Out With the Old, In With the Old? Quebec’s 2018 Elections, Eight Months Out

Source: OZInOH via Flickr (http://bit.ly/2nGOWtl)

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

Source: OZInOH via Flickr (http://bit.ly/2nGOWtl)

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/

With a contentious and heated provincial election set to take place only a few months from now in Ontario and a series of crucial midterm contests scheduled for November down south, it is easy to forget that Quebecers themselves will head to the polls by no later than October 1st. By the time voters cast their ballots, it will have been four and a half years since the Liberals came to power in a major upset of the Parti Québécois (PQ), who were widely expected to upgrade their minority to a majority. Instead, the first-ever female Premier in Quebec’s history, Pauline Marois, retired after having been defeated in her own riding. By the evening’s end, a former Liberal Cabinet Minister and neurosurgeon by the name of Philippe Couillard had ridden a red wave straight to the Premiership. In this article, a brief recap of the Liberal tenure vis-à-vis the 2018 elections will be offered, followed then by an examination of each of the other three major parties’ priorities and strategies, concluding lastly with an informed projection of October’s result.

It is undoubtable that the Liberals will enter the 2018 campaign with quite a bit of economic momentum supporting their aspirations for re-election. An unemployment rate at its lowest levels in over forty years, a strong provincial credit rating and steady economic growth are all reasons for optimism. One must not forget the measures that were taken to achieve these outcomes, however. In the early years of its tenure, the Couillard government implemented harsh austerity measures all across the public sector, many of which were met with widespread protests. The extent to which the memory of these policies will weigh on the electorate remains to be seen. On infrastructure, the Liberals most notably wrote a large cheque for the new light-rail project set to begin servicing Montreal’s suburbs in a few years, a major development which could well sustain the Liberals’ stronghold in Quebec’s most populous city.

Like almost any majority government, the Couillard regime has not governed scandal-free. Couillard’s cabinets have been no source of political stability with respect to image: his Education Minister resigned in 2015 over a media uproar regarding a school strip-searching a 15-year old girl, and Health Minister Gaétan Barrette has maintained an extremely fractious relationship with the management of the province’s new super-hospital amid a variety of disappointing developments. While seemingly minor compared to the state of the economy, the “bonjour-hi” debacle – in which Couillard supported a non-binding PQ motion seeking to remove the “hi” portion of the standard greeting – will also not help Couillard’s cause, particularly his standing with Quebec’s anglophone minority, who are often taken as a given in Liberal strategizing. Perhaps the most significant recent controversy incurred by the Liberals has come in the aftermath of Bill 62, a bill that has sought to ban citizens from wearing face coverings when giving or receiving public services, including public transportation, in the name of religious neutrality. Despite being stayed by the courts, the bill was an absolute disaster for the Liberals, garnering criticism from the right as too narrow, and from the left as clearly discriminatory towards Muslim women wearing the niqab.

The past four years have not been so kind to the Liberals’ once-principal opponents, the centre-left Parti Québécois. After curiously selecting the firebrand media magnate Pierre-Karl Péladeau as its new leader in early 2015, the PQ seemed confident in its ability to energize the party base around a household name. This bold move backfired, though, as Péladeau resigned within a year, citing family difficulties. The party was forced to enter into a second consecutive leadership election, with the steadier Jean-François Lisée ultimately securing the victory. In 2017, however, an ever-controversial former PQ MNA by the name of Bernard Drainville insinuated that the PQ caucus was on the verge of replacing Lisée through yet another leadership election. Though quickly brushed off by the party leader, Drainville’s comments have seemed only to confirm the public perception of the PQ as a party divided. In the realm of sovereignty, for which the PQ is notorious, Lisée has taken the moderate position of promising not to hold a referendum on Quebec sovereignty in his first term should he be elected Premier. On the matter of Bill 62, however, the PQ has taken a firmly nationalist stance, outlining their own alternative legislation that would extend the face-covering ban to public spaces.

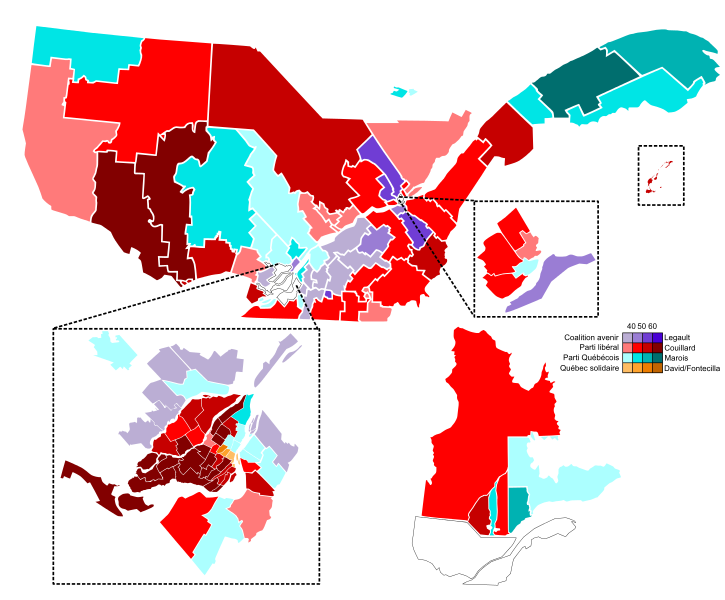

The current favourite to form government later this year is the upstart Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ), led by François Legault. The CAQ enjoys the advantage of having a generally similar economic orientation to the governing Liberals, without the baggage that accumulates over four years in majority government. There does remain a lingering perception of the CAQ as a political “training ground” for the Liberals: Health Minister Barrette, as well as the Minister for Economic Development Dominique Anglade, both ran under the CAQ banner in the 2012 elections. The CAQ must find a way to dispel with this notion should they wish to be taken seriously later this year. Economic campaigning by the CAQ has taken on a more regional character, with a particular focus on areas traditionally considered Liberal or PQ strongholds. While a sovereigntist in his earlier years in politics, Legault has backed off of this stance during his tenure at the head of the CAQ, and now seems firmly opposed to the idea of another referendum. This could play to his benefit among federalist Québécois voters, but he may not be able to flip the anglophone vote in light of his proposal to abolish school boards, seen as a key form of minority representation. On social issues, Legault has seemed to fall somewhere in between the Liberals and PQ. He has criticized Liberal immigration targets as too lofty, advocated for cultural values tests for new arrivals, and echoed PQ complaints that Bill 62 did not go far enough, albeit less vocally. These views, while common among Québécois parties, are either absent from or more moderate within the final major political player in this year’s election: Québéc solidaire.

Currently in possession of only three seats in the National Assembly, the left-wing Québec solidaire (QS) has notably taken the softest stance on Bill 62 of all four principal parties. Co-spokesperson Gabriel Nadeau-Dubois, who first rose to political prominence as a student leader in the 2012 student protests against tuition hikes, believes the bill goes too far but that some face-covering bans are warranted, mainly in the provision of public services and in the case of identification. This past fall, QS undertook a mini-sovereignty campaign oriented towards students. They have also made their appeals to the anglophone left, who were near-equally complicit in electing NDP MPs in the 2011 federal Orange Wave as were their francophone counterparts but have not shown much willingness to support the QS quite yet.

Were the election held today, there is little doubt that the CAQ would capture a majority government, if polls are any indicator. With that said, there are still eight months until election day, and this leaves plenty of time for the Liberal political machine to kick into gear. Though the CAQ are less burdened by controversy than the Liberals, they are also less experienced, having been founded in 2011 and never having formed the government. If the Liberals can trumpet the strong economy they have bolstered while managing to avoid being picked apart on two sides on social issues, another victory may yet be added to their long and storied electoral history. If the Liberals somehow manage to alienate their long-time support among anglophones, the CAQ will undoubtedly benefit.

The prospects of the PQ seem quite grim at the moment, but if the party can overcome its internal disunity and develop a clear platform under Jean-François Lisée, they are not to be counted out. Crucially, the PQ will need to appeal to the centre on some level without compromising the leftward elements of their base, as it is evident that public attitudes in the economic realm seem to favour the rightward Liberals and CAQ. Lastly, Québec solidaire could seek to capture a few more seats on the island of Montreal through their progressive stances on social issues, which seem to mirror those of a city whose former and current mayors have roundly criticized Bill 62.

Just less than eight months away from the projected election day, only one thing is for certain about Quebec’s 2018 election, and that is that nothing is for certain.

This article has been edited by: Thea Koper