Who Does Alexander the Great Belong To? | Part 1

https://flic.kr/p/oceVGJ

https://flic.kr/p/oceVGJ

Editor’s Note: This article is the first of a two-part series on the naming dispute between the “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” and the “Hellenic Republic” In Part II, Archimandriti interviews two figures who share their varied perspectives on the debate.

On March 3rd more than 100 people rallied around the Washington Monument in D.C. to assert their right to be called “Macedonians”. Donning vibrant yellow and red colours to represent their nationality, they danced to their customary music, rejoicing in their culture.

Just eight days later, the Canadian Hellenic Congress held a similar rally across the street from McGill University outside of the Greek Consulate in Montreal. Their rally, however, was for a different reason. Greek people from all over the island of Montreal, dressed in their traditional white and blue, banners and flags in hand, gathered to protest the name of the country to Greece’s north.

The right to the name “Macedonia” has been the subject of an acutely sensitive dispute between Greece and its northern neighbour since the end of the Socialist Federal Republic of Macedonia in 1991. In 1993, the UN provisionally approved the naming of the newly independent state — brokered out of the collapse of Yugoslavia — as the “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” (FYROM). After much deliberation, and to the dismay of local Greeks, in 1995 the Hellenic government and its Balkan neighbour signed the Interim Accord, in which Greece agreed to recognize the new state as the “FYROM”.

Since then, most countries across the globe — including four permanent members of the UN Security Council — have refrained from using the FYROM’s provisional reference; to the displeasure of Greece, many recognize its neighbour as the “Republic of Macedonia“. To this day, the two states continue to debate Macedonian nomenclature, and the quarrel has provoked barriers for the entry of the northern country into the EU and NATO. But why exactly does Greece oppose the “Republic of Macedonia’s” name? What are the historical and contemporary arguments that each side use?

For the purpose of clarity, this article will utilize the provisional description of the FYROM as it is referred to internationally. Nonetheless, this does not imply that the article will take the side of either nation.

A History of the Macedonian Region

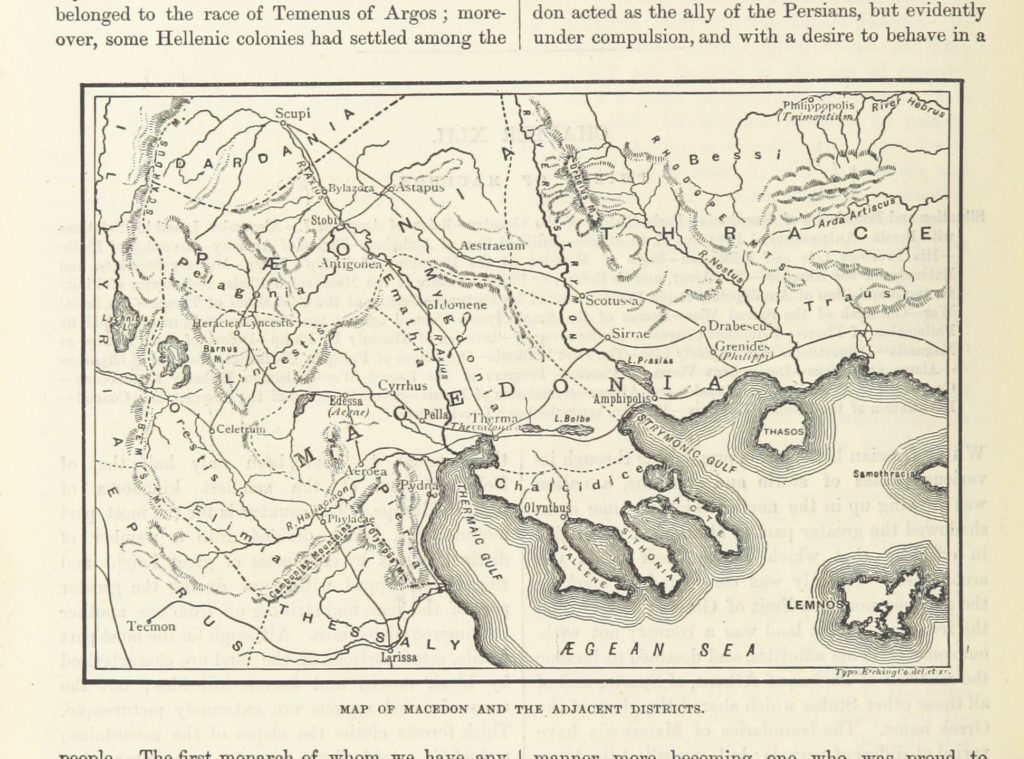

The general region of Macedonia can be geographically defined as the area containing present-day Northern Greece, South-Western Bulgaria, FYROM, and small parts of Albania, Serbia, and Kosovo. Historically, this part of the Balkan peninsula has been inhabited by various peoples. The earliest Indo-European people settled in the region during the early Bronze age, forming the Paeonian tribes. Later, Philip II of Macedon, a Hellenic king, conquered a weakened Paeonian state and named it Macedonian Paeonia. His son Alexander the Great would continue his legacy, annexing the remaining territory of the modern-day region of Macedonia and consolidating it under one state, for the first time. When the Romans conquered Macedonia around 146BCE, this area became a Roman province that included Northern and Central Greece, small parts of present-day Albania, and most of contemporary FYROM. Its capital was Thessaloniki, a present-day Greek city.While situated on the border of Macedonia and Dalmatia, Skopje (Scupi during Roman times), the modern-day capital of the FYROM, was a part of Dalmatia.

After the division of the Roman Empire in 293CE, the region of Macedonia was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire. When the Byzantine Empire collapsed in 1453, Macedonia switched hands yet again, this time as a part of the Ottoman Empire. Centuries later, much like the Greeks during the Greek War of Independence in 1821, many different groups in the Balkan peninsula fought against their Eastern conquerors. With the decline of the Ottoman Empire and the ensuing Balkan Wars in 1912-1913, the region of Macedonia was divided between Greece, Bulgaria, and Serbia — with FYROM under Serbia. After World War I, Serbia (with the region of present-day FYROM in tow), merged with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes to form what was known as the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

After the end of WWII, the “People’s Republic of Macedonia“, a state formed during the National Liberation War of Macedonia in 1944, was formally incorporated into the People’s Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. During this time period Yugoslavia, under President Tito, followed other Eastern European countries into communism. Greece fell into civil war shortly thereafter, with its communists, supported not only by the USSR but by the Socialist Republic of Macedonia as well, combating the UK and USA-backed Greek Government army. By 1991, the USSR and the various countries under its communist umbrella collapsed, and thus, the then Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia declared its independence from Yugoslavia on September 1991. It was the only country to break from Yugoslavia peacefully.

The FYROM nowadays is thus comprised of a mixture of different peoples, namely more than 60% ethnic Macedonians, a quarter Albanians, and up to 6% Turks and Serbs. Their language thus also consists of a blend of Bulgarian and Albanian.

Modern Tensions — Alexander the Great, Greek or Macedonian?

Since the breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991, the newly independent Socialist Republic of Macedonia (which would later be recognized internationally as the FYROM) has argued with the Hellenic Republic over its name. Today, Macedonia is the name of not only the modern Balkan country but also of three northern provinces of Greece. The 240,000 inhabitants of these provinces also identify as Macedonians, creating yet more confusion and friction between the two nations.

As already implied, both of these areas were part of the greater Macedonian region which Alexander the Great unified long ago. Historically, this ancient Macedon Kingdom was centred on the northeastern part of the Greek Peninsula. Geographically, present-day Macedonia equates to the aforementioned Paeonian land. Nevertheless, the ambiguous nature of the region’s name has heightened tensions over who “deserves” the name Macedonia, and as well as the history associated with it.

Greece’s frustration first came to light in the early ’90s, when its government, as a means of isolating its new neighbour from the European Community, urged for a declaration which would guarantee that neither country would make “territorial claims towards a neighboring Community state, hostile propaganda and the use of a denomination that implies territorial claims”. This, nonetheless, failed to pacify Greek fears. Mass rallies took place in 1992 across Greece and its diaspora communities, similar to the recent rallies. Greeks gathered to protest the mere existence of any reference to “Macedonia” in its neighbour’s name.

However, the Greek community was not the only dissatisfied party. Its northern neighbours, who had recently secured their independence from Yugoslavia, refused “to be associated in any way with the present connotation of the term ‘Yugoslavia’,” nervous that the reference would urge Serbia to make territorial claims against them as well. Ultimately, both sides disagreed with the reference the UN adopted for the FYROM, and while it was accepted by the lenient governments of the countries at the time, it was and still remains heavily contested by opposition leaders and citizens of Greece and the FYROM. Both governments were seen as weak for succumbing to the will of the UN by failing to follow their own national interests.

The name of the country to the north of Greece was not the only source of dispute. The flag that the FYROM had proposed in the early 90s included the Vergina Sun, a symbol that can be traced back to the ancient kingdom of Macedonia. Since the 1980s, the Greek region of Macedonia formalized this yellow eight-spiked sun as its flag; a symbol historically found in the city of Vergina, Greece. This connection between the ancient kingdom and Greece serves as one of their claims to “Macedonia” and its associated history. The choice of their neighbours to adopt this symbol enraged the Greek population, leading to Greece imposing an economic blockade on the FYROM and blocking the UN from flying the flag in any location of importance. Greece also used the Interim Accord to attempt to block their neighbours from using Vergina sun “in all its forms“. Eventually, FYROM decided to appease their southern neighbours and changed their flag to the new eight-rayed sun.

To this day the naming dispute remains unresolved. Despite heavy nationalist spirits in their populations, the two nation’s prime ministers, Alexis Tsipras for Greece, and Zoran Zaev in the FYROM seem to be working together to reach a compromise. Zaev has taken various measures such as renaming the largest airport of his country from “Александар Велики“ (“Alexander the Great”) to “International Airport of Skopje”, as well as renaming the country’s main highway to “Пријателство” (“Friendship”). Zaev hopes to display that his nation is not appropriating the culture Greece is so proud of, slowly putting out the fires of the complicated diplomatic and cultural dispute. On the other side, Tsipras, despite disputes with the Greek parliament, seems to accept a composite geographical name for the northern country that could contain the name “Macedonia”.

Edited by Alec Regino