuous hours I spent studying history from grades one to twelve, I can only recall a miniscule blurb that credited the contributions of LGBTQ people to Canada’s history, never mind queer people of colour. These stories deserve to be told. The platforms of social media, theatre, and television are essential in humanizing vilified populations. Through the Internet and the performing arts we can reach the hearts of those beyond our like-minded silos, to amplify the wisdom of those on the margins.

Representation in the media has been an important touchstone for other communities as well. Growing up as a biracial musical theatre performer, Morgan Wood was inspired by trailblazing artists like Audra McDonald, Jennifer Hudson and Patina Miller. Morgan believes that “theatre is moving towards a more diverse, multiracial structure. Shows like Hamilton and The Color Purple provide a voice to minorities unlike any before.” Nevertheless, the prevailing norms of white supremacy ensure that not all representation is productive. Morgan notes, “for so long minorities have played stock characters that either mock the fact that they are a minority or exploit that in a destructive way, such as black women who only ever play lower class roles, or Spanish women being cast as the seductress.” Even as roles are created for ethnic and sexual minorities, production and writing teams remain oversaturated with straight white males. Of the top 250 films produced in 2015, only seven per cent featured female directors cent. Even feminist series like Orange is the New Black, which has been lauded for its diversity on screen, holds no African American women on its writing team.

Without placing queer folks and people of colour behind the scenes, characters are constructed based on stereotypical assumptions rather than the complex lived experiences of minorities. In addition, predominately white audiences often fill the seats of productions like Hamilton—which celebrates racial diversity both on and off stage—as they remain financially inaccessible to lower income communities whose culture it celebrates.

Even YouTube, which is structured to be accessible, has recently created content restrictions that discriminately censor LGBTQ videos. The music video for Tegan and Sara’s “Alligator Tears,” (which features innocent dancing) for example, was labelled “sensitive material” and blocked from being viewed by young queers. The myriad of institutional forces that seek to whitewash ethnic minorities and erase queer stories must be dismantled, especially considering the fundamental necessity of LGBTQ storytelling specifically.

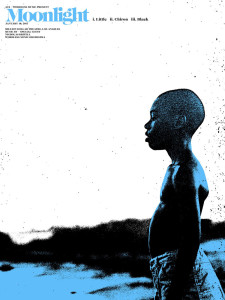

It is devastating to fathom the generations of queer wisdom and art that have perished from centuries of closeted existence and violent censorship, as well as from the AIDS epidemic. Nevertheless, despite relentless opposition the bonds that link racial and sexual minorities have persevered. On a personal note, the simple freedom to write this article without fear of being evicted from my home, shunned by my family, or fired from my job speaks to the legacies of brave LGBTQ ancestors whose achievements I have inherited. There is immense hope in knowing that the stories of contemporary films like The Imitation Game and Moonlight will help mentor the queers of tomorrow. Ultimately it is the stories we tell ourselves in marches and art that bind our family together.