Slavery – Not an Institution of the Past

Example of a Thai fishing ship. Men from neighbouring countries may be trafficked as labour to work on these.

http://bit.ly/2hqsgi3

Example of a Thai fishing ship. Men from neighbouring countries may be trafficked as labour to work on these.

http://bit.ly/2hqsgi3

Currently, every country around the world has abolished slavery, though the final country to do so was Mauritania, only a few decades ago, in 1981. It would seem, as taught in modern history courses, that slavery is an institution of the past, that our global society has become enlightened by the absurdity of owning other people. This notion could not be farther from the current truth. Slavery is well and alive today, worldwide, in nearly every country, including the “land of the free”, the United States. Today, slavery takes on a variety of forms and is largely controlled by private sectors rather than the public, though state-sanctioned slavery still prevails. Worldwide, 40 million people are currently slaves in some form. The victims range from children, who comprise 25% of the demographic, to women, who in the case of sex slavery, comprise 99% of the victims, to whole families bound by traditions of debt bondage. Then why is it that despite this, we fail as a global society to recognize slavery as a pervasive problem affecting all people? Why is it that we even fail to recognize the notion that slavery today exists and is a thriving industry?

Only second to the drug trade, modern day slavery is the most profitable criminal activity worldwide. Yet, despite its global prevalence, it lacks a core definition: In fact, there is no legal recognition of “modern day slavery”; rather this is used as a broad term to describe different forms of human exploitation and violations. This past September, the International Labour Organization and Walk Free Foundation, in partnership with the International Migration Organization, released an extensive report titled “Global Estimates of Modern Slavery”. It organizes the phenomenon into two broad aspects – forced labour and forced marriages. Forced labour encompasses a wide net of slavery forms including sex slavery, child labour, debt bondage, and state-imposed slavery. Meanwhile, forced marriage is the event of a marriage that occurs against one party’s will, though this may be used as a guise to allow for forced labour and sexual exploitation. The report reveals the shocking international prevalence of slavery, and even then, it recognizes that the numbers and figures are only “conservative” estimates.

Additionally, slavery today is a difficult concept to navigate, as the variety of forms may vary largely by geographic location. For example, in the United States, there may be fewer cases of debt bondage, but human and sex trafficking is still a massively profitable industry. Whereas Africa is said to have the most slaves, the greatest amount of forced labour slaves are found in the Asia-Pacific region. Furthermore, the duration of someone being used as a slave may be short-term or for life, which makes it difficult to understand and gather data on the matter. Currently there are estimates of 40 million slaves, though over the past 5 years, there have been about 90 million victims of slavery.

What does slavery look like across the world?

In Thailand, we find forms of modern day slavery that follow uncannily similar patterns to historical realities. Thailand, which is one of the largest exporters of seafood, exploits men from neighbouring countries to do labour on their fishing ships.

http://bit.ly/2hqsgi3

This includes commonly coercing and/or trafficking the men into a job in which they would expect pay and relative freedom. Once they arrive however, the organizers often send these men to sea for months at a time, with constant threats of torture, or even being thrown to sea if they do not comply. And of course, all without pay. Officials in Thailand attempt to stop these injustices, though the system in place is questionable and mediocre at best.

In the riches and all-inclusive hotels and malls in the Middle East, tourists often don’t realize the extent to which forms of forced labour is ingrained in the society. With events such as the World Cup 2022 in Qatar, the harsh and inhumane conditions suffered by migrant labourers have become more prevalent. Most often, these workers are brought from foreign countries, commonly from other parts of Asia, and are subjected to a variety of dangerous projects in the region, commonly for large-scale construction projects, such as the stadiums for the World Cup. Common abuses include working under intense heat conditions, having passports taken away, receiving no pay (despite being in debt to the smugglers), and living in abysmal living conditions, often crammed with other workers. Labour laws in these countries do very little to protect these people, who thus become trapped in the forced labour industry.

Child labour is most prevalent in Africa, which commonly exploits children in the agricultural sector. The issue of child labour is such an integral and critical matter that the International Labour Organization has a separate report to navigate the specific matter. A report based on data from survey research conducted at Tulane University outlines the exploitation and abuses of child labour that occur in the cocoa industry in West Africa.

The cocoa industry is a major hub for child labour.

http://bit.ly/2ySpkCv

These children often engage in hazardous work such as land clearing (involving the cutting of trees), the burning of fields or bushes, carrying of heavy loads, and using dangerous equipment such as machetes and long cutlasses. The issue of child labour is one of the most difficult to navigate as it often occurs in the family unit or is seen as integral for survival in a society, and thus provides a unique set of challenges to overcome, however is immensely important as subjecting children to forced labour has major implications on their education, development, and by extension, society as a whole.

In the United States, slavery is very much prevalent and is evidence of systemic gender inequality, as it exists mainly in groups of women and girls through sex trafficking. Much like other forms of slavery, being coerced into such a lifestyle by the traffickers is typically how the cases begin. Once in the sex business, it is always difficult to escape, as traffickers not only use violence and abuse techniques to control these women but also exploit the fact that prostitution is illegal. Major American cities, such as Atlanta, are hubs for this kind of organized crime, which happens right under the noses of authorities each day.

Although still a clear violation of human rights, some cases of slavery might not be as dramatic as the instances quoted above. In the United Kingdom for example, there have been multiple instances where people were trafficked from countries, commonly from Southeast Asia, and brought to the UK with the promise of a better lifestyle, only to be trapped in a forced labour contract of sorts. Essentially, during the trafficking process, the victims were immediately put in debt over transportation costs by the traffickers. Upon arrival at their work locations, which included mundane placements such as nail salons or car washes, these victims were paid below the minimum wage and forced to hand over their earnings to the traffickers. Further, some worked 12 hour days, seven days a week. For a nation that has labour laws that are supposedly enforced, this type of industry is far from appropriate.

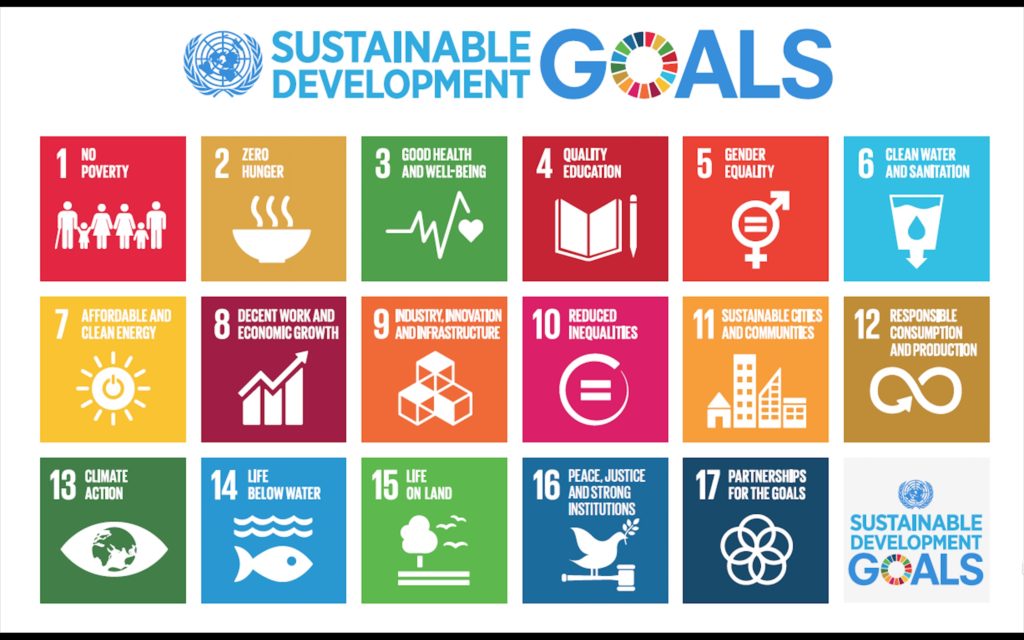

Given the atrocity of slavery detailed above, it comes as a relief that at least one solid initiative to end it is currently being exercised: the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) brokered in 2015.

http://bit.ly/2ABZdwQ

The goals are rather broad – one of its targets being “to take…effective measures to eradicate forced labour and modern day slavery and human trafficking”. Despite the lack of focus, one can easily see how it permeates into other SDG goals, particularly, the goals of quality education, gender equality, reduced inequality, peace, justice, and strong institutions. It is thus integral to take on an approach that would benefit the multiple layers imbedded in the matter. Particularly, if we are to reach the ambitious goals of eradicating child labour by 2025 and to reach “full and productive employment for all” by 2030, we should be doing more than allowing the status quo of slavery to proceed.

Conclusively, it seems that modern day slavery is an extremely profitable business making billions of dollars in profits. Clearly, it is neither a random nor an exceptional event; rather, it is prevalent and widespread. Like all forms of historical slavery, the kind we see today is a universal event and should thus be treated as such. While protecting national sovereignty is important, committing to upholding the values of proper and humane quality of life outweighs that precedent. Slavery has become, now more than ever, a force in the global economy, and means to abolish it should thus take on a global approach as exemplified by the SDGs. Until it is no longer present in nearly every country of the world, it is integral that we all take a stance on eradicating forms of ownership, exploitation and discrimination that define slavery today.

Iman Lahouaoula is a fourth year honours psychology student at McGill University.

Edited by Shivang Mahajan