Remembering 1917: Russia’s Modern Counter-Revolution

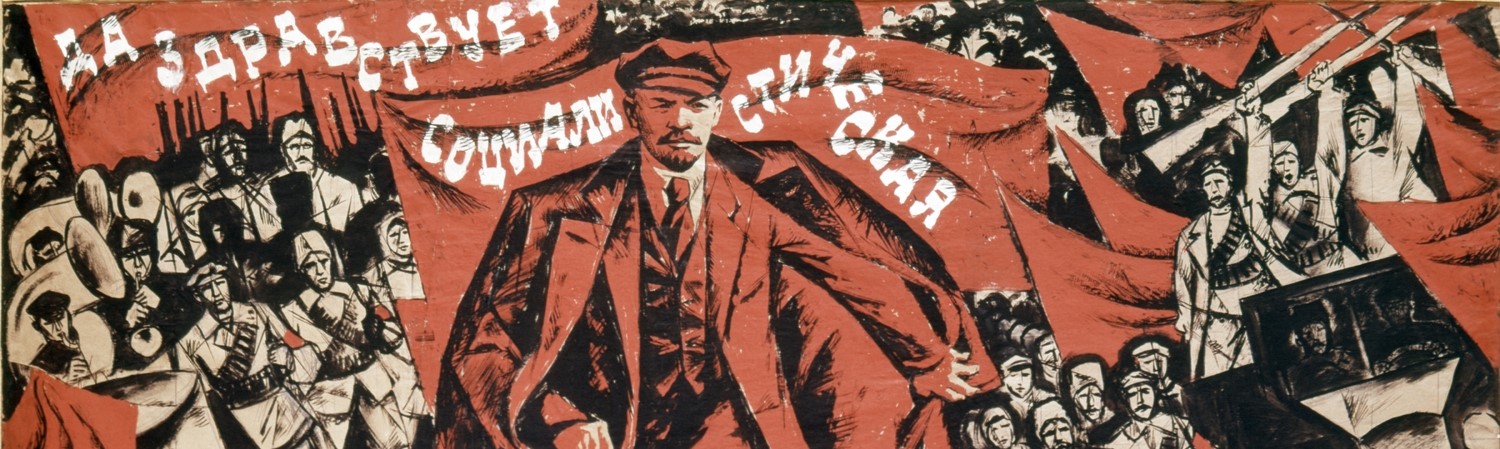

On November 7, 2017, Marxists around the world celebrated the centenary of the world’s first successful socialist revolution. In Moscow, thousands of Russian partisans marched the streets, joined by comrades drawn from the world at large. It was on that day in 1917 that Vladimir Lenin’s Bolshevik Party took control of the Imperial capital of Petrograd, effectively bringing an end to Russian provisional government established earlier that same year. By 1918, the Tsar Nicholas II was dead. By 1920, the worker’s councils (Soviets) had prevailed in a bloody and protracted civil war against a coalition of liberal democrats and tsarist loyalists. For 7 decades, Marxist ideals would stand as a force to be reckoned with within Russia and globally, until the collapse of Lenin’s revolutionary project in 1991.

However, the centenary of the revolution received little fanfare from the Russian government. What official celebrations occurred on November 7th did little to honour the memory of the 1917 Revolution. Rather, state-sanctioned demonstrations recreated a historic military parade that occurred on November 7th, 1941, in which Red Army Soldiers marched directly from the Red Square to the front line. Russian President Vladimir Putin did not attend even this tangential celebration.

Ruling over the remnants of Lenin’s shattered empire, Vladimir Putin has been described by Russian politicians on both sides of the aisle as a “21st-century tsar”. Since assuming the office of president in 2000, maintaining domestic stability has been the rule of the game for Putin – often like the Tsars and Bolsheviks before him, by any means necessary. As a guiding principle of his government, Putin has often avoided any major reform, lest it lead to civil unrest. Nationalism both abroad and domestically has also been one of Putin’s most important tools: restoring a sense of national pride through an aggressive foreign policy in Chechnya, Crimea and Syria.

Putin has also maintained stability in Russia via a system of patronage between state institutions and the financial elite. Emerging from the chaos of the 1990s, a unique oligarch class rose in Russia. Profiting off a Yeltsin-era scheme of granting shares in state enterprises in exchange for low-interest private loans, a privileged few, lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time, became incredibly wealthy. Early in Putin’s leadership, it was feared that the oligarchs would challenge the power of he presidency. Today, the state has struck a deal with the elite, guaranteeing their investments and monopolies in exchange for staying out of politics and supporting the president. This symbiotic relationship has not only guaranteed Putin’s grip on power, but has made him incredibly wealthy. Some speculate that he has now become one of the wealthiest oligarchs of all, with a net worth approaching 40 billion USD.

Like the Boyars (Russian aristocratic nobles) of old, current oligarchs lead lavish lifestyles. Many own multiple homes, both in Russia and abroad. Private airplanes and expensive custom-designed yachts seem to be common fare amongst Russia’s elite. Predictably, many of these oligarchs stash their incomprehensibly large fortunes in off-shore accounts, sheltering themselves from taxes. Despite Putin’s promises of stability and economic growth, however, benefits have not trickled down to all Russians. Inequality between Russians is at an all time high. According to international financial institution Credit Suisse, inequality in Russia is in a class of its own, incomparable to other developed economies. Today, Russia’s 111 billionaires control 19% of all Russian household wealth. On a wider scale, the top 10% of the Russian population controls 87% of the nation’s wealth. Ironically, despite promises of reform and liberalisation, inequality is higher in Russia today than it was at the time of the revolution. With a growing tide of global populist uprisings, at their core based on income disparity, it would seem Russia’s oligarchs have much to worry about.

It is, therefore, unsurprising that celebrations of the revolution have been muted, at best. The Russian government has acted as though in fear of triggering historical déjà-vu amongst the state’s economically dispossessed. With over 50% of Russians believing the collapse of the Soviet Union has had largely negative consequences for their society, this fear is not entirely unfounded. Coupled with Putin’s emphasis on stability, it is clear that celebrating a revolution that toppled an autocratic regime would have been tragically short-sighted. In addition, it would also have been seen as counter-intuitive to Russia’s foreign policy, much of which has been focused on preventing anti-Russian “colour revolutions” in former Soviet Republics.

Nonetheless, Putin’s popularity remains at an all time high. 87% of Russians are confident in Putin’s leadership on the world stage. This rating is highly correlated with Russians’ perspective on the economy however–those least satisfied with their financial condition are likely to rate Putin lower. Despite this, 58% of Russians are satisfied with the direction of their country. Although the anxieties of populist revolt are real, support for political opposition remains low. In the 2016 Russian Parliamentary elections, all major parties lost seats, save Putin’s United Russia, which won in 105 new jurisdictions. Russia’s modern Communist Party, now the main opposition, lost 50. With Russia’s Presidential Election around the corner in 2018, it is likely that Putin’s grasp on power will hold, despite no official announcements yet of his intention to run. Thus, in the short term, divergence from the status quo seems unlikely.

The Soviet Union was a state with many flaws. Full Communism was never achieved. Instead of the state “withering away” as Lenin predicted, a stagnant and ineffective bureaucracy persisted until the USSR’s demise. This mismanagement of a centralised economy ensured wide-scale economic disenfranchisement. In sum, Lenin’s revolution failed to live up to the promise of full equality. In the same breath, Russia’s 1991 undertaking of political liberalisation fell short of its potential. The country today now demonstrates many of the worst excesses and stereotypes of an economic system Lenin sought to destroy. With Putin’s grasp on power stronger than ever, the prospects for change seem bleak. However, if anything can be learnt from 1917, it is that a people can only tolerate their oppression for so long. With widespread efforts to suppress its memory, it is likely that Putin thinks so too.

Christopher Ciafro is a second year McGill student, completing an Honours Degree in Political Science.

Edited by Luca Loggia