Yin and Yang: China’s Rise and the Future of the Pacific

China is a rising revisionist power, seeking to realign the status quo in the Pacific and assure its security via domination of its periphery regions, after a “century of humiliation.” In 1978, its GDP was a mere US$150 billion, while 39 years later, its economy stands at $11.2 trillion, with the country now standing as the world’s second largest economy and the world’s largest active military force. Its burgeoning strength is demonstrated by its provocative and aggressive expansion into the South China Sea and the creation of its first overseas base in Djibouti. How will the Pacific be affected by a resurgent and aggressive China, what is the source of Beijing’s aggression, and does Beijing pose a threat to the global order?

China’s burgeoning strength in the Pacific is best evidenced by its recently-launched domestic aircraft carrier, the first of its kind. Beijing allocated over $215 billon to its armed forces in 2016. While this pales in comparison to Washington’s $611 billion commitment, the majority of Beijing’s military budget goes into the Pacific, whereas Washington has military obligations across the globe due to its position as the world’s sole hegemonic power. Washington also suffers from the tyranny of distance, whereby to reach Asia, Washington must cross the vast Pacific Ocean. Meanwhile, Beijing lies on its doorstep, allowing Beijing to exert greater influence over the region at less cost.

To China, this is merely a return to form after surviving what it terms “A Century of Humiliation” at the hands of the Western powers between 1839 and 1949, when China was forced to make humiliating concessions following a series of disastrous defeats. Beijing was sacked, China’s prestige was destroyed in the Opium Wars, and the country lost of over a third of its territory. This has had a profound impact on the founding of modern China, as it harbours great distrust towards Western encroachment in the Pacific. In 2004, Chinese president Hu Jintao told the People’s Liberation army, “Western hostile forces have not yet given up the wild ambition of trying to subjugate us.” This sentiment is not unique, as PLA publications in 2005 assert that Western nations are aggressive and greedy, owing to their historical roots as “slave states that frequently launched wars of conquest and pillage to expand their territories, plunder wealth, and extend their sphere of influence.” In contrast, China is portrayed as a “peace-craving and peace-loving” state.

Beijing is further emboldened by Washington’s Island Chain strategy envisioned during the Cold War, where it sought to contain communism via 2 island chains. The first envisaged a line stretching from Okinawa all the way across the South China Sea, where Taiwan acted as its central bedrock with an unsinkable aircraft carrier. The second chain was centred around Japan and Papua New Guinea in the Mid-Pacific. While this policy was never officially adopted by the United States, its mere existence has emboldened Beijing to prevent its containment, as history has shown China the dangers of losing control of its periphery regions.

To this end, Beijing has reclaimed what it considers to be strategically vital regions in its periphery, with Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Tibet being retaken in past decades. These regions surround and protect the Han Core, a region home to over a billion people. With these buffer regions secured, China is protected by the imposing Himalayas located in the Tibetan plateau, the arid and mountainous landscape of Xinjiang, and the mountains of northern Manchuria. Finally, the last vestige of Western presence was exiled following the British handover of Hong Kong.

Yet, as demonstrated by the Opium Wars and the Sino-Japanese war, China is vulnerable to its vast coastline that stretches over 14,500 km. PLA publications in 2015 stress a shift into the Maritime regions, due in part to increasing disputes in the South China Sea and the region’s growing importance as protection for China’s trade routes. In addition, Beijing believes the South China Sea is home to over 130 billion barrels of oil; by acquiring such deposits, China would become the world’s second biggest producer of oil. China currently has around 1% of the world’s oil reserves yet 20% of its use. Beijing is looking to nearby deposits to address its energy needs, especially when it’s predicted that China’s energy consumption, as well as the rest of Asia’s, will double by the end of 2020.

Therefore, Beijing aggressively pushes its claims in the South China Sea, building artificial islands and increasing their military capability in the region in the form of asynchronous capabilities. It recognizes its technological inferiority, thus greatly investing in its submarine arm, outproducing the United States Navy by four to one in 2000 and eight to one in 2005. Moreover, in 2017, China commissioned its first nuclear submarines. This in an era where Washington’s anti-submarine capabilities are diminished after a decade of counterinsurgency activities. Washington’s vulnerabilities were demonstrated in 2007, when US Admirals were left dumbstruck as a Chinese submarine surfaced within torpedo range of the now-decommissioned carrier, the USS Kitty Hawk. China’s capabilities are enhanced by the creation of airfields and missile batteries throughout the South China Sea to deter Washington’s activities close to China’s claimed waters and decrease Washington’s credibility in the eyes of its Pacific allies.

Due to a gradual build up of naval ships, Beijing will outnumber the United States in the Pacific by late 2020. With the commissioning of the former Soviet aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, in 2012 and the launching of its first domestic carrier in 2017, Beijing is signalling its intent to match Washington’s capabilities. Until 2016, Beijing’s policy was one of “Taoguang Yonghui,” meaning “hiding one’s brilliance and biding one’s time.” However, in 2016, state-owned Global Times announced Beijing’s intent to demonstrate its military power to the world. Beijing’s growing strength will fundamentally alter the Pacific balance of power that has favoured the United States since the end of the Cold War.

Finlandization: Impact on the Pacific

China’s growth is leading to an arms race as neighbouring states, especially those with disputing claims, grow wary of China’s growing strength. The Pacific region spent over $450 billion on defence spending in 2016, $215 billion of which stemmed from China, and the region does not seem to be slowing down anytime soon. China as a growing power may seek to acquire what the University of Chicago professor John Mearsheimer terms regional hegemony. After all, “The best situation for survival in the international system is to be a regional hegemon — to be by far the most powerful state in your area of the world and make sure no distant great power has come into your region.” Beijing’s willingness to acquire regional hegemony is evidenced by President Xi Jinping’s declaration in 2014 regarding China’s new Asian Security Concept: “It is for the people of Asia to run the affairs of Asia, solve the problems of Asia and uphold the security of Asia. The people of Asia have the capability and wisdom to achieve peace and stability in the region through enhanced cooperation.”

The South China Sea is a region of significant geostrategic importance; more than half of global merchant tonnage and a third of global maritime traffic passes through the region. Therefore, whoever controls the region will gain undue influence over nations that depend upon maritime trade. A case in point is Japan, a nation that is not agriculturally self-sufficient, as data from Japan’s ministry of agriculture stated that Japanese agriculture could only meet 39% of its domestic calorie requirements. Japan’s energy security is more dire, as it imports 94% of its primary energy supplies. For Tokyo, the security of its trade routes are a matter of life and death. Should Beijing dominate the South China Sea, Tokyo would be under significant Chinese influence.

However, Washington currently possesses unipolar hegemony over the Pacific, as the United States Pacific fleet is the largest in the region. Yet, enlarging Asian militaries will lead to military multipolarity in the region. Washington must not falter in its Pacific commitments, as this will lead to a process of Finlandization of states throughout the Pacific. Finlandization refers to a Cold War process whereby NATO and the USSR agreed not to change the status quo in Finland, so long as neutral Finland accepted significant Soviet influence regarding domestic and foreign policy. This strategy is the most likely way in which Beijing will seek to attain regional hegemony. As political analyst Robert D. Kaplan stated, “Finlandization in the case of Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia would mean that these countries would remain nominally independent, but the parameters of their foreign policies would essentially be written in Beijing.” Sovereign countries would lose their autonomy and, to a degree, their very sovereignty, to Beijing. This may be the fate of Asian states such as Taiwan, Vietnam, and Korea should China dominate the Western Pacific. Consider Taiwan, a nation that many Chinese consider sovereign Chinese territory and which Beijing believes to be the final humiliation left to address.

Taiwan is a democratic nation, beset by a hostile Chinese military that currently has over 1500 missiles aimed towards it, kept at bay by the strait of Taiwan and the United States commitment. Yet, 40% of Taiwan’s exports go to China, and the country is already subject to China’s One China policy, barred from claiming sovereignty and stigmatized by most nations who refuse to acknowledge the nation out of fear of raising China’s ire. A statement given by an official in an undisclosed Pacific nation stated, “American military presence is needed to countervail China; the withdrawal of even one US aircraft carrier strike group from the Western Pacific is a game changer.” Should the US falter in its commitment, China may be emboldened to finally correct what they perceive as the final vestige of the Century of Humiliation. In the face of waning US commitments, Asian states throughout the Pacific may seek to guarantee their safety by aligning with China. After all, Beijing’s views on its Century of Humiliation may lead to it becoming overtly aggressive in the western Pacific, seeking to dominate the region through economic and military might just as it has done to the state of Taiwan.

Dominance of the South China Sea would permit Beijing to fundamentally alter the global balance of power, as it would be in a position to revise the current status quo. Beijing claims it will uphold the global rules-based order; however, its actions speak otherwise. Beijing consistently demonstrates its disregard for the current status quo, flaunting the freedom of navigation principle enshrined in the UN convention on the Laws of the Sea. Meanwhile, Beijing declared an Air defence identification zone (ADIZ) over the South China sea, in effect declaring sovereignty over the region and restricting the freedom of navigation in the region.

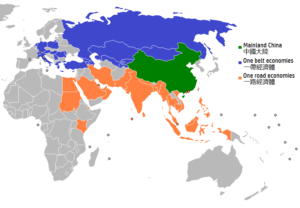

Beijing’s Asian security concept gives it self-contrived legitimacy in claiming that non-regional powers are meddling in Asia’s internal affairs, giving Beijing self-legitimacy in tough counteraction and allowing Beijing to restrict involvement of foreign powers in the region so as to enhance Beijing’s own clout. When the Hague declared China’s declaration of sovereignty over the South China Sea illegal, Beijing called the results a farce, with President Xi claiming China’s “Territorial sovereignty and marine rights” will not be affected by the ruling. Furthermore, Beijing has created its own regional variations of the World Bank, creating the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2016. The bank has an initial capital of $100 billion, roughly half that of the World Bank, and the bank’s creation coincides with China’s sponsoring of the One Belt, One Road project. A global infrastructure project spanning across Eurasia, One Belt, One Road is spurring development across central Asia and undoubtedly increasing Beijing’s influence and prestige, not to mention Beijing’s economic benefits from easing the export of its domestic products.

Yin and Yang: Balance and the Future of GeoPolitics

The future is never set in stone, but certain realities do exist. The first is that the era of American hegemony in the Western Pacific that has existed since the end of WWII is coming to an end. Instead, the coming decades will see the Western Pacific transform into a bipolar struggle between China and the United States. Regional powers such as South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam will be caught in the struggle, and should the US falter in its commitments, these states will most likely suffer from Finlandization against Beijing.

Yet, consider the Yin and Yang, an Asian philosophy centred around the balancing of two opposite forces to create harmony. Half of Asia’s military spending is accounted for by states neighbouring China. Thus, to stymie growing Chinese influence in the Pacific and preserve the independence of Asian states, Washington must in the short term increase its strength in the Pacific, as to form a bulwark which allied nations can gather around. This will assure Pacific nations such as Vietnam, Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan that the US will continue to act as a mediating power against China in the region. If not, then many of these nations may suffer from Finlandization, losing their independence in all but name in order to assuage Beijing.

At the same time, Washington must signal to Beijing that it does not harbour hostile intentions towards China. It should strive to work alongside Beijing in patrolling the high seas, building up bilateral relations between the two as to prevent any future misunderstanding in the region. Washington should continue to invite Beijing to RIMPAC, an annual naval exercise in the Pacific, to build trust between the two navies. It should promote the growth of ASEAN, an organization of Southeast Asian states, in order to foster cooperation and friendly relations in Asia. Washington should acknowledge Beijing’s new institutions that challenge the primacy of western institutions such as the World Bank. Rather than challenge these new institutions, Washington should work alongside them to foster the growth of developing regions.

The rise of the Chinese dragon will undoubtedly be a game-changer in regard to the current balance of power in the Pacific. In the coming decades, Washington must commit to its Asian pivot in order to prevent Finlandization and secure the continued independence of states on Beijing’s periphery. Failure to do this will result in eventual Chinese domination of the Western Pacific, and billions of people in the Pacific will lose their sovereign right to decide their own destiny. As Thucydides claimed, “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.” Yet, a powerful US presence in the Pacific will be required to ensure that even the weak are able to do what they can against a rising dragon in the East.