An Olympic Bargain: Engagement and Socialisation of North Korea

Joint Korean Olympic team at the Sydney Olympic Games.

Image retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yd3z5l47

Joint Korean Olympic team at the Sydney Olympic Games.

Image retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/yd3z5l47

On January 9th, 2018, the Inter-Korean talks between North and South Korea rendered some of the brightest prospects for peace on the Korean Peninsula in years. The representatives at the talks announced that North Korea would participate in the upcoming 2018 Winter Olympic games hosted by the South. They further agreed to reinstate a military hotline between the two states, marking a sudden cooling of tensions on the Peninsula. Although talks of engagement began in 2017, official talks stemmed from January 1st, 2018, when Chairman Kim Jong-Un of North Korea declared the completion of his government’s nuclear deterrent. This New Year’s pronouncement follows a decade of international sanctions, condemnation, and rhetoric fuelled tweets from the incumbent President of the United States (U.S.), Donald Trump.

Calculated Diplomacy?

Chairman Kim Jong-Un’s declaration, in conjunction with the successful test of the Hwasong-15 Inter Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) on November 19th, 2017 places the territorial breadth of the continental United States of America within range of Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal. Indubitably raising Washington’s ire, along with Pyongyang’s declaration during recent inter-Korean talks that their nuclear arsenal was “only aimed at the United States, not our brethren [South Korea], China or Russia”. The inter-Korean talks in question were prompted by a rare offering of an olive branch during Chairman Kim Jong-Un’s New Year Speech in which he expressed and extolled his wishes “for a peaceful resolution with our southern border”, and offered bilateral talks with Seoul to discuss Pyongyang’s participation in the upcoming 2018 Pyeongchang Winter Olympics hosted by South Korea. This rare offer was enthusiastically accepted by South Korean Prime Minister Moon Jae-In, whilst plans are now underway for Seoul to receive a North Korean delegation at the 2018 Olympics. As of January 17th, 2018, another optimistic agreement was made to march under a unified Korean flag at the Winter Olympic games.

These agreements signal an opportunity to engage with, and socialise North Korea into the international community. For starters, Pyongyang has not been deterred from its nuclear program by previous sanctions and global rhetoric. It is most likely developing nuclear weapons to attain a balance of power against its disadvantaged asymmetry of information and material capabilities vis-á-vis Seoul, Washington, and Tokyo. The case might be that Pyongyang feels threatened by the U.S’ powerful presence in Asia with 28,500 American troops stationed in South Korea, 50,000 alike stationed in Japan, and American naval power positioned so as to have North Korea within range. Moreover, one should recall that the Korean War is still ongoing as its cessation was due to an armistice, not a formal peace treaty.

The North Korean regime is not an irrational actor which will suddenly launch a nuclear attack on the U.S. without due reason, as the regime foremost seeks its own survival. Pyongyang thus believes survival is best attained through the complete maturation of its nuclear deterrent. It is noteworthy to imagine how a senior North Korean official might observe its security position given U.S. driven provocative activities such as joint annual war-games by superior US-South Korean armed forces, flight drills by US nuclear bombers near North Korea, and tweets by the incumbent US President warning Pyongyang of meeting with “fire and fury“. Provocative developments, in turn, met by Pyongyang’s own reprisals, calling US President Trump “A dotard“, warning of a grave provocation by joint air drills in December 2017 could be met by nuclear retaliation.

Deputy to North Korea’s Supreme People’s Assembly Ri Jong-Hyok stated, “It’s [the] Korean people’s resolute decision that [North Korea] should face off the U.S. only with nuclear [weapons] to achieve the balance of power […] any country in the world need not worry about our threats as long as they do not join invasion and provocations toward us”. It is highly probable that Pyongyang is seeking to drive a wedge between the U.S. and its Asian allies, especially South Korea, via bilateral negotiations with their Southern brethren. Pyongyang, backed by the maturation of its nuclear deterrence program, entered these talks with the strongest position in its history, especially with the onus of the upcoming 2018 Olympics lingering over the Korean peninsula.

Stability-Instability Paradox:

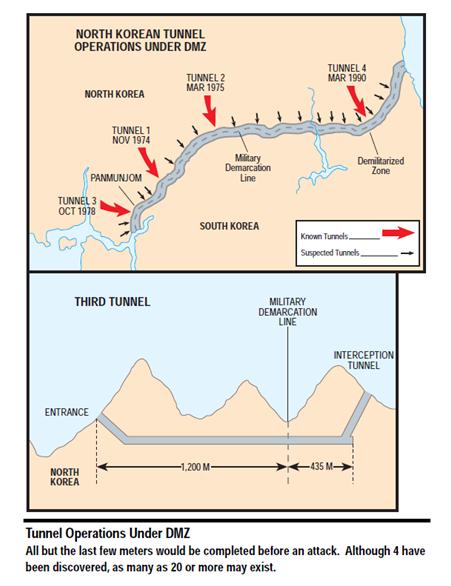

A precarious situation exists on the Korean peninsula as North Korea may be emboldened under the Stability-Instability paradox to engage in low-intensity conflict/raids against South Korea so as to ratchet up the pressure to force further negotiations. The paradox refers to how nuclear weapons provide stability by deterring major interstate conflicts whilst facilitating low-intensity conflicts under the protection of a nuclear umbrella. The existence of a vast labyrinth of tunnels under North Korea, some of which have entered South Korean territory is even more alarming, as it could serve as an open route for low-scale conflicts, cornering Seoul onto the negotiating table. Seoul is placed in a particularly precarious position as a result, as such low-intensity conflicts would surely jeopardise its economy, whilst being unable to strike back due to fear of nuclear retaliation.

Image retrieved from U.S. Department of Defence Report.

Further international sanctions will not force Pyongyang to relinquish their coveted nuclear arsenal, the fruit of nearly two decades of progress. Sanctions will only further ostracize Pyongyang, whose increasing isolation will surely prompt an entrenchment of its nuclear deterrence against its fears of external intervention. Nor is violent regime change preferable, as such an event may lead to rogue nuclear development as the central government loses control of its nuclear arsenal during a domestic struggle, drastically increasing the possibility for a nuclear mishap. While Pyongyang’s intentions for its recent willingness for open dialogue are not fully understood, it signals a rare opportunity for North Korea to be engaged with, and begin the process of its socialisation into the international order.

International Precaution

The international society should utilise the 6 Party Talks between China, Russia, United States of America, Japan, South and North Korea as a framework upon which to continue to engage North Korea – initially to sign a formal cessation of the Korean War, then gradually negotiate with Pyongyang to assuage its fears over regime survival. The alternative is a continued game of nuclear chicken between North Korea and the U.S., each successive bout only raising the stakes, with few mechanisms to cool tensions.

An ancient Greek proverb states “After the war is over make alliances”. In essence, cordial relations should be developed between belligerent states to prevent a relapse into conflict. In Korea this has not occurred; a brief stint with South Korea’s Sunshine Policy of engagement with North Korea ended in failure as Pyongyang’s underlying fears over regime survival were not addressed. Yet, this failure must recognise the policy’s successes with increasing inter-Korean relations through the Kaesong industrial complex, a joint industrial site, increasing cross-border tourism, and even state visits between then Chairman Kim Jong-Il and South Korean Presidents Kim Dae-Jung and Roh Moo-hyun. Perhaps now, with the maturation of their nuclear arsenal Pyongyang’s fears can be put to relative rest. Its recent overture for dialogue may signal a rare but fleeting opportunity to engage with North Korea, and socialise it into the international society over the ensuing decades.

Edited by Arnavi Mehta