Spot Fixing the Pakistani Election

Twenty six years ago, Imran Khan captained Pakistan to its first ever World Cup championship after narrowly beating England 249/6 to 227/10, having scored a decisive 72 runs and taking the last wicket of the game. Since then, Khan immortalized himself as not only a cricketing legend, but also as a beacon of hope for the country. To many, he brought more pride and happiness to the nation than any other dynastic statesman or military general before him. The media branded him a national hero; political parties clamored to gain his favor; and millions across the country chanted his name. Thanks to Khan & co, Pakistan celebrated its greatest day since Independence.

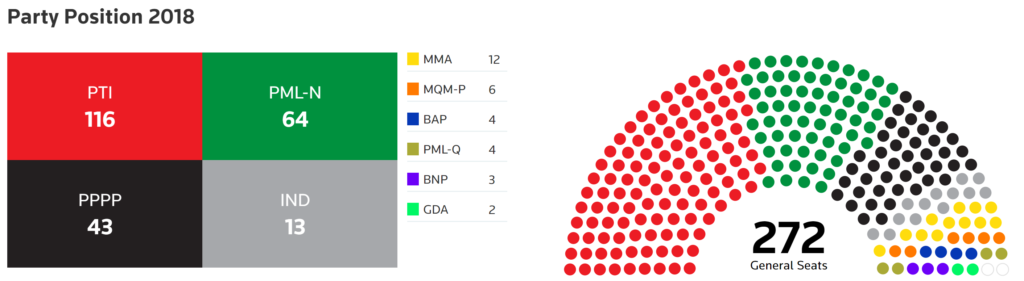

Today, these jubilant scenes were seen once again when Khan’s ‘Pakistan Tereek-e-Insaf’ (PTI) party was triumphant in the 2018 Pakistan general election. However, this time, the victory wasn’t as clear cut. Politicians and journalists across the country claimed that the election was once again rigged by the military. Khan categorically denied these accusations, which is ironic considering he would have probably agreed with them had he not won. In 2007, he boycotted the 2008 general election after tearing up his nomination form in protest of President-General Musharraf’s eligibility to stand in the election. In 2013, he lost the general election to Nawaz Sharif’s Pakistan Muslim League (PML) and subsequently launched an anti-corruption campaign against Sharif and the Pakistani deep state, claiming that the military and intelligence services facilitated the PML’s victory via political intimidation, ballot stuffing, and tampered vote counts.

Khan’s campaign eventually succeeded in 2016 – in part thanks to the Panama paper leaks – after it resulted in Sharif and his apparent political heir, Maryam Nawaz, being sentenced to ten years in prison after the two were found guilty of corruption, and misuse of state assets. This eventually paved the way for Khan’s 2018 victory as it not only knocked out his biggest political rival but also helped cement his reputation as an uncorruptable populist. The stars had finally aligned in Khan’s favour, albeit with extraterrestrial support, as the military establishment had also abandoned Sharif as he became a liability thanks to his tug of war with the military over greater civic powers in Pakistan’s governance and foreign policy.

With Nawaz Sharif out of the way, combined with PTI’s recent military backing and pivot to the Islamist right, Khan was virtually unchallenged with no opponent who could realistically compete against him. Shortly before the election, the PML scrambled to promote Nawaz’s lesser known – and even less charismatic – brother, Shehbaz Sharif, as a viable candidate to its pro-military voter banks in Punjab. The Pakistan People’s Party’s tenure in 2008 with Asif Zardari left a bad taste in so many Pakistani’s mouths that the thought of his son Bilawal Bhutto-Zardari – a self-entitled twenty nine year old who has no governance experience and can barely speak Urdu – winning the Prime ministership would have sparked nationwide nausea. The other parties didn’t stand much of a chance either due to their lack of ‘electables’ and focus on ethno-political niches with many made up of pro-Taliban religious zealots (Muttahida Majlis e-Amal), Karachi mobsters (Muttahida Qaumi Movement), and secular Pashtun nationalists (Awami National Party). Moreover, what must also be noted is that this election was one of the most violent in recent decades with over a hundred people killed in suicide attacks. Party officials from PTI, BNP, JUI-F, and ANP were also surgically targeted by terrorist organizations in order to disrupt voter turnout and to get rid of high ranking party officials.

Following Khan’s election win, many of the aforementioned parties have banded together to protest the election results but it remains to be seen if any meaningful investigation will be taken. Sharif wasn’t kicked out of power because of an investigation into foul play in the 2013 elections – which never happened – it was conveniently because of the Panama Papers and his own daughter’s comical attempt at document fraud. Knowing this, the anti-PTI coalition will definitely try to dig up as much dirt on Khan as possible. It wouldn’t surprise me if Khan’s rivals uses his playboy past against him – which consists of a laundry list of ex-lovers and failed marriages – in order to undermine his credibility with his Islamist political backers.

So, was the election rigged? Most probably, yes. This isn’t particularly surprising to me, or anyone following the region, as military intervention is the price Pakistani democracy has historically paid in order to avoid another coup d’etat – even Imran Khan knows this. There’s a reason why not a single government before Asif Zardari in 2013 was able to complete its five year term in office, and its that you either rope yourself to the military, or they tie one around you – just look what happened to Z.A Bhutto in 1979. The statistics aren’t encouraging either as Pakistan is ranked 110th in The Economist’s 2017 Democracy Index and received a score of 32% in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index.

What’s next for Pakistan’s foreign policy?

China

Imran Khan has made no secret of his admiration for China. He mentioned China seven times in his televised speech to the nation after his election win where he extolled the People’s Republic for lifting hundreds of millions of peasants out of dire poverty and even promised to emulate the Chinese Communist Party’s anti-corruption policies. In a symbolic gesture, the Chinese central bank lent $2 billion to the State Bank of Pakistan two days after Imran Khan’s victory speech, leading to a sharp rise in the Pakistani rupee against the US dollar and a rise in the Karachi stock market. Chinese-Pakistani relations were initiated by then Foreign Minister Z.A Bhutto after the Indian-Chinese border war in the 1960s and a pro-Chinese stance can generate instant legitimacy for a Pakistani politician, as well as an invaluable source of economic patronage. China is also heavily investing into Pakistan with its $46 billion dollar CPEC trade initiative, the showpiece project of President Xi Jinping’s ‘Belt and Road’ Initiative. China’s construction of roads and railways from its Xinjiang province to Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea could seriously transform the strategic and geopolitical equation in South Asia. It also boosts Pakistan’s role as a pivotal state in Great Power politics.

The West

As the trade war between the US and China escalates, Washington is suspicious about Islamabad’s financial obligations to China. President Trump has slashed Coalition Support Funds military assistance to Pakistan even before Khan’s election. Secretary of State Pompeo has publicly opposed any IMF bailout of Pakistan just to repay its loans to China. Pakistan desperately needs an IMF emergency loan to avert a sovereign default since its external debt is $91 billion but its foreign exchange reserves are only $10 billion or a mere two months import cover. Historically, Pakistan’s military intelligence establishment has subordinated economics to strategic interests. The rift between Islamabad and Washington can only widen under Imran Khan since he, like all of civilian predecessors, has no control over the military’s jihadi clients or nuclear arsenal.

Pakistan has paid a heavy price for its deep state’s sponsorship of jihadi militants who have attacked embassies, hotels and other soft targets in India, Kashmir, Afghanistan and even within Pakistan – itself. In June, Pakistan was placed on the Financial Action Task Force’s grey list of countries that have failed to curb money laundering and the financing of terrorist organizations. The US may also deny Pakistan funding from the World Bank and the IMF. It will be impossible for the new PTI government to successfully engineer an economic turnaround in Pakistan unless it normalizes deeply strained relations with Washington. This in turn means Imran Khan must convincingly renounce his sympathy for the Afghan Taliban, the sworn foe of President Ashraf Gehani in Afghanistan.

Despite his Oxford education and playboy past, Imran Khan supports Pakistan’s blasphemy laws that mandate death sentences and has expressed visceral opposition to America’s ‘War on terror.’ He has threatened to shoot down US drones and disrupt NATO supply lines to help the Afghan Taliban. While I do agree with him on calling for an end to the US drone campaign, shooting down one will invite ten more – and a Western coalition force – to replace it. Khan believes that diplomacy via political recognition is the only way to end the Pakistan’s Taliban insurgency crisis. While this may be possible under Khan, it could further alienate Pakistan from its neighbors and allies. This would place Khan at a huge disadvantage with the Trump White House, which has criticized Pakistan’s government and deep state for providing sanctuary to the Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani network.

South Asia

The PTI’s record as the ruling party in the ethnic Pashtun majority Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province is not a good omen for Afghan-Pakistan relations under Imran Khan. While Khan has brought about numerous infrastructural and economic improvements that have enabled Pashtuns’ to have greater access to healthcare, education and housing, he’s made some distressing policy decisions as well. The PTI government funded the Darul Uloom Haqqania, the almamater of the Afghan Taliban elite, and opposed Malala Yousoufzai’s proposal to the provincial legislation that banned violence against women. Imran Khan also opposed General Musharraf’s post 9/11 alliance with President Bush’s “War on Terror” that overthrew the Taliban in Kabul and the Pakistan military’s offensive against jihadi militants in Swat and North Waziristan. This track record of Taliban appeasement makes Imran Khan anathema to the Tajik-Uzbek elite of the Afghan intelligence services and the fiercely anti-Taliban President Ashraf Ghani. Will Imran Khan jettison his pro-Afghan Taliban sympathies as the price of a new relationship with Kabul – and Washington? That is the core diplomatic dilemma of Khan’s ‘Naya Pakistan.’

It is doubtful if Imran Khan alone can improve Pakistan’s tense relations with its arch-rival India. The Pakistani military has historically opposed a political rapprochement with India as its own dominant position in Pakistani power politics is predicated on hostility to India. The ‘garrison state’ political culture of Pakistan means the Rawalpindi GHQ, not the elected Prime Minister, determines state policy in relations with India and Afghanistan. Prime Minister Modi, facing a general election in 2019, will not anger his hard-line Hindu nationalist vote bank with any diplomatic overreach to Imran Khan. It is doubtful if Imran Khan will defy his ‘deep state’ backers with a ‘kinder, gentler’ foreign policy with India. The tainted election and his Praetorian backers mean that the Prime Minister who promised ‘change’ to Pakistan will not be able to change the frozen status quo on both sides of the Radcliffe and Durand Lines. This is the tragedy of Pakistan’s international relations 70 years after the Great Partition.

The Middle East

During his campaign, Imran Khan caused quite a stir with Pakistan’s allies in the Middle East. Despite Pakistan’s close ties with Saudi Arabia, Khan called for greater bi-lateral relations with Iran and has even accepted a state visit invitation to meet with President Rouhani – which would mark Iran’s first Pakistani state visit since 1999 when President-General Musharraf met with Ayatollah Khameini to defuse bilateral tensions following his coup d’etat earlier that year. Khan’s plans may change following his visit with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman later this year as Riyadh needs Pakistan and it’s military establishment to support it’s anti-Iran, anti-Shia Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition – which is ironically lead by ex-Pakistan Army Chief of Staff General Raheel Sharif. With Pakistan having the largest standing army and being the only nuclear-armed nation in the Islamic world, Khan will have to proceed with caution in his balancing act with Saudi Arabia and Iran as it can not only determine Pakistan’s relationship with the West and the rest of the Islamic world, it may even impact domestic politics thanks to both nation’s immense sectarian support within Pakistan, itself.

It seems like at the end of every election, or coup d’etat, Pakistan is always at a cross-roads in its history. Despite his claims of a ‘new’ Pakistan, Imran Khan’s rise to power is no different from what has come before. It now remains to be seen what will become of Pakistan under Khan. Will he be able to revive the economy? Can he appease Pakistan’s disgruntled neighbors and allies? Most importantly, however, will Khan finish – or even survive – his term in office?