In the midst of political turmoil wracking our southern neighbours Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination and subsequent appointment to the Supreme Court, NAFTA renegotiation, and consistent turbulence within the Mueller investigation—Montrealers filled the streets to amplify local dissident movements. On October 7, 2018, the bilingual protest, Manifestation Contre le Racisme, or Demonstration Against Racism, garnered approximately 5,000 protesters, including students, parents, and members of 56 activist “organizations supporting the protest” according to the event’s website.

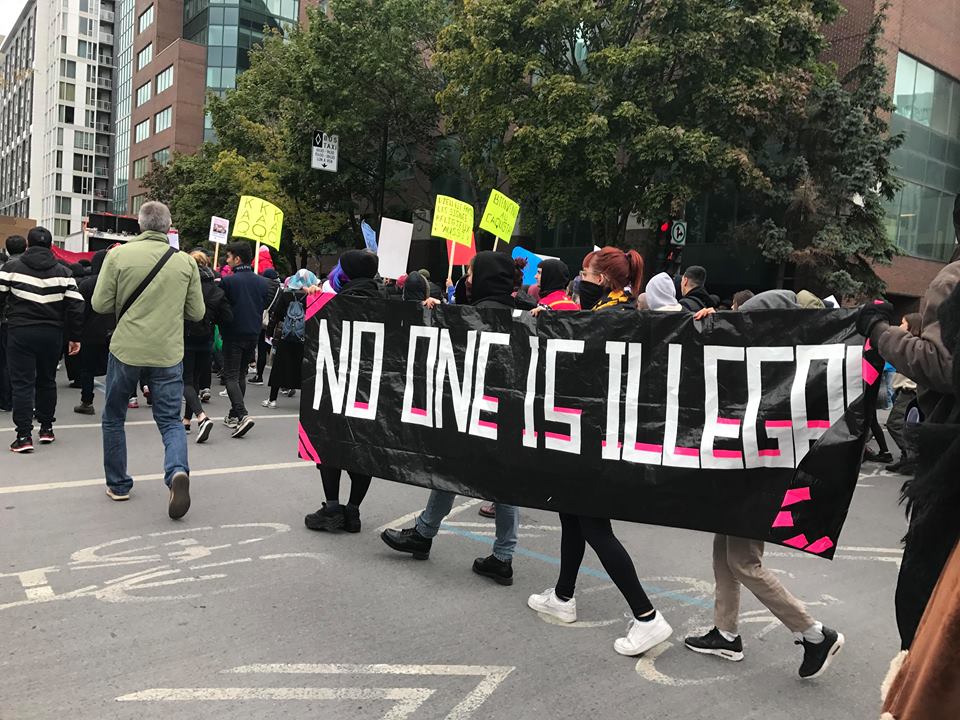

The movement was established in 2017 with the aim to mobilize against “hate and racism within Quebec’s public space, and [call] for a society without borders, based on solidarity and inclusion.” Powerful chants like “No hate. No fear. Refugees are welcome here” bellowed from speakers stationed atop a truck at the head of the seemingly endless march. Protesters energetically repeated the phrase in unison, pumping their fists and waving their posters. A brass band played upbeat songs near the front of the crowd and a drum corps donning red “Socialist Fightback” shirts kept up the energy further back. Periodically, individuals threw up a peace sign to indicate an acceptance of people from all backgrounds, regardless of race, gender, religion, political ideology, or citizenship status. In response, countless people responded by putting up peace signs of their own in what seemed like a wave sweeping through the vast crowd.

In stark contrast, several police cars and vans with blaring lights, an ambulance, and police on bicycles and in full body armour, followed the crowd throughout the more than two-hour march. To control the flow of people, police personnel formed lines along side streets and at intersections. There was a clear tension between protestors and police personnel. While maintaining their distance, protesters and organizers alike discussed racial profiling by police, the recent killing of Nicholas Gibbs by Montreal Police in the Nôtre-Dame-de-Grace borough, and chanted anti-police slogans in both official languages.

Last year, the same march weaved through prominent downtown streets like Sainte Catherine and Saint Laurent, gathering around 2000 marchers; only slightly more than a third of this year’s turn out. What explains such a substantial jump in participation after just one year? Perhaps it can be attributed to a consistent but noticeable rise of right-wing extremists across Canada, whose activities have rapidly expanded since 2015. Further, the conservative support base has ballooned in recent provincial elections in Ontario, with the Progressive Conservatives (PC) defeating fifteen years of Liberal leadership, and in Quebec, in which the centre-right, Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) under Premier Legault won the largest proportion (37.5 percent) of the vote on October 1st.

The protest’s rallying cry gained fervour following the CAQ win just one week before the protest, due to what organizers considered the party’s scapegoating and fear-inciting among immigrants “with the promotion of far-right proposals like lowering immigration levels, [requiring] an unnecessary values test [for documentation], or deporting people who fail French tests.” Many protestors traced similarities between CAQ’s problematic policy proposals and the conservative practices of the Trump administration.

CAQ Policies Questioned by Protestors

Organizers and protesters repeatedly emphasized the danger posed by the CAQ’s Quebec values tests and secularism. The party aims to promote laws like Bill 60 or the “Charter affirming the values of State secularism and religious neutrality and of equality between women and men, and providing a framework for accommodation requests.”

