Feudal Ties and Pakistani Elections

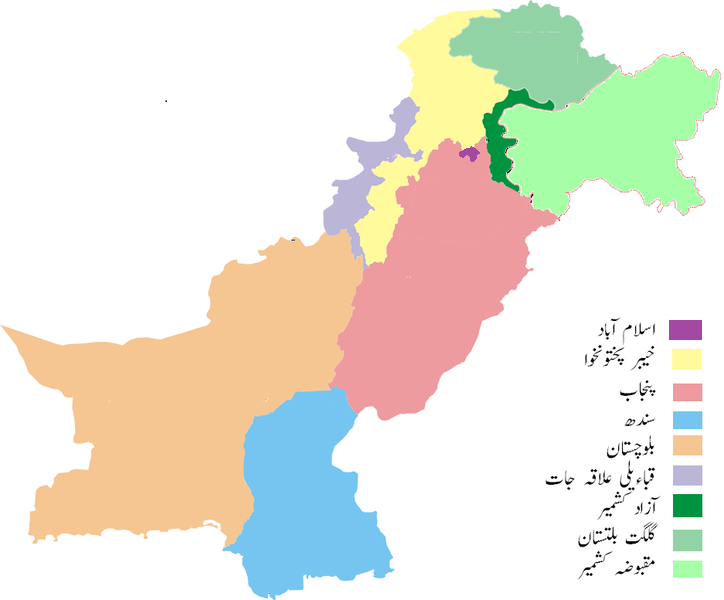

By Shehzad.ali.id [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

By Shehzad.ali.id [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons

Leading up to Pakistan’s 2018 national elections, familiar contentions made their way back into the spotlight. It’s the civilian government’s second democratic transition since the country’s independence in 1947, and pressure is high. The military dramatically increased its presence to monitor the process, there were suspicions of polls being rigged, major media outlets faced a greater intensity of censorship, violent terror attacks tainted the polls, and candidates’ corruption scandals linger. Like many of these setbacks, the power imbalance within society is one that has persisted through the decades but holds an incredible importance for Pakistan’s progression.

This power imbalance includes discrimination against minority ethnic and religious groups, gender inequality, and economic inequality. These can all be tied to the remains of feudalism, a system that plays on tradition and tribal ties, and which dates back to a time before the state’s existence. In fact, feudalism’s inception in Pakistan coincided with British colonialism, as officials granted profound administrative capacity to eminent Muslim landlords. Now, they make up the elite landowning class. Their power transcends economic wealth and feudal landowners also wield immense influence in the political and legal spheres.

The rural population bound under these landlords constitutes not only a crucial part of Pakistan’s agrarian economic sector, but also a large part of the vote, especially in the Sindh and Baloch provinces. As is often the case in developing countries, much of the bubbling activism and progression in the country is occurring in the urban-residing middle class, while the rural lower-class is trapped in cyclical poverty. Because of this, there is the external force of obligation to land proprietors that perpetuates their lack of access to education, employment, health and financial resources.

Over the years, the hundred or so families that are known as prominent feudal lords have kept leaders that support their status and power in office. This leaves a staggering inequality in place. Although both recent land and electoral reforms have partially diminished their holdings, the social imbalance which enables them to sway their workers’ behaviour prevails. Some have even opened their own jails, as the ability to administer justice permits them to do so. By exploiting the economic disadvantages of the lower class, they promise (or coerce) material benefit in exchange for votes and compliance. Not to mention, beneficiaries of feudalism often align themselves with the military, and become political candidates themselves. One of the most popular examples is the Bhutto family from Sindh. Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, who inherited the Pakistan Peoples’ Party (PPP) from his mother Benazir Bhutto, was one of the three main candidates in the election. The ubiquity and hierarchal status of these leaders makes it nearly impossible for villagers to stand up and vote for a candidate who might actualize change in their favour.

Feudalism in Pakistan is a much-discussed issue, but one which loses its gravity amidst the chaos of corruption scandals and militant activity. However, changes to feudalism are conducive to reforms in corruption and security. The end of feudalism in Pakistan could effectuate true suffrage for thousands of previously manipulated citizens and enable them to vote for worthy candidates. First and foremost, it would be a tremendous step forward for democracy and truly free and fair elections in Pakistan. Relieving the economic and political strain on the rural population while lessening the stronghold of the landowning elites would also slowly work to close inequalities.

But what exactly does the end of feudalism in Pakistan look like? Essentially, it should be gradual land redistribution in order to increase the tax-base. According to World Bank data, tax revenue as a percentage of GDP for the country is one of the lowest in the world. Legal reforms are needed in order to promote economic empowerment for rural tenants. The reason they haven’t already been efficiently implemented is the corruption of incumbent officials, voted in by the elite. Although after the recent elections, more and more people are ready and willing to speak out for change. Especially amidst the modernizing force of social media, voters have a new scale of awareness; after journalist Gul Bukhari was abducted for criticising the military, outcry from activists and supporters on Twitter led to her quick release.

Incoming Prime Minister Imran Khan of the Tehreek-e-Insaaf party (PTI or “Pakistan Movement for Justice”) promotes an ideology of developing a welfare state rid of corruption, military bureaucrats, and feudal leaders. However, in order to acquire enough seats to have a majority, the PTI has to band with “large rural landholders known as “electables” . Their support is essential, but many also tend to oppose measures like modernizing the country’s labor and tax laws. The PTI won 109 of 269 seats at the National Assembly. Khan will have to choose his allies carefully. He must discontinue support for elite landowners in politics, while maintaining the party’s power against the rival Pakistan Muslim League, Nawaz Sharif (PLM-N). Of course, he will also face bitterness from the military leaders that receive large shares of land for their service, which are often rented out to feudal lords. It is a complicated, ambitious, but necessary step for enabling swift reforms and recovering the economy from years of mismanagement. Khan will have to stick to his victory speech, and “run Pakistan like it has never been run before”.

Edited by Gracie Webb