Post-Zuma Challenges: What’s Next?

“The biggest mistake we ever made in the ANC was to make Zuma president.”

Overtaken by corruption affairs and pushed towards the exit by his party, the African National Congress (ANC), Jacob Zuma decided to resign on February 15th from the Presidency of the Republic of South Africa. He leaves behind him mixed feelings.

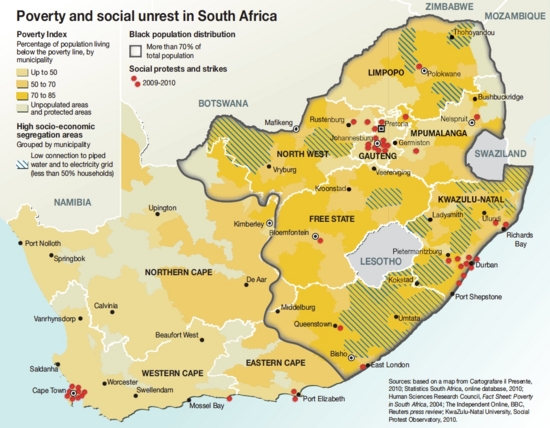

The former president’s attempts to foster democratic values and economic development were often discredited by his personal characteristics. Part of his key measures to improve South Africans’ living conditions was his 2010 overhaul of South Africa’s HIV/AIDS policy, rolling out life-saving antiretroviral drugs. However, his government faced criticism for poor economic performance, growing unemployment, poor service delivery and corruption. His own financial prosperity is especially difficult to accept for the population, because of the rising poverty in the country. More than half of the South African population was under the poverty line in 2015. Zuma had several opportunities to abuse his power, giving him less legitimacy. In his second term, Zuma faced one of his biggest scandals, the $23 million refurbishment of his private residence with the constituency’s tax money. Zuma refused the opposition parties’ demands to pay back the money. This political uncertainty and decline of confidence towards politicians led the International Monetary Fund to lower their expectations for South African economic growth for the next two years.

Due to Zuma’s corruption trials’ aftermath, the majority of the ANC National Executive Committee’s (NEC) members agreed on February 12th to withdraw him from power. Zuma was replaced by Cyril Ramaphosa, the Vice-President of South Africa and ANC President. In the early 1990s, Ramaphosa was an ally of President Mandela during his talks to end apartheid. Some members of the NEC testified that “The biggest mistake we ever made in the ANC was to make Zuma president” and that he was a barrier for the party’s future. This tense climate will be a challenge for the new president, as he will have to work to unite his divided party. In fact, with the upcoming 2019 elections, the goal of the ANC is to reinforce its legitimacy in the South African political scenery. Ramaphosa will have to improve the party’s image after years of allegations of corruption. This division within the party has been translated into a decline of confidence from their voters at a local scale. During the 2016 local government elections, national support for the ANC fell to 56%. Many hope the party of Nelson Mandela will be able to reverse this trend under the leadership of Ramaphosa.

The newly elected President should take away from the Zuma years that the scourge of corruption is an emergency and a hindrance for the country’s democratic transition. He will have to face many challenges, including the reconstruction of the population’s trust towards the politicians and to restore the image of stability given by political institutions. Mandela’s ally will also have to reform the economy, with unemployment is at 30% and youth unemployment at 40%, and redress the drift of recent years.

On Wednesday, February 21st, less than one week after Zuma’s resignation, Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba introduced the outline of his 2018 budget, describing it as “tough, but hopeful”. Ramaphosa’s government has chosen to go forward with strict austerity measures to redress the economy. The main one is the increase, for the first time since 1993, of the Value-Added Tax (VAT) from 14 to 15%. This budgetary trend is strongly denounced by unions because of the potential negative impacts on the poorest households. The increase of the VAT, which should bring to the government approximately 36 billion rand overall, should be used to increase the competitiveness of the country by financing free higher education for the modest income population.

Education is seen by the new government as a tool to break the cycle of poverty. By allowing the whole population to have access to the right of education, the South African government wants to follow the post-apartheid policies narrowing the socioeconomic legacies of apartheid. They want to give the ability to South Africans to have access to decent living standards and economic opportunities by entering on the job market. This policy of developing living conditions would also allow the government to obtain better results in terms of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). An increase in GDP, calculated on the basis of the value of goods and services produced by the population, would allow South Africa to have a bigger impact on the international level. However, even if this budgetary trend aims to reduce social inequalities between South Africans, NGOs such as Black Sash strongly denounced the negative impacts of this measure on the poorest households such as an increase in child starvation. The government has promoted to counterbalance these arguments their project to increase access to social grants. Although, in a country where extreme poverty is already hitting the population, the majority of the South African people already have debts, due to previous loans to have access to basic facilities such as food. These social grants proposed to balance the increase of the VAT would worsen the poorest’s living conditions by increasing their debts.

To boost South Africa’s economy, Ramaphosa will have to act quickly by taking measures which will end the era of path dependency, where developing economies are reliant on natural resources and geared towards exports. To reduce their debts, countries of the Third World take advantage of globalization by relying on the sales of their resources and utilities to multinational corporations, such as in the case of South African water privatization. Selling water rights as a concession to international corporations allowed the government to obtain revenue from that. The implementation of these companies is frequently synonymous with a violent coercion of labour. Such privatizations often expand the inequalities between the high-income population and low-income population, creating disproportionate impacts on poor such as water-related diseases. Poorer populations could not absorb the move from getting free water to having to pay. In the future, the African BRICS member will have to find more efficient solutions to pay their loans back to the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) without harming the poorest population.

Thomas Papernot is currently pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in International Development Studies and Political Science at McGill University.