This “highly anticipated” charter came in response to debates regarding “reasonable accommodation” within a multicultural society. A discussion that originated in judicial jargon as early as 1985, “reasonable accommodation” refers to the legal requirement that “[e]mployers and service providers have an obligation to adjust rules, policies or practices to enable [individuals] to participate fully.” In the case of religious attire, that includes allowing individuals to wear visible symbols such as kippahs and hijabs. A failure to accommodate may be considered discrimination.

This debate is contentious in Canada because by treating certain groups differently, “reasonable accommodation” circumvents the fundamental principles of equality—“the absence of arbitrary legal privileges or distinctions of status”—within a liberal society, which is how many around the world perceive that Canada functions. Additionally, there have been several cases where individuals have sued their employers on the grounds of undue burden and discrimination. As such, the judicial system, a part of the state, intervenes within and regulates private business practices.

Despite opposition arising across all of Canada, objection to “reasonable accommodation” has been particularly poignant in Quebec. In 2007, the issue of discrimination bubbled over in response to a 2007 charter which officials called a “guide for immigrants” in Hérouxville, a small, rural town in central Quebec. Supporters used the statute as “a rallying point for those who felt Quebec was bending over backward to accommodate immigrants, losing its historical identity in the process.” Significantly, the leader of the CAQ predecessor, “the populist Action démocratique du Québec (ADQ),” Mario Dumont, mobilized support for the code as an example for the rest of Quebec.

In response, the Liberal provincial government formed the Bouchard-Taylor Commission to investigate “the accommodation issue”—whether minorities were adequately accommodated or if accommodation measures were going too far. The formal commission did not find any cause for concern, but growing support for policies aimed at curbing accommodation measures revealed that many Quebecois felt distrust towards immigrants and minorities.

For example, politicians in the Parti Québecois (PQ) introduced charters such as Bill 60 (2013), which would have allowed items, symbols, and articles of clothing that represented what the PQ considered acceptable embodiment of Quebecois values, all the while rejecting visible signs of religious diversity. This was clear in the original draft of Bill 60’s allowance of “the crucifix at the Québécois National Assembly, the cross on Mount Royal and the celebration of Christmas” as “part[s] of the Québécois cultural heritage” while simultaneously banning non-Christian religious symbols in public occupations. Bill 60 failed to pass in 2014, but similar laws arose in Quebec nonetheless. Bill 62, banning the burqa and niqab on public transport, in schools, and at medical appointments passed in the National Assembly in October 2017, but was subsequently suspended by a superior court judge.

The CAQ capitalized on the idea of banning religious symbols in their recent campaign, claiming that “[r]eligious signs will be prohibited for all persons in position of authority, including teachers.” Their platform was based upon the argument that “[a]fter 10 years of discussion [since the Bouchard-Taylor Commission] on the subject and on reasonable accommodations, it is more than time to act and adopt legislation clearly establishing the secularity of the state.” Protesters seized upon this view during the demonstration claiming that “[w]omen wearing hijabs have again been targeted, with the continued promotion of policies that would deny them work, including as teachers.”

“Someone asked me, “hey your origins are where from”? I said from Pakistan, my parents are from Pakistan […] but I can’t even go to Pakistan without a visa. What am I supposed to do then? […] I’m the same as you guys. It’s not the hijab that makes you Pakistani. […] It’s not my history. It’s my religion.”

Demonstrators disagreed with these policies on a variety of fronts. One participant, a female school teacher and Muslim told The McGill International Review (MIR) that whether she would be able to keep her job or not was uncertain. She explained that wearing the hijab was an individual choice—one that reflected her relationship with religion. Her dress was not an attempt to convert others to Islam through ostentatious religious symbols, but instead coexisted in harmony with all people. In fact, she claimed that some of the most damaging experiences she has had as a Muslim woman included being told “to go back to [her] country.” In response, she told MIR “I mean, what country do you want me to go to? I’m from England. My kids are born in Canada.” Her children, she said, questioned how they would be affected by threats of deportation and separation posed against their mother.

Another interviewee, UQAM professor, Dr. Abraham Weizfield, was himself Jewish, but stood in solidarity with Muslim protesters in his disapproval of Israeli, state-led oppression against Palestinians. He and many others participated in the demonstration to display grass-roots mobilization efforts to combat policies such as those promoted by the CAQ which seek to divide society along religious lines.

While many of those interviewed by MIR discussed CAQ policies, many also discussed larger scale issues pertinent to the wider Canadian context.

The Significance of Fascism

Before the protest, representatives from MIR spoke with Fehr Marouf, a member of Socialist Fightback, a socialist organization that functions as Canada’s branch of the International Marxist Tendency. Marouf, in a speech at the end of the demonstration on St. Laurent Street, argued that the election of the CAQ was not a surprise: it was only the “local expression of an international phenomenon of polarization that we can see everywhere in the world… to the left and the right.” Marouf argued that many people voted for the CAQ as a vote against the status quo, because ongoing economic struggles have meant that many people have seen their standards of living fall significantly. Still, Marouf argued the CAQ and Quebec’s right wing could not be countered with a “mushy liberalism” that deemed that there was no economic crisis, or that the crisis of capitalism was normal. Thus, