The New Face of Espionage : Intelligence Tactics for the Internet Era

A power cut hits an Eastern European capital, a government employee spends their day writing comments on social media, a series of confidential files turn up on the web, and an inflammatory ad shows up on a Facebook feed. What do all of these things have in common? They’re not unimaginable events, most seem inconspicuous, and all are easy to deny as having malicious intent. Yet, these disparate actions are linked, and reflect the latest evolution of age-old strategies. This trend goes by multiple names: hybrid warfare, cyber warfare, information warfare. Each is slightly different, but all overlap and represent state intelligence agencies adapting their coercive strategies for the modern era. These strategies are multi-pronged, and they blur whatever lines between diplomacy, military, and espionage once existed– as well as the line between war and peace.

Espionage as a State Tactic

Actions that are low-cost and have a high degree of deniability, yet yield large returns, have high appeal to any actor, states included. However, military operations require the mass-movement of personnel and equipment and are costly in both human and material terms, while diplomatic activities require hard-to-build trust and a degree of mutual interests to function. Thus, states often resort to a third option, whether that be on its own, or, more often, in conjunction with the other two. This option is espionage. Spycraft as a whole is often romanticized or blown up into the notion of bold well-dressed men running around the world. Most avid spy-thriller readers will be familiar with at least one or another cultural depiction of such actors, whether that be a ladies man with a license to kill like James Bond, or a gun-blazing juggernaut like Jason Bourne. Yet, much like any cultural depiction, the reality is often quite different, and more nuanced.

Espionage can be divided into different categories of activity, from active measures -forceful actions taken to change the status quo – to more passive actions, such as the gathering of intelligence and information on the actions, capabilities, and intents of adversaries. Additionally, it can be divided into human intelligence, characterized by interpersonal interactions and the manipulation of people, and more technological forms such as signals intelligence, wherein signals and codes originating from an adversary are analyzed, intercepted or broken into. From sabotage to deceit, and theft of information to propaganda, these tools have been utilized by states for centuries. During World War 2, Allied codebreakers worked non-stop to decipher Axis plans. While during the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States never actually battled head-on – instead fighting through their respective spy agencies the KGB and CIA, and through allies and proxies around the world.

A threat to institutions

The onset of the internet era has dramatically changed previous structures– the strategies of espionage and interference utilized by states among them. More systems than ever are connected over electronic and internet-based networks, while social media provides loosely regulated access to millions of people. Additionally, physical realities that once mattered deeply like distance have ceased to be as important. Today, it is possible to instantly communicate across oceans and borders, while simultaneously hiding where you are operating from via VPN proxies. Furthermore, citizen’s attitudes have become increasingly mistrustful of others, many issues quickly become partisan, and social media companies seem incapable of stopping abuse or “trolling” on their platforms. Altogether, this has cultivated a toxic environment where it is easier for state actors to act with impunity. They can manipulate the distrust and chaos, and, if caught, they can use those same factors to undermine their accuser’s accusations, no matter how clear the evidence.

Although the targets vary, these tactics aim to pursue states’ geopolitical, economic, and ideological interests. One of the most sensitive targets is adversary’s institutions. Traditionally states had to utilize costly methods such as diplomatic isolation, economic pressure, or arming insurgencies; however, new technologies have facilitated direct access. One of the first cases of this new kind of covert warfare being used to target physical institutions was the Stuxnet virus utilized against Iran’s nuclear programme in 2009. Widely believed to have been developed by the American or Israeli government, this virus compromised computers, causing nuclear centrifuges to spin wildly out of control thus destroying them. Since then there have been increasing concerns that such an attack could be replicated on vulnerable systems such as the North American power grid. In Canada alone, between 2013 and 2015, more than 2,500 state-sponsored cyber activities per year were detected against important networks, both private and public. Furthermore, of all cyber attacks detected – both state and non-state – more than 2,000 targeted federal systems relating to natural resources, energy, and the environment.

Manipulating the public

Physical institutions are not alone in facing new threats. A recent report by the Communications Security Establishment (CSE), the Canadian agency in charge of cybersecurity and defense, details some of the ways in which less tangible institutions have been targeted by covert cyber actions. The report warns of a multi-faceted threat which has targeted elections, political parties, and politicians, on both traditional and social media. During elections, state adversaries use cyber capabilities to suppress voter turnout, tamper with election results, and steal voter information. Against political parties and politicians, cyber espionage is conducted for the purposes of coercion and manipulation, as well as to publicly discredit individuals; an action often made easier by lax cyber hygiene practices. This is a problem on both sides of the border: in June a firm linked to the Republican Party failed to password protect its data, thus exposing the personal information of almost every single US voter. Finally, the report warns that on both traditional and social media, adversaries are using their capabilities to spread disinformation and propaganda, often in attempts to shape voter’s opinions.

