The Nuclear Kingdom

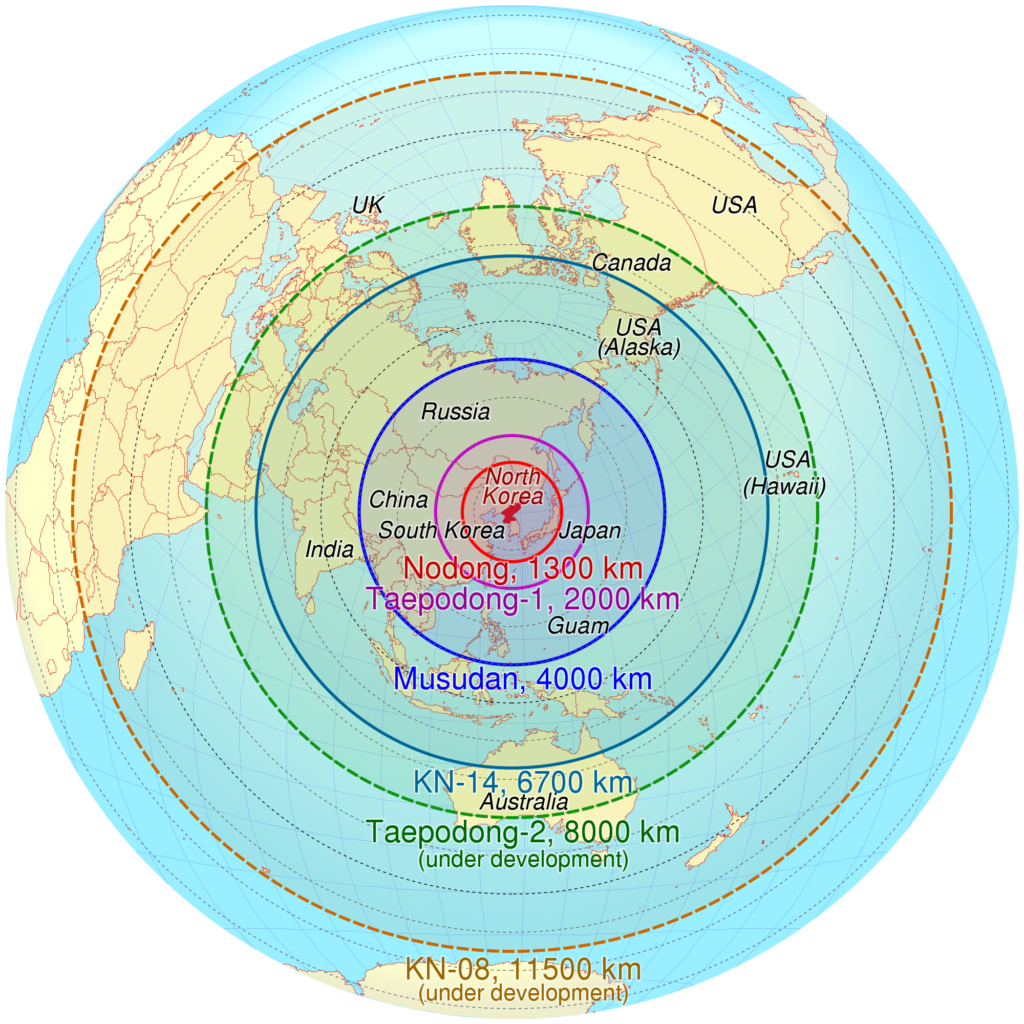

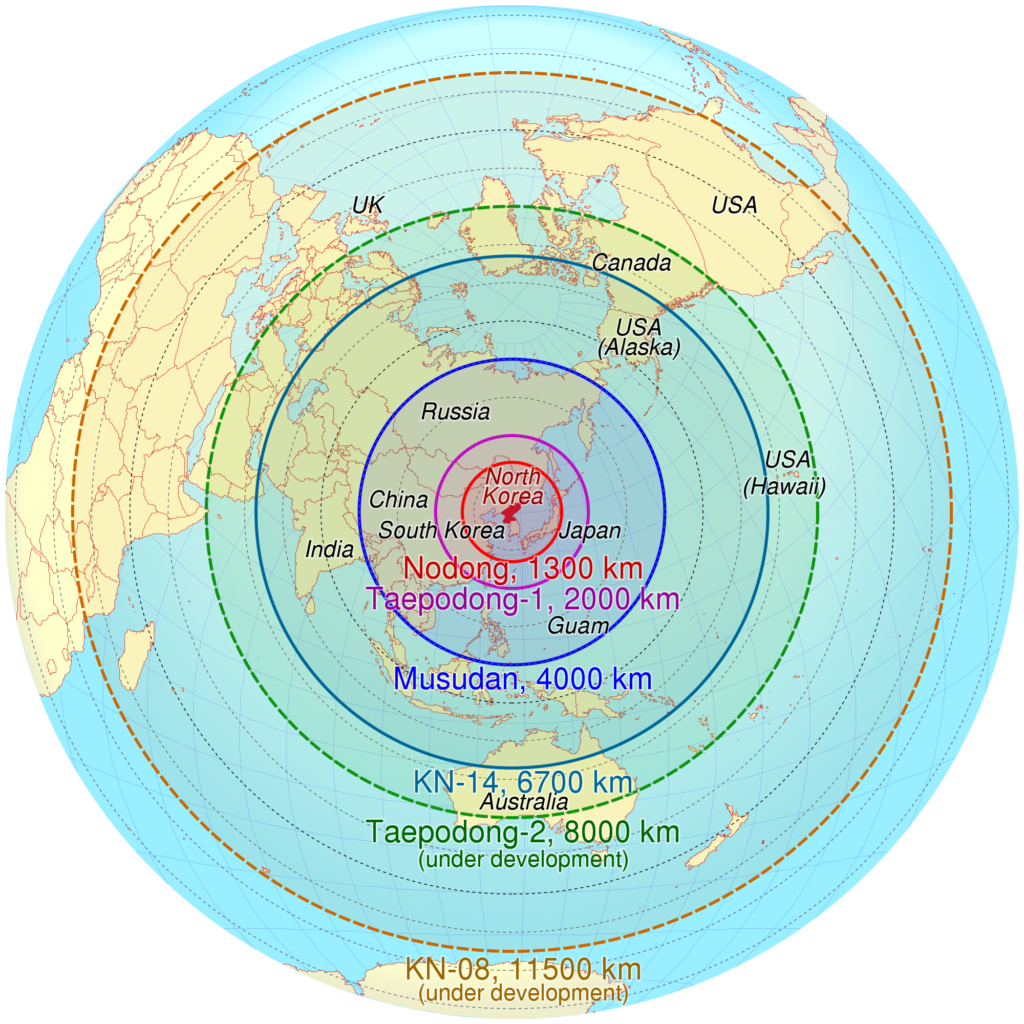

On September 14th, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, colloquially termed North Korea, threatened to sink Japan and turn the United States of America into ashes and darkness. These aggressive statements came in response to fresh rounds of UN sanctions, which prohibited Pyongyang’s textile exports and capped its oil imports as tensions mount over its provocative nuclear and missile tests. Pyongyang’s recent nuclear test was eight times more powerful than the bomb dropped on Nagasaki, and a North Korean missile over Japan exposed Tokyo’s vulnerabilities to a possible nuclear strike. The international community remains on edge as concerns are raised over Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions, whose reckless behaviour and single-minded pursuit of a nuclear deterrence aggravate regional tensions. Pyongyang, despite facing international condemnation, refuses to back down as it pursues the survival of the government through the possession of nuclear weapons.

North Korea is an outlaw state. It is a dictatorial regime that refuses to comply with reasonable international laws and acts aggressively towards foreign states. The source of this aggression lies in both its acute military vulnerabilities against South Korea and internal domestic instability stemming from years of economic mismanagement by Pyongyang.

Militarily, Pyongyang recognizes its vulnerabilities against Seoul. While Pyongyang professes to have a million active soldiers, with an additional 5 million in reserve against Seoul’s 650 000 active and 3 million in reserve, Seoul enjoys a GDP 50 times greater than that of Pyongyang and accordingly spends 5 times as much on its military than its Northern counterpart; Seoul’s armed forces are comprised of modern equipment while Pyongyang’s is comprised of Cold War era weaponry. Thus, Pyongyang has sought to rebalance the scales in its favour by pursuing nuclear weapons. Proliferation is meant to build up nuclear deterrence, and regular demonstrations are meant to warn North Korea’s neighbours of the consequences of conflict with Pyongyang.

Domestically, Pyongyang suffers from a chronic shortage of food and medical supplies, all the while suffering from low rates of productivity due to technological inferiority compared to its more modern neighbours. The source of the issue lies in Pyongyang’s centrally planned economy. For the past two decades, Pyongyang has engaged in “Planning without facts, and planning without plans”.

In light of growing domestic instability during the 90s, Kim Jong Il espoused the mantra of “Perpetual War” against the West, requiring a policy of military first or “Songun” to protect the Korean people. This ideology blamed all the ills of the Korean people on the US as an imperialist power, who North Korea claims has never given up on conquering the North Korean state. This requires tremendous sacrifice by the citizens to protect their way of life, so according to the regime, nuclear deterrence will act as the ultimate safeguard, provided by the great Kim dynasty.

This belief is abetted by the reality that over 20% of the North Korean population was killed during the Korean War, and that the 1968 Pueblo Incident saw the capture of the USS Pueblo while it was on an espionage mission against Pyongyang. Pyongyang points to US sanctions as evidence of continued American aggression towards Pyongyang, ultimately embodied in the continuing armistice that has existed between Pyongyang and its allies since 1953. This armistice stands as an agreement to stop the fighting, but not necessarily the war, which technically continues today.

The policy of Songun permits Pyongyang to single-mindedly pursue nuclear arms despite the suffering of its civilian populace, and Pyongyang sees nuclear weapons as the solution to both its external and domestic issues.

Limiting Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal.

It’s only a matter of time until Pyongyang is able to acquire the means and capabilities of being able to carry out a nuclear strike on the United States of America. Previous international sanctions failed to deter Pyongyang, and fresh sanctions are unlikely to succeed where previous ones have failed. Indubitably, Beijing will continue to economically prop up Pyongyang out of fear that a unified Korea, aligned with America will act as a front yard into China.

Washington should negotiate with Beijing over the Korean peninsula and address Beijing’s fears that a democratic, pro-Western unified Korea would be more threatening to its national interests than anything the North Korean state has done or will do. This will require the cessation of US military presence on the Korean peninsula. From Beijing’s perspective, following potential Korean unification, what purpose will American forces serve if not to contain Beijing? It will additionally require the new Korean state to forgo the nuclear capabilities developed by Pyongyang. If neighbouring nations are wary of impoverished Pyongyang’s limited nuclear capabilities, it’s difficult to fathom the nuclear arms race that will arise following the emergence of a unified nuclear Korea backed by Seoul’s modern economy.

However, even Beijing’s significant clout over Pyongyang will be unable to significantly alter the political situation present in North Korea. While both states profess to have an alliance “Forged in blood” during the Korean War, Pyongyang has consistently sought to guarantee its autonomy in the face of increasing Chinese influence. During the 1950’s, Pyongyang banned the pro-Chinese party “Yan’an Group” and in 2013 Kim Jong Un’s uncle Jang Song Thaek, the senior pro-Chinese politician, was executed. Furthermore, Pyongyang has steadfastly rejected Beijing’s proposals for economic development out of fear it would increase Beijing’s already considerable clout over Pyongyang. It would appear that the Kim dynasty, which has ruled over North Korea for 69 years, prefers to be first a hermit kingdom, then second in allegiance to Beijing.

Nor is Beijing willing to risk a breakdown of relations with Pyongyang. Beijing has consistently advocated negotiations with Pyongyang in lieu of the direct confrontation proposed by Washington. This reflects Beijing’s fear that over-pressuring Pyongyang may turn it hostile towards Beijing, a significant political blow to the Chinese Communist Party, which holds that it won the Korean war despite significant casualties. This victory is a source of national pride, espoused by the party as proof of its political legitimacy against US imperialism, thus the only party able to return China to its pre-eminent status. Furthermore, if China breaks off ties with Pyongyang would it mean that the tremendous cost of Chinese lives during the Korean War was in vain?

China’s unwillingness to abandon Pyongyang is demonstrated by its role in sanctions against it. While Beijing banned coal imports from Pyongyang in 2017, it increased imports of additional North Korean goods to make up for the shortfall, imports which actually increased Beijing’s economic support by 10%. Thus, while Beijing claims to have taken a tougher stance on Pyongyang, its actions demonstrate it is unwilling to risk a breakdown of relations. A breakdown which may lead to western-oriented unified Korea on its doorstep. After all, why would Beijing fulfill America’s greatest desire while ushering in China’s worst nightmare?

That said, only with Beijing’s support can Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions be curtailed. Washington must negotiate with Beijing over the future of the Korean peninsula; Beijing previously called for “suspension for suspension.” This calls for the cessation of annual American-Korean military exercises in exchange for the suspension of Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions. However, the issue lies in that Washington views denuclearization as the first step, while Beijing views it as the ultimate, eventual goal. Washington must work alongside Beijing on this situation; annual war games on Pyongyang’s doorstep do nothing to alleviate its fears of external invasion, and instead legitimatize Pyongyang’s militaristic ideology. Washington’s hard-line approach to Pyongyang has failed, and it’s increasingly unlikely to work as Pyongyang continually develops its nuclear capabilities. By working alongside Beijing, Washington can limit Pyongyang’s capabilities if it does not prevent Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions.

Preventing Pyongyang’s nuclear ambitions will require tough multilateral negotiations between Washington, Seoul, Beijing, and Pyongyang. The parties involved must sign a long overdue peace treaty, as doing so would extend an olive branch to all parties involved and act as an important first step towards peace on the Korean peninsula. All parties involved must gradually lower tensions via the cessation of annual war games, accompanied by the gradual disarmament of both factions. Washington and Seoul should address Beijing’s fear by agreeing to the withdrawal of US military troops on the peninsula following successful unification. Pyongyang’s fears of regime survival must be addressed via a peace treaty which recognizes the current North Korean government, along with mutual disarmament. Only then can the two Koreas work alongside one another with the eventual goal of reunification.

Tacitus once wrote “They make a desert and call it peace”, and this grim reality awaits any future conflict on the Korean peninsula. Pyongyang should not be provoked, as they will certainly strike first if they sense imminent regime collapse at the hands of enemies. President Trump recently addressed the United Nations, stating “Rocket Man (Kim Jong Un) is on a suicide mission for himself and for his regime” and threatening to “totally destroy North Korea” if the US was forced to defend itself and its allies. Such statements do nothing to alleviate the tensions shrouding the Korean peninsula; they only bolster Pyongyang’s grim determination to avoid such destruction through the acquisition of nuclear arms. President Trump once stated he would be willing to meet and eat a burger with Kim Jong Un at the White House. With tensions at an all-time high, maybe it’s time to have this burger.

It is not certain that negotiations will bring peace to the peninsula, yet it’s clear that the sanctions and hardline rhetoric used for the past several decades have not prevented Pyongyang from attaining nuclear arms. Diplomatic negotiations are an avenue that offers peace and possible future unification, and shouldn’t that chance, no matter how slim, be pursued?

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo