Canada’s Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Question of Consolidation

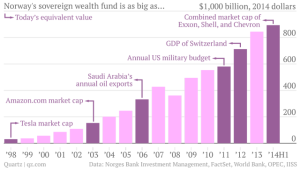

It is a well-established fact that Norway has a massive sovereign wealth fund (abbreviated “SWF”) from its oil resource, totaling US$893 billion; other oil producers such as the U.A.E. and Saudi Arabia have sizeable SWF’s as well, valued at $773 billion and $757 billion each [1]. However, it might come as a surprise that Canada also has a sovereign wealth fund; Alberta’s Heritage Fund which was built from Alberta’s oil income has a portfolio of $17.5 billion [1].

Now, $17 billion is a large sum of money. In comparison with the SWF’s of Norway or other oil producers, however, it is a paltry amount. Considering that Alberta’s fund was created fourteen years prior to that of Norway’s (1976 for Alberta and 1990 for Norway), it is rather shocking that Alberta’s fund is so small. In its nascent years, Alberta’s fund received 30% of non-renewable resource revenue received by Alberta’s government; later, it was reduced to 15%, and then discontinued altogether in 1987 [2]. In other words, no contribution has been made from non-renewable resource revenue for the past twenty years. Peter Lougheed, the former Albertan premier who set up the fund, commented that “the fund would now be worth $100 billion” if his original contribution plan had not been changed by future government policies [3].

Due to the fact that most Canadian provinces collect considerable revenues from non-renewable resource sectors such as oil and mining, there exists SWF’s in other provinces. The Quebec Generations Fund, created in 2006, stands at $5.9 billion and is comprised of funds received from a portion of Hydro Quebec’s revenues [4]. In addition, British Columbia published plans for its British Columbia Prosperity Fund in 2013 to save a portion of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG); the BC government projects that it will save about $100 billion from LNG revenues over the next thirty years [5]. Even Northwest Territories has created a structure for its own SWF [6].

There are many reasons why Canada requires such SWF’s. First, Canada’s resource-based economy is strongly influenced by commodity booms and busts. The present decline in oil price serves as an excellent example of a bust. Alberta’s premier Jim Prentice has already warned Albertans of impending cuts to services due to lower oil revenues [7]. In such instances, income from a large SWF can be used to stabilize government revenues. Second, the benefits of non-renewable resources need to be felt both by present and future generations. If all revenue from the resources is spent on current consumption, there will be no benefits left for future generations once the resources are depleted. Savings achieved through SWF’s allow for intergenerational equity and prosperity of Canadians in the future. Third, the fund can be used to achieve certain objectives deemed just and equitable. For example, Norway uses its funds to invest in green technology; the fund has announced that it will “accelerate investments in renewable energy, waste management and energy-storage companies” [8]. Norway’s fund also creates a blacklist of companies that it does not invest in because of the companies’ harmful activities, including environmental damage, labor rights infringement, military production, and more [9]. However, this third point must be taken with caution; the fund’s immense capital can be used as a political tool as well. For one, Norway has blacklisted two Israeli companies related to construction of settlements in West Bank [10]. Exercising political power through SWF’s is a question that the Canadian public will have to answer.

Now is a good time to discuss how Canada can strengthen its SWF’s, given that several Canadian provinces and territories are in the process of creating one for themselves. Consolidation of the provincial SWF’s is necessary to ensure that the fund has a clear mandate, transparent and autonomous governance, and the ability to include more provinces and territories over time.

First, a consolidated SWF is necessary to ensure that the fund has a clear mandate. Currently, Alberta and Quebec’s funds are managed by their respective provincial pension funds; Alberta Investment Management Corporation manages Alberta’s [2] and Caisse manages Quebec’s [4]. Given the relatively small amount held by the SWF’s, it is acceptable that pension funds are managing the province’s SWF. However, as the SWF grows in value, this will also become increasingly difficult, because SWF’s have different investment mandates from pension funds. While pension funds have stable inflows and outflows comprised of employee contributions and pension payments, SWF’s have large inflows in years of active mining/drilling with little outflows. However, when the resource is depleted, the inflows stop altogether. In other words, while pension funds can be easier to sustain in the long term (increase contributions if necessary), the same cannot be said for SWF’s. Instead, the SWF must maximize its value before the resource is depleted so that the returns from the fund are substantial enough for future generations. As such, SWF’s need to have clear mandates to create an immense portfolio that will be highly profitable for future generations. To best achieve this, an SWF needs its assets to be managed by an institution entirely pledged to this goal. Since the individual provinces’ funds are too small to justify the costs of having independent investment institutions, the provinces should come together to create a consolidated sovereign wealth fund.

Second, a transparent and autonomous governance of SWF can be achieved through consolidation. The governance of the consolidated fund will be entirely independent from politics, much like the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board. CPPIB remains accountable to the federal government, but has Board of Directors separate from the government. This structure has protected CPPIB from harmful interventions from the federal government. Likewise, the consolidated fund must remain accountable to participating provinces, but with an independent governing body. This structure of fund management, coupled with the fact that it is no longer a provincial institution but a multi-provincial one, will ensure that the consolidated fund will not be susceptible to political changes. For example, a populist governing political party of a province will not be able to make substantial changes to areas such as the structure of the fund or the percentage of contribution from royalties. This will protect the fund from sabotage, which unfortunately happened to Alberta’s provincial fund.

Third, the consolidated fund’s existence will encourage provinces without an SWF to create one and join the consolidated fund. Most provinces and territories do not have an SWF because it is too difficult to start or manage one. To begin with, there needs to be strong public support to justify deferring resource revenue for future consumption. Even with the support, it is a daunting task to set up an entirely new investment management institution. However, if Alberta, Quebec, and British Columbia already have created a consolidated fund, it is much easier for other provinces and territories to simply join. Having more provinces and territories join the consolidated fund is good news for existing fund holders as well, because the cost of managing the fund will be diluted. As such, a consolidated SWF will increase the number of participating provinces and decrease the cost of fund management per province.

Overall, Canada needs SWF’s in order to prepare for economic downturns, to achieve intergenerational equity, and to support various initiatives and objectives. However, existing SWF’s in Canada are fragmented amongst the provinces and territories. Consolidating the provincial SWF’s and placing them under one investment institution will allow the consolidated fund to have a clear mandate, transparent and autonomous governance, and the ability to attract other provinces to join it. The political process of achieving such consolidation will prove to be very challenging. To realize this goal, Ontario must create its own SWF and become an adamant supporter of the consolidation for two reasons. First, Ontario takes such a large part of Canada’s economy that the consolidated fund will be incomplete without it. Second, the fund should be headquartered in Toronto, the financial hub of Canada, where the fund can recruit the best talent and enjoy spillover knowledge from surrounding financial institutions; a strong support from Ontario is crucial to locate the consolidated fund in Toronto. Nonetheless, even if the consolidated fund is not created within the next few decades, provinces should certainly devise their own. As Norway shows, there is too much benefit in having a sizable SWF for provinces to let that opportunity disappear. With any luck, BC will have a successful SWF; once the benefits are demonstrated, other provinces will jump on the gravy train too.

Featured image from Flickr Creative Commons

Norway’s SWF chart from Qz.com

BC LNG picture from Commonsensecanadian.ca

Caisse picture from Radio-Canada.ca

Citations

[1] http://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings/

[2] http://www.scribd.com/doc/182399660/MacKinnon-A-Saskatchewan-Futures-Fund-pdf

[3] http://www.corporateknights.com/article/rainy-days-leave-alberta-wet?page=show

[5] http://www2.news.gov.bc.ca/news_releases_2009-2013/2013PREM0018-000231.htm

[6] http://www.canadianbusiness.com/economy/learn-from-albertas-mistake/

[10] http://www.thenational.ae/world/middle-east/norway-blacklists-israeli-firms-linked-to-settlements