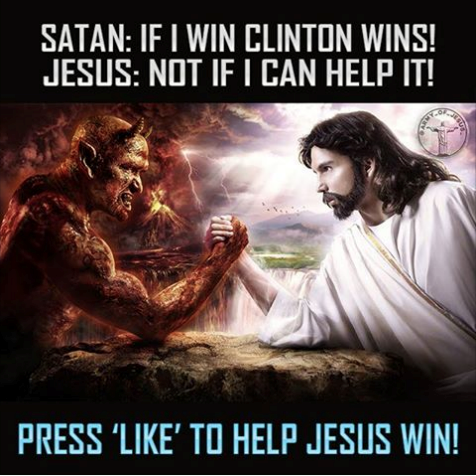

In recent months, more light has been shed on what such tactics entail. In one example of what the CIA, FBI, and NSA have jointly labeled “sophisticated interference in the US election”, upwards of 80,000 posts, and 3,000 sponsored ads were created and paid for by the Internet Research Agency, a Russian media company with ties to the Kremlin. These ads were precisely targeted using Facebook ad procedures, allowing them to reach very specific audiences. One of these ads, depicting a woman wearing a niqab and captioned “Sharia law should not even be debatable” alongside “stop all invaders” was shared upwards of 235,000 separate times. Astonishingly, the cost of sponsoring an individual ad is as low as $200 to $1,000 USD. This content covered a disparate range of topics, yet binding it all was divisive content on polarizing issues – especially those related to the election, the tendency to look professionally made and have legitimate sounding names, and a propensity for bad English grammar.

Not all of these were one-off attempts– some campaigns played out over a longer period. “The Heart of Texas” a group created in November of 2015, started off sharing only Texas secessionist, Christian based posts, before morphing into sharing anti-Clinton posts over the course of the 2016 election, then finally organizing anti-immigrant rallies. Finally, this past September, it was discovered by Facebook and shut down. Another campaign titled “Don’t Shoot Us”, was cross-platform, operating on Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Youtube, and even Pokemon Go. Among other activities, in July of 2016, it encouraged followers to visit the sites of police shootings and name Pokemon caught there after the shooting victims. Presumably, the intent behind these groups was that in utilizing the imagery of existing causes, sharing graphic and divisive content, and inciting followers to action, domestic tensions could be stoked. Facebook estimates that 29 million Americans saw posts generated from groups directly run by Russia based operatives, and that they may have reached up to 126 million American Facebook users. In total, 470 Facebook and 201 Twitter accounts linked to the Internet Research Agency have been shut down over the past several months.

Although social media companies have come under fire for failing to notice or act on these posts, especially considering conspicuous details such as all payments being made in Russian rubles, this threat is only part of a wider series of vulnerabilities linked to U.S democracy. Over the past two years, electronic voting systems in at least 21 states – including key battlegrounds – have been targeted – and in the State of Georgia, voter data which could have provided evidence of system compromising was mysteriously deleted. The previously mentioned CSE report contains a sobering note on such trends; warning that they believe it is “highly probable that cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide will increase in quantity and sophistication over the next year, and perhaps beyond that” given the “dynamic of success emboldening adversaries to repeat their activity, and to inspire copycat behaviour.”.

A New Era

Espionage, hacking, and spycraft are often thought of as things that are far away, and directed at entities well above the average Joe. This is clearly not the case. Tactics being embraced by states may seem absurd when compared to our cultural notions of a hacker crouched over a computer, or James Bond sipping on a martini on the roof of a casino. However, social media and the global web have created a newfound ease in targeting active measures at large audiences and key institutions, while greatly reducing such strategies’ cost. Pressure is rising on social media companies to regulate and monitor their platforms, and governments are scrambling to update the security of key systems against possible attack. Yet as long as such covert actions are cheap and easy, and a high level of distrust remains to manipulate and hide behind, this trend will continue. The internet has brought many new things to the modern world by changing the nature and ease in which we interact. The world of espionage, propaganda, and state intrigue has caught up to this reality, and if institutions are to remain secure, those with stakes in them should too.

This article has been edited by Sarie Khalid