South Africa’s #BlackMonday Protests Suggest that Recent Farmer Deaths Indicate “White Genocide”

Johannesburg's Apartheid Museum hands out these passes to visitors; though intended as historical relics, the racial divisions between South Africans today mirror the Apartheid era. https://flic.kr/p/9DU1K

Johannesburg's Apartheid Museum hands out these passes to visitors; though intended as historical relics, the racial divisions between South Africans today mirror the Apartheid era. https://flic.kr/p/9DU1K

On October 30th, a procession of trucks, tractors, and farmers dressed in black lined South Africa’s roadways. The protestors, a majority of whom were white, gathered to voice outrage at the uptick of “farm murders” in South Africa and to demand state action. At least that is what organizers Talita Basson and Daniel Briers intended, citing the death of farmer Joubert Conradie as the inspiration for the “Black Monday” protests which aimed to join mourners together in solidarity. Unintentionally, their slogan “enough is enough” was shortly taken up by South Africa’s white minority. White supremacists protested that they had had enough of “white genocide”; the attacks, according to them, were part of a government conspiracy against white farmers. They advocated a return to Apartheid, using eerily similar rhetoric to alt-right protests during Donald Trump’s presidential campaign, and evoked comparable sentiments of white victimhood. However, like the American historical context, racial tensions created conflict in South Africa before international media realized that the country had a white supremacist problem. Institutionalized racism and power imbalances were clearly not solved by South Africa’s independence. The racial superiority complex of many white settlers, coupled with the fear that their power is waning due to economic decline and affirmative action policies, blinds them from recognizing black suffering, just as their socio-economic privileges they’ve retained since Apartheid similarly obfuscate their view.

In response to the protests, Zizi Kodwa, the former South African presidential spokesperson, wrote a widely-circulated letter to Basson and Briers, in which he commended their “genuine concern of farm killings” and lamented the “racial polarisation and blatant display of bigotry” that sabotaged the demonstration. As a result, the protests kick-started an international debate over the existence of white genocide and white privilege as #blackmonday trended on Twitter. The conversation got especially heated when AfriForum, an organization representing white South Africans, declared that white farmers were “almost five times more likely to be murdered than the general population.” Their “statistics,” however, were quickly disputed by the fact-checking organization Africa Check, which stated that “white people in South Africa are less likely to be murdered than any other racial group.” In fact, black males are the most vulnerable group, according to the Governance, Crime and Justice Division of the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies. The Divison’s head, Gareth Newham, affirmed that “[white people’s] concerns are serious,” but that “they think it’s only them and this is a mistake.” Furthermore, it is nearly impossible to find exact statistics regarding farm murders, as the police do “not keep specific statistics about farm killings,” let alone the killing of farmers by demographic group. Disproportionate media representation also affects what data are readily available. Attacks on a white farm owner, with acres of land and many workers, are more likely to grab news headlines than violence against one of his many black “servants” who are vulnerable to attacks inside and outside their farms. Newham suggests it’s thus unproductive to search for exact statistics and advises people to “appreciate it’s a national issue” that affects both black and white farmers.

Though black and white individuals have both been affected by South Africa’s steady increase in violent crime, their resistance efforts have been met with differing degrees of police brutality. Contrary to AfriForum’s suggestion that the state prioritizes the demands of black people, the police response to #blackmonday revealed that power imbalances favour white settlers. The police did not clear the roads, and no stun grenades or rubber bullets were fired. This may have been different if the protesters were black. During a 2015 student protest, for example, black students were “beaten by the police, shot with rubber bullets and trampled on” while “white student protesters moved freely […] with no one touching them.” The contrasting police responses reveal underlying perceptions of black people as dangerous and violent, showing the persistence of Apartheid-era stereotypes.

This institutionalized racism has led white supremacists to pin “black aggression” as the root of South Africa’s problems, thus motivating their desire to “go back to the good old days.” During Apartheid, white settlers had total control over the country’s economy and enjoyed unmitigated exploitation of black workers. Now, as South Africa faces economic decline, some white farmers want Apartheid back. Affirmative action policies and social services “threaten their privileges,” leading white farmers to “feel racially persecuted despite their relative wealth.” Their so-called “isolationist victim mentality” stems from the feeling of racial superiority and the fear that their power could imminently be taken away. White supremacist Ernest Roots outlines this seemingly contradictory mindset as he suggests that his race suffers most from South Africa’s economic decline but is also responsible for the country’s wealth. “The unique frequency of the murders, the unique levels of brutality, the farmers’ huge role in the country […] means that [white] farmers need more protection,” Root said, suggesting that white farmers require special treatment as a result of their economic position. He fails to recognize the economic impacts on the country’s majority population —black farmers earn an average of R1500 (US$110) a month— which also suffers from the country’s wage gap due to the structures of inequality that Roots upholds through statements like this one. While racial violence is clearly seen by South Africa’s black population as part of their daily reality, many white South Africans are blinded from seeing these structures as result of their privilege.

