Do We Have Moral Obligations to Non-Citizens?

The argument that states have obligations to non-citizens is hardly novel. This has long been recognized by international refugee law, the laws of war, and other standard features of the international legal regime. Unfortunately, these arguments still have little practical currency to them. Most states feel that their primary-and often exclusive-obligations are towards their citizens (if that). There is a deep history behind this rather strange reasoning. Its deepest roots lie in the Westphalian consensus which dominated European thinking-if not action-on the relationship between state and citizens since the 17th century. The creation of the modern sovereign state in the 17th century, and the immense discursive and institutional authority granted to it, was an important precondition for the ideological formation of the nation; an idea which I believe still has altogether too much hold on our moral imaginations.

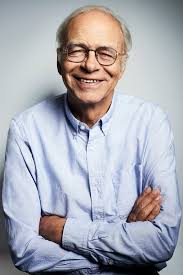

In this brief paper I will be making the argument that states have considerably obligations to look after non-citizens. The consequence of this would be that rich states would have substantial obligations to transfer considerable amounts of wealth to the developing world. I will begin by discussing the most persuasive argument to this effect; that made by the philosopher Peter Singer. I will then offer some critical observations on his position before previewing my own argument for this position.

Peter Singer of the Rights of Non-Citizens

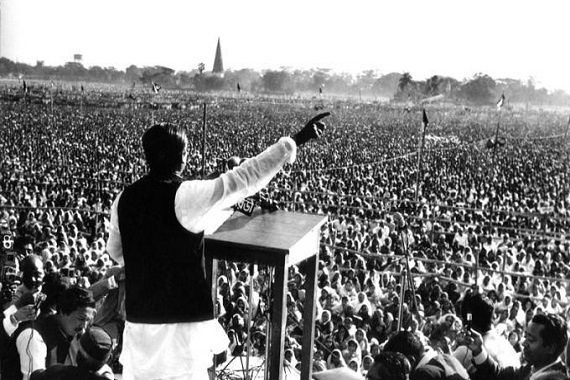

The most important and influential argument for expanding the rights of non-citizens and indicating where states have obligations to individuals beyond their borders is Peter Singer’s in his seminal 1972 article “Famine Affluence and Morality.” The article was inspired by the Bangladeshi war refugees. Beginning in March 1971 Bengali revolutionaries pushed for independence from West Pakistan, resulting in a brutal genocide that ended with the independence of Bangladesh by the year’s end. The exact figures on civilian deaths are hard to come by, with estimates ranging between 300,000 to as high as 3 million. During the conflict, almost 30 million of people were displaced, many of them Hindus. Many of these refugees left an incredibly violent situation only to find themselves deprived of food, medical attention, and shelter. Singer prefaces his article by noting that, despite the scale and depth of human need, most countries-including those of the wealthy Western world-gave very little aid proportionate to what was needed. Following the utilitarian argument, he goes on to argue that is seems apparent that “suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad.” Since it is clearly bad, if it is in our power to prevent it without sacrificing something of equal significant, we have a moral obligation to do so.

This brings us to the most famous part of the article. Singer asks us to consider the following provocative thought experiment. He asks us to imagine that we are walking past a shallow pond a see a child drowning in it. We are capable of wading into the pond, though the consequence would be that our clothes might get muddy. But Singer argues this consequence is morally insignificant next to the very bad result of the child drowning. Singer observes that, though the principle operating in this thought experiment seems uncontroversial, and consistent application of its logic to world affairs would be very radical. Firstly it suggests that proximity to need have no moral bearing on what we should or should not do. The only factor that is determinative is the significance of need itself. And secondly, it de-individuates our moral obligations by focusing exclusively on consequences. It makes no difference whether I, or millions of people, choose to do something. What matters is that the most significant needs are met.

Singer’s argument, if taken seriously as a moral position, significantly transforms the way we would think about our obligations to individuals living in distant parts of the world. As he puts it, he effectively effaces arguments concerning proximity and individual relations. If what matters is maximizing the happiness of all relevant moral actors in the world, then we have stringent obligations to commit our resources wherever they would do the most good. Here I will quote Singer at length, as he does a fine job of expanding on this position:

“The outcome of this argument is that our traditional moral categories are upset. The traditional distinction between duty and charity cannot be drawn, or at least, not in the place we normally draw it. Giving money to the Bengal Relief Fund is regarded as an act of charity in our society. The bodies which collect money are known as “charities.” These organizations see themselves in this way – if you send them a check, you will be thanked for your “generosity.” Because giving money is regarded as an act of charity, it is not thought that there is anything wrong with not giving. The charitable man may be praised, but the man who is not charitable is not condemned. People do not feel in any way ashamed or guilty about spending money on new clothes or a new car instead of giving it to famine relief. (Indeed, the alternative does not occur to them.) This way of looking at the matter cannot be justified. When we buy new clothes not to keep ourselves warm but to look “well-dressed” we are not providing for any important need. We would not be sacrificing anything significant if we were to continue to wear our old clothes, and give the money to famine relief. By doing so, we would be preventing another person from starving. It follows from what I have said earlier that we ought to give money away, rather than spend it on clothes which we do not need to keep us warm. To do so is not charitable, or generous. Nor is it the kind of act which philosophers and theologians have called “supererogatory” – an act which it would be good to do, but not wrong not to do. On the contrary, we ought to give the money away, and it is wrong not to do so.”

Singer’s argument is extremely powerful and in many respects persuasive. But he admits that if generalized aspects of it might appear counter-intuitive. Most people would argue that we have clear moral obligations to those proximate to us, and others which might flow from our political and legal connection to the state. But any actions we take pertaining to those less proximate, while they might be admirable, are none the less not morally stringent obligations. At best they are charity. But Singer is keen to point out that this constitutes a fundamentally arbitrary limitation on the horizon of our moral concern. Invoking the merits of the impartiality-what he will later term the point of view of the universe-Singer observes:

“The moral point of view requires us to look beyond the interests of our own society. Previously, as I have already mentioned, this may hardly have been feasible, but it is quite feasible now. From the moral point of view, the prevention of the starvation of millions of people outside our society must be considered at least as pressing as the upholding of property norms within our society.”

This argument demonstrates a deep problem with the way most of us engage in moral reasoning. Many of us think we have special obligations to those closest to us, and indeed I think we do. But this can also lead us to ignore and even dismiss the moral obligations we might have towards those far away, and whom might benefit a great deal more from the resources we would otherwise use to help those who are doing quite well. Trying to break out of this myopic form of reasoning and be more impartial is an extremely challenging task, and it isn’t clear to me that it could be accomplished by most ordinary human beings. Many of us are capable of demonstrating considerable care and altruism towards those who are closest to us. But we are often unwilling to do the same even towards those living within our local communities, let alone those who live far away and seemingly share little in common with ourselves. Singer’s thought experiment and discussion about the impartial moral point of view are a rejoinder to this; a staunch argument that if we wish to be truly rational in our moral outlook it might be time to move away from sentiment and towards looking more at the consequences of our actions for good and for ill.

Conclusion

Unfortunately I do not think that the adoption of such an impartial standpoint is entirely possible. Singer himself seems to admit this when he comments on that we must have a morality that does not deviate too far from the capacities of ordinary people. Singer characterizes this as an empirical issue, since it pertains to what individuals are willing to accept as morally binding and what goes too far. He then proceeds to argue against this position by maintaining that our sense for what is morally acceptable often flows from social norms, which can be changed and subject to critique, But I do not think this is a sufficient rebuttal. There is a deeper sense in which we need to demonstrate why morality should “matter” to people. It seems impossible to do this without appealing, at least in some respect, to their subjective embeddedness within a world of concrete human relations. Simple appeals to the quantitatively determined possibilities of doing the most good cannot overcome this gap. Indeed, Singer’s own thought experiment of the drowning child implicitly appeals to typical and sentimental human attachments for much of its rhetorical and argumentative power. What is therefore needed is to combine Singer’s arguments about the moral arbitrariness of proximity with an account of our moral obligations to non-citizens which is not so radically de-individuated.

In my forthcoming book Overcoming False Necessity: Making Human Dignity Central to International Human Rights Law, I make just such an argument. I claim that is we want to take seriously the idea that human dignity matters, this would necessitate rich states redistributing wealth to poor ones. This is for reasons that owe more to the liberal philosopher John Rawls than the Utilitarian Peter Singer: I argue that under conditions of fairness no person could agree that the arbitrariness of proximity and geography shod have such pronounced determinate impact on the dignity of individuals. International human rights law can play a major role in amplifying human dignity by ensuring wealthier state redistribute wealth where needed and coordinate the process of doing so to make sure everyone gets the most bang for their buck.