Land of the Twilight Sun

Abe Reviewing Members of the Japanese Self Defence Force. https://www.apnews.com/2fd3e138823841d7b8ccfc001ce10caa

Abe Reviewing Members of the Japanese Self Defence Force. https://www.apnews.com/2fd3e138823841d7b8ccfc001ce10caa

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe won a resounding electoral victory on October 22nd, with his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) retaining its 2/3rd supermajority. Buoyed by this development, Prime Minister Abe is likely to continue the highly proactive Abe Doctrine regarding Japanese foreign policy, but what are this doctrine’s implications on Japan and its relations with Asia?

Abe seeks to reclaim Japan’s Great Power status through engaging in a highly proactive “Value Oriented Diplomacy”. This doctrine calls for Japan to increase its contributions to global values of democracy, human rights, and the rule of law through the enlargement of a Japanese Self Defence Forces (JSDF), who are also meant to engage more often in global affairs. It must be noted that Japan does not technically possess a “military”, but instead a self-defence force that just so happens to possess the world’s 8th largest national security budget. Utilizing modern military assets ranging from the innovative F-35 to helicopter destroyers, a class of ships eerily reminiscent of an aircraft carrier and often termed an aircraft carrier in disguise, Japan’s force is formidable. After all, Vegetius wrote “Si vis Pacem, para bellum,” meaning if you want peace, prepare for war.

http://bit.ly/2gT19Mz

The notion of “defence” is increasingly being shifted further and further from Japanese territory, itself an expansion of the already liberal adaptation of Article 9 of Japan’s constitution. Article 9 stipulates that “The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes”. To this end, Japan is constitutionally barred from the formation of armed forces and the right to declare war. Thus, when faced with external threats during the formation of the Cold War, Tokyo established the JSDF, whose capabilities have steadily increased over the past decades as Tokyo was unable to free-ride off an over-extended Unites States during the height of the Cold War in the 1970s.

This shift denotes a more general trend towards normalization of Japanese foreign policy in the modern era, with a shift from the mercantilist Yoshida doctrine into the proactive, and overtly assertive Abe Doctrine, which utilizes Japan’s de-facto armed forces unhampered by constraints. The Yoshida Doctrine was a foreign policy doctrine formulated by Japan’s post-war Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, which stressed the economic development of Japan’s ruined infrastructure and economy by pursuing economic objectives while hedging security interests by free-riding with the United States. The Yoshida Doctrine called for Japan to maintain a low-profile in international politics, quietly biding its time to develop its ruined economy. Seventy years later, Japan is an economic powerhouse, and Abe seeks to reclaim Japan’s place in the sun as a great power. Abe believes this can only occur once Japan overcomes its constitutional constraints and its burden of history. Abe served as the Deputy Chief Security of the Japanese Diet’s (Parliament) Advisory group, the most conservative group Diet’s most conservative faction which advocates for amendment of Article 9, and co-founded the Japan Rebirth group, which calls for Japan to be under conservatives values of service for the greater good, and of traditional Japanese culture.

If handled properly, Japan’s normalization will not be a source of tension. If anything, normalization is inevitable and Abe simply represents the helmsman as Chinese external pressure paired with Japan’s dependency on resource imports mean that its national interests can only be attained through increased JSDF activity. The issue, however, lies in Prime Minister Abe’s controversial views regarding the role of Japan during the Second World War, and the use of Comfort Women. First, conflict in Asia did not commence in 1939 like it did in Europe; the Second Sino-Japanese war began in 1931 with the Japanese invasion of Chinese Manchuria, and a shaky truce established in 1932 broke with the Japanese invasion of mainland China in 1937. This brutal conflict cost the lives of around 30 million Chinese. Japan’s aggression in the region worsened during its conquest of European colonies in order to attain resources and sustain its war machine in 1941 following the imposition of Economic sanctions on Japan as a response to the Japanese occupation of French Indochina. These were preceded by the First Sino-Japanese war, during which Japan annexed Korea, and subjecting Koreans to cultural genocide, a lingering source of tension between the states. Even today, North Korea periodically uses Japanese occupation as a justification for its militaristic policy, which deprives the country’s citizens of state resources while shielding them from powers such as Japan and the United States.

The Pacific theatre of World War II left deep scars among Asian states, many of whom suffered brutal occupation under Japanese rule, including one of the most controversial practices–the use of comfort women by the Imperial Japanese Military. This form of human trafficking involved the coercion of women into prostitution to raise the morale of Japanese soldiers. The fundamental concern with Abe in this regard is that he’s part of the Liberal Democratic Party committee for historical investigation, a group that objects to the use of comfort women by Japan. Abe himself forced the NHK (Japan’s National Broadcasting Organization) to omit sections of a documentary regarding Japan’s actions during WW2, especially those about comfort women. His repeated attempts to alter the official government stance on comfort women have only been prevented via political pressure from Washington. These issues do nothing but antagonize Tokyo’s relations with its neighbours, especially with a rising China.

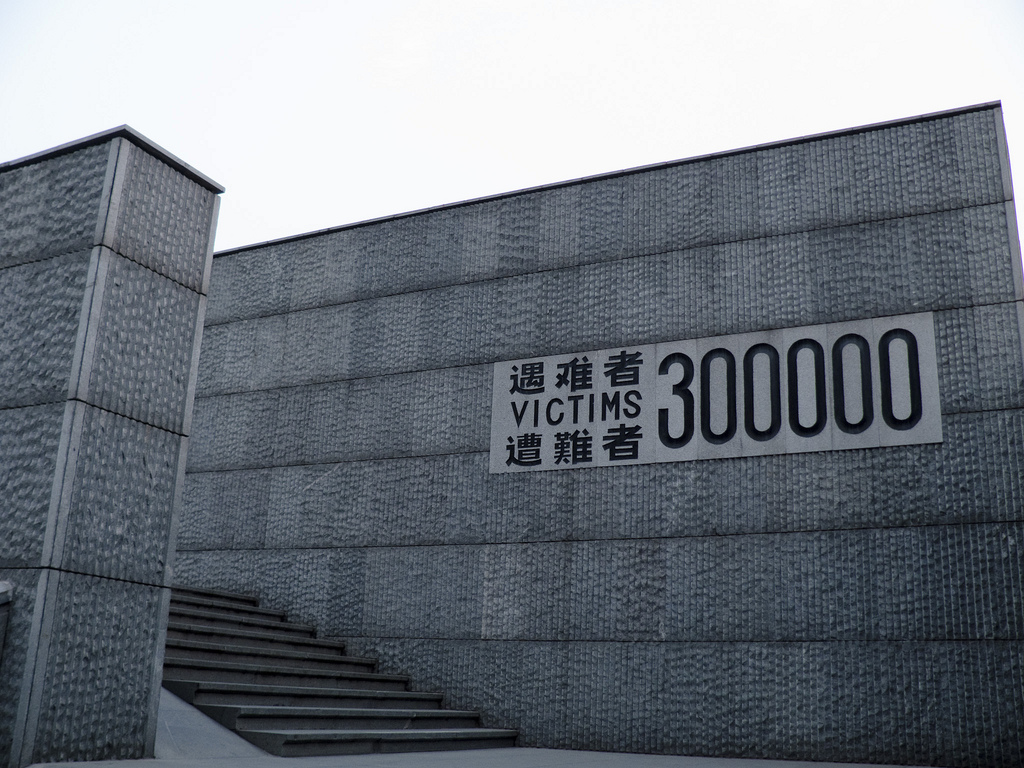

Sino-Japanese relations are tenuous. Both states remain mired in conflict over territorial sovereignty involving the Senkaku islands; new Japanese textbooks introduced in 2014 by the Abe administration even state that the Senkaku Islands are sacred Japanese soil. The Sino-Japanese rivalry is not new, as the conflict between both states stretches back 1500 years. Geography means that for many years, both nations have grappled for regional power. Resentment by both sides continues to intensify as China is increasingly angered by Japan’s refusal to confront its history of aggression, especially that of the Nanjing Massacre of over 300 000 Chinese in 1937. Meanwhile, within Japan a consensus has formed that Japan’s significant aid towards Chinese development during the 1970s was a mistake and created an enemy at the gate rather than an economic ally. This is evidenced by Japanese defence reports increasingly highlighting the growing threat of China, especially maritime forces which threaten Japan’s security, already weakened by a loss of agricultural self-sufficiency and lacking natural resources.

The Japanese 2018 Defence Budget is expected to be the highest spending in the nation’s history, with the majority of increased spending due to demands for sufficient counter-measures and interception capabilities to counter North Korea’s increasing nuclear threat. This, along with rising Sino-Japenese tensions, will ultimately lead to normalization of Japan with or without Abe at the helm.

Due to the reality of global economic interdependence, Tokyo will continually increase the operational range of its de-facto armed forces to secure energy and agricultural security and maintain protection of its sea lanes from an assertive regional rival in China. The true danger is that of a naval arms race in Asia prompted by Chinese naval expansion. A naval arms race does not necessarily lead to conflict but combined with the myriad of territorial disputes and a significant increase in naval capabilities, it may drastically raise the prospect of a diplomatic mishap. Increasingly tangible security dilemmas in the region could lead to war. Improper handling of any mishap could spiral out of control. Policymakers often simplify complex realities by viewing the situation through a strategic culture formed via national experience. Thus, Abe’s challenging of Japan’s historical brutality during the Second World War and its treatment of prisoners and comfort women means that any policies enacted will be met with suspicion from neighbouring states. George Santayana once stated, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. For Abe, failure to publicly accept and acknowledge Japan’s bloody past will lead to widespread ostracization by neighbouring states.

Japan with Abe as its helmsman will have to confront a rising China, a nation indubitably more powerful than Japan. Thus, Tokyo will increasingly need allies, but the era of American unipolarity in the Pacific has faded; Japan can no longer hedge its security solely on American military dominance. Thus, Tokyo will accordingly seek to internally balance through normalization. Yet, Tokyo’s rearmament will be challenged by neighbouring states, due in part to the perceived neglect of its historical grievances by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Rather than signal a new resurgent era for Japanese foreign policy, old grievances present in nationalistic Asian states may constrict policy decisions for potential Japanese allies, and Abe may be the herald for a twilight over the land of the rising sun.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo