The Journalist’s Dilemma: Game Theorizing Terror Journalism (Part 2 of 2)

This article is the continuation of a two part collaborative series on the journalism of terror. Part One by Margot Charles was published last week.

As outlined in Part One of this series, the broadcasting of terror videos and photographs fulfills the aims of terrorist groups to send their messages to the public. The decision of whether or not to broadcast between different networks can be modelled using the Prisoner’s Dilemma model of Game Theory. However, traditional media sources such as TV and newspapers are no longer the only sources of information in our technological world. Twitter, personal opinion blogs, and YouTube, all controlled by private individuals, have also become providers of news media. The Prisoner’s Dilemma can also be applied to these less traditional forms of information dissemination, which for the purpose of this article will be categorized as internet-based citizen journalism. For the purposes of the model, all traditional media sources and all internet-based citizen journalism will be grouped into their own, unified category, in order to model the Dilemma as a two-by-two table. The decision of whether or not to broadcast a terror video, such as the recent, highly publicized, ISIL beheadings of American journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff, can be modelled as shown below:

|

Traditional Media Internet Citizen Journalists |

Releases | Doesn’t Release |

| Releases | Outcome A | Outcome B1 |

| Doesn’t Release | Outcome B2 | Outcome C |

Outcome A: Both traditional media networks and internet-based citizen journalists release the video, the terrorists get what they want as their message gets spread out.

Outcome B1: Traditional media networks don’t release the video, their network is hurt by the loss of audience caused by the shift to internet sources of citizen journalism since they released the video. The terrorists get what they want although to a lesser-than-optimal extent since their message is likely to reach a smaller audience.

Outcome B2: Internet-based citizen journalists don’t release the video, their sites are hurt by the loss of audience caused by the shift to traditional media networks since they released the video. The terrorists get what they want although to a lesser-than-optimal extent since their message is likely to reach a smaller audience.

Outcome C: Neither the traditional media networks nor the internet-based citizen journalists release the video. The terrorists do not get what they want, and their message doesn’t reach a significant audience.

Assuming that both traditional media networks and internet-based citizen journalists are rational actors, they are motivated in this decision by two competing desires – the desire to boost their source’s popularity and profitability and the desire to conform to norms of respect for the dead and not aiding terrorist goals. For each category, the ranked list of outcome preferences is as follows:

Internet Citizen Journalists: Outcome B1 > Outcome C > Outcome A > Outcome B2

Traditional Media Networks: Outcome B2 > Outcome C > Outcome A > Outcome B1

So far, the stable equilibrium has been in Outcome A, which provides the terrorist group’s ideal outcome. As in other examples of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, the issue is one of collective action: lack of communication between the types of media sources means that there exists no credible assurance that the other will not broadcast the video, and thus prompting both parties to release it. This would suggest the creation of an open forum for discussion between media sources in order to share their intent and increase possibility for credible assurance that no parties involved will broadcast a terror video. Furthermore, states could enact legislation to punish media sources which publish terror videos in order to deter from the incentive to defect from such an agreement.

However, as one can see in the simplified version of reality the model provides, things really are not that easy to fix. First off, the Prisoner’s Dilemma and the ensuing issue of collective action is not limited to two unitary actors: within both categories there exists a multitude of independent actors. This is especially true for internet-based citizen journalism, where not only an unlimited number of actors can exist, but there can also be a quasi-uncontrollable crossover of terror information and footage between nations. Therefore, it is realistically impossible to envision a voluntary system of credible assurance that a terror video will not be broadcast on either traditional media networks or Internet sources of citizen journalism. What remains then, is for a legal mechanism to assure that no sources of any type will publish the terror video.

But here we infringe on the treasured freedom of the press, freedom of speech, and arguably, net neutrality. A government passing laws on the types of content permissible on TV as well as on YouTube, even for motivations of fighting terrorism and national security, lends itself to unfavourable comparisons to dictatorships or dystopias à la 1984. In democratic societies where the question of the Journalist’s Dilemma is most applicable, this would be highly unlikely to be supported by the population, and therefore is not a realistic solution to the issue at hand.

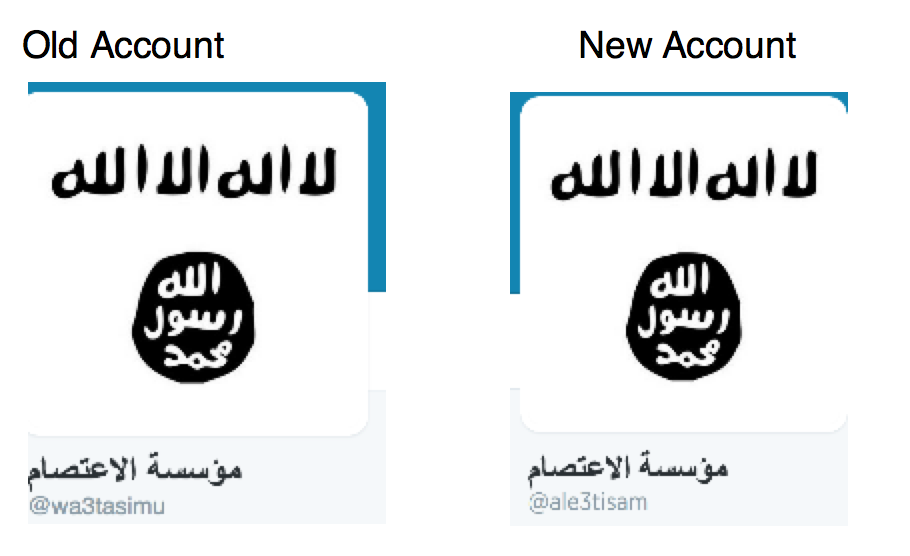

In addition to the popular unfeasibility of government legislation against the broadcasting of terror videos, it is also likely to be ineffective. This is because besides the multitude of actors in both the traditional media and Internet citizen journalism sources, there is a third group of actors not included in the model. Terrorist groups, as well as their unaffiliated supporters, also have access to diffusion sources for their terror videos, which they obviously use to the greatest extent possible in order to disseminate their videos and the messages of fear and total commitment to their cause. One of IS’s most notable achievements is their effective use of social media platforms to publish their home-made terror videos of battles and beheadings and to recruit young jihadists from across the globe. Twitter is an example of the cyber-battlefield which social media has become in these cases: the social media giant struggles to identify and shut down IS’s many accounts, only to have them pop up again under a different name a few days later. While this game of cat-and-mouse has probably somewhat impeded IS’s social media growth by making it a chore for the group’s followers to track down the new accounts every few days, it has not prevented it from amassing significant amounts of followers all the same. IS is also moving to other networks, such as Diaspora, which are even harder to monitor, in order to spread their content. Both governments and the social media and Internet companies are aware of this issue; October saw a meeting between the EU and representatives of Google, Facebook, and Twitter to discuss possible solutions. However, nothing concrete has come of it thus far, leaving us faced with the quasi-impossibility of controlling the dissemination of terror videos.

Besides the near impossibility of stopping the broadcast of these gruesome beheading videos, we must also wonder whether it is actually desirable. Yes, releasing them to the public does play into the terrorists’ hands, but is restricting the information our public gets worth it? An informed public is key to democracy, and with the debate over how to respond to IS expansion and mass atrocities, it is crucial that the populations be presented with all the facts of the group’s actions. Rather than censoring these videos or the accounts of beheadings and other atrocities, the focus should be on the context and narrative the information is framed in. Efforts at reducing the sensationalism which often surrounds broadcasting of terror videos should be encouraged, so that media consumers are presented with the facts rather than the exaggerated and hysterical tabloid-like accounts meant to sell increased copies, allowing them to have more rational ideas to communicate to their elected representatives. However, how do we enforce such a rational approach when sensationalist narratives characterize the majority of today’s media? We are left with the same head-scratcher of collective action. The conclusions are rather bleak: all we can really hope for is that a Constructivist style norm of objective media coverage will rise in our much-loved free press and that Internet users will discover their conscience and a taste for rationality they hitherto ignored. Or, we can watch the myriad videos of cute furry animals which make up the other part of the media after being sufficiently scared by the gory fates of IS’s enemies.