A Decades-Old Storm: Professor Carolina G. Hernandez on the South China Sea

https://flic.kr/p/XojrRf

https://flic.kr/p/XojrRf

With slowly intensifying conflicts brewing in the South China Sea, neighboring governments are constantly finding ways to defuse tensions not only between other countries, but also to calm the anxieties of their citizens. China continues to enforce its will on the region, a show of strength that has not changed over the years. What has changed, however, are the governing administrations of China and the South East Asian countries and their approaches to the issue. Due to this, resolutions seem to be reliant on the judgments of the current government. In truth, the challenges in the South China Sea span decades of negotiations, administration shifts, and issue re-framing.

I sat down with the University of the Philippines’ Professor Emeritus (Political Science), Carolina G. Hernandez, to get more insight on the issue; in particular, the importance of labels, the roots of the problem, and possible militarization. Not only has she had decades of research and lectures to share with students, but she has also been part of numerous conventions, conferences, and organizations dedicated to creating sustainable solutions to the issues that come with sharing a sea. Currently, she is the founding President of the Institute for Strategic and Development Studies Inc., on the board of editors for Cross Border Cooperation and Human Security in East Asia, a supervising member of the governing board of the Human Rights Resource Centre (HRRC), and a member of the advisory group of the Oxford Research Group on Sustainable Security. From the 1980s to today, professor Hernandez has been actively participating, advising, and contributing to boards and conferences on issues of the South China Sea: co-chair for the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP Philippines), ASEAN co-chair of the steering committee for the regional CSAP, and chair of the United Nations Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Disarmament Matters (ABDM), just to name a few. Clearly, she is the best choice to advise on current issues experienced in the disputed sea.

HM: Do you think that this [the nine-dash line[1] versus United Nations border definitions[2] ] is a source of contention that should be debated over? Should we just follow the international conventions?

CH: It’s easy to [say] that international conventions should be obeyed, but we know that conventions are probably less important than the paper, the ink on which they signed their names… So for me, the important thing is how countries and their peoples particularly interfaced with the features in the South China Sea.”

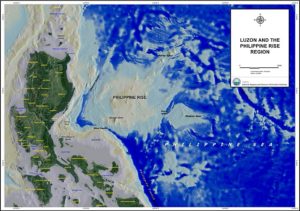

HM: So speaking of labels, do you think the labeling matters? There’s a focus here in the Philippines of naming the South China Sea, which is known to everybody (in the Philippines) as the West Philippine Sea, or the Benham Rise[3] as the Philippine Rise. Do you think this is important sort of propaganda or does it really matter to you?

CH: For me it doesn’t really matter because I believe that a rose by any other name is still a rose, so for some people names are important, but not for me. That’s why when you talk about the Benham Rise, Benham was an admiral of the United States I think. So now, it’s Philippine Rise, but it’s actually even less Filipino; it’s foreign. So there is nothing indigenous about the “Philippine Rise”.

HM: So why do you think then that this administration really wants to relate or relabel these things [as “Filipino”] as they present them to their people?

CH: I think there’s a tendency to respond to the majority population of leaders. During the previous administration, under the Liberal Party of Mr. Aquino, we labeled the South China Sea as the West Philippine sea… the reason for this is because you yield to the Chinese… So it’s only an international labeling I think. But during that time of Mr. Aquino, we called it the West Philippine Sea, and there’s a distinction between the South China Sea in the West Philippine Sea. The West Philippine Sea belongs to us. It’s not part of the contested area, according to the previous administration. And I think that Mr. Duterte, in renaming the Benham Rise to Philippine Rise is probably also doing the same thing. But for me it doesn’t really matter.

HM: So in terms of the use of islands, do you think it’s a rising concern because there could be [possible] militarization but it’s not from the Philippines?

CH: I think personally that the so-called militarization of the South China Sea slash West Philippines (laughter) should not bother us too much because the South China Sea had been “militarized” before. The first time that the Chinese, for example, claimed an island belong[ed] to them was in 1995 I think during the so-called Mischief Reef incident. And the president of the country during that time was Mr. Ramos, and he agreed to believe in the Chinese’s justification for action, which is that these were fishermen shelters and that they were not authorized by Beijing to build the fishermen shelters because it’s an independent action of the Philippines, the PLA Southern Command of the PLA Navy.

So I have two problems immediately, Bianca[4]. One is what happened to the Arctic control over the army, and number two, now that Beijing knows about the issue, what is Beijing prepared to do? Nobody could answer those questions to my knowledge. So we agreed to allow the Chinese to be there and it’s true that the former president Ramos tried to defend the sovereignty of the country against the Chinese during that time by destroying buoys that were put up by the Chinese government. But I think you cannot think about what happened now, the so-called militarization, without thinking about the first incident. This was 1995 and in 1998 we discovered that they militarized the Mischief Reef by blasting corals so that the channels will be deeper and that will allow the navy to station there. So that was the first incident and all of these things that are happening now, are extensions of that first move, I think.

HM: Do you think there’s any “right” way to go about this problem or it’s just whatever is most beneficial should be followed?

CH: A lot of people, Bianca, are talking about joint activities, but in 1992, that decade of the nineties, there was a Canadian and Indonesian initiative. The so-called “Informal Working Group on Managing The Conflict in the South China Sea”. “Managing the conflict” because [it] will not resolve the conflict. You can only manage it. And I thought that was smart of the Canadians and the Indonesians at that time. They have already talked about the joint exploration or activities of the sort that we’re talking about right now. So everything is being recycled, but people forget about those early days.”

HM: So with that, [the] international community’s response is obviously very important. Do you think the response of the international community is going to be important for this or China and the Philippines should just ignore and talk about joint activities?

CH: The problem, as I see it, is that the international community tries to meddle in all these issues that really do not concern them directly as much as they concern the Philippines, for example, on the one hand, and China on the other. Here, it is the Philippines that is really at the centre of it all. But you know very well that the Philippines is helpless. In fact, the current president already [said]: “you want me to go to war with China?” But who [is] going to go to war with China at this point? Not even the United States, because I think at the end of the day, everybody’s thinking about the economic benefits that help beef up the important positions of countries such as China on one hand and the United States or the Philippines [on the other].

HM: So because economics is the main issue, you would say no, China will not declare war on the Philippines?

CH: No, I don’t think China will declare war on the Philippines. Especially during this time. In fact, there are issues I cannot talk about. But I can tell you that there are certain things that the Philippines makes China comply with –hard as it may seem to understand or to think about it.

HM: Do you have any predictions on what’s going to happen there?

CH: The problem, as I see it, is that everybody thinks that in the current power shifts that are taking place, China has the upper hand. And you know very well from your study of international relations that whoever is the most powerful in the international system will waive the rules. And China, I think, is doing that. It has learned its lesson very well from past international relations.

HM: You believe that China, as long as they have power, will continue to do what they want?

CH: Yes, I think so.

In her professional opinion, China will simply continue to exert force, physically or economically, in order to get what they want. However, the nuclear option of going to war probably will not happen in the area, for China still needs the other neighbouring countries. Especially with the United States meddling with international affairs, it is vital that China will gain an ally or at least has positive relations with countries in the area. The Philippines will have to make the most of the situation. Duterte will continue to project control over the area, just as his predecessors have; may it be through renaming areas or talking tough in speeches, the president needs to calm domestic anxieties over territorial disputes. The only way to make China listen is through economic discussions, so Manila will have to find clever ways to reap the benefits of resource-rich areas in the sea.

This storm has been brewing for decades, and the Philippines is still far from reaching the clear. As long as China continues to be a more dominant power, Manila will have to learn to ride the waves instead of trying to stop them. For now, the calm is merely just the Philippines reaching the eye of the storm–a conflict far from over.

Footnotes

[1] The nine-dash line was etched into maps by Chinese cartographers in 1947. The area suggests that all within the declared border is China’s territory.

[2] The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was signed to define marine “areas” and aquatic “borders” between countries. Section 2 Article 3 defines borders as, “Every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention.”

[3] The Benham Rise is a resource-rich, underwater plateau to the east of the Philippines. It is one of many contested areas between the Philippines and China.

[4] Bianca is one of the author’s 2 first names

Edited by Alec Regino.