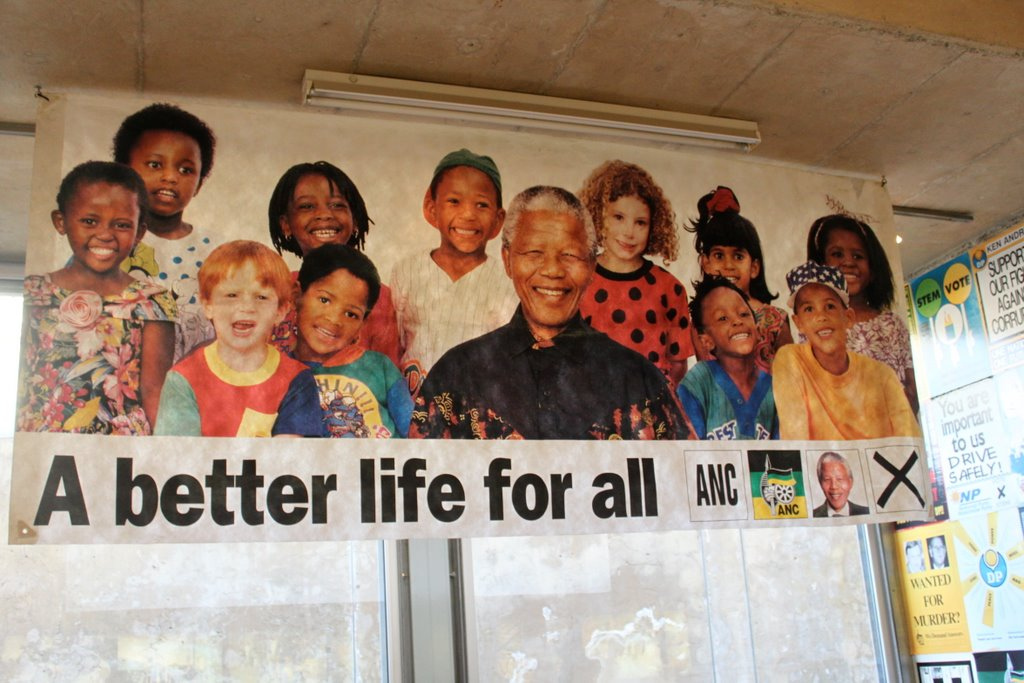

At the dawn of South Africa’s independence, the debate over whether white genocide, or white privilege, affects white South Africans would seem unthinkable to an international audience. The “rainbow nation,” symbolized by Nelson Mandela, was depicted as a diverse yet unified country. During celebrations of the new nation’s emergence in 1994, however, structures of Apartheid lurked under the surface. More than two decades after independence, racial tensions in South Africa have only recently been brought back to the international spotlight. The discourse of white victimhood has also been a recent phenomenon in the United States and emerged from similar rhetoric as used by the alt-right’s South African counterparts.

When slavery was eradicated after the American Civil War, white Americans lamented the loss of worker exploitation and were forced to compete within a society in which all citizens were equal under the Constitution. Thus, many white Southerners held onto pro-slavery sentiments. Investigative journalist Robert Parry writes that “Confederate apologists insist that slavery wasn’t really all that bad for blacks [and] that the Civil War was really just about differing interpretations of the Constitution.” The lack of recognition of past wrongs has led many Southerners to feel that they, in fact, were the victims in this “war of Northern aggression,” because the prior socio-economic structures were favourable to them. The isolationist victim mentality was clearly alive and well even before the slogan “make America great again” turned Trump supporters to nostalgically look toward America’s past. Trump’s rhetoric stoked fears of those who felt their historical racial superiority was endangered by “demographic and sociopolitical change.” South Africa’s protests, advocating a similar turn backward, saw posters saying “no Boer, no Pap” —suggesting that, without Dutch-descendant farmers, there will be no porridge to eat— as the Apartheid anthem sounded in the background. Furthermore, a fundraising campaign was created to send Steve Hofmeyr, a white South African singer and alt-right “crusader,” to the U.S. to meet with Trump. The global solidarity between South African and American white supremacists exemplifies how “white victimhood” is further legitimized, normalized, and mobilized worldwide as world leaders dabble in right-wing populism.

Since South Africa’s independence, many believe that racism is increasing across the country. A decade ago, 70 percent of white South Africans said that “Apartheid was a crime against humanity.” This year responses dropped to 53 percent. TED speaker Sisonke Msimang declares that “post-apartheid South Africa has become imprisoned by its own past — a past which whites cannot recall and which blacks cannot forget.” Thus, the use of sporadic violence against white people —justified by the desire for some black South Africans to secure reparations for the racial violence they received under Apartheid— is not to be tolerated either. The far-left is not without blame in their response to the #blackmonday protests. Tweets celebrating the deaths of the white farmers for getting payback for Apartheid display how history has been mobilized by both sides of the political spectrum in this debate.

Rhetoric promoting a “focus on diversity” is often advocated for when trying to resolve racial tensions in South Africa. However, Msimang cautions us against this focus’ implications: “too often, the immediate preoccupation is with ensuring that white South Africans still feel welcome […] so ‘diversity’ becomes a way to reassure whites of their place in an otherwise black country.” When it is used to evoke unity by suspending discussion of difference, diversity-based rhetoric can oftentimes do more harm than good. It is imperative to recognize that issues of violence in South Africa leave both black and white individuals vulnerable, but it is also important to recognize differences created by systems of power and historical legacies. Thus, one must pay attention to how race and class shape the way violence is wielded and experienced. Moreover, there must be a simultaneous recognition of Apartheid’s effects today, while also seeing the current moment as separate from the past, with different power dynamics that have yet to be analyzed.

Edited by Jason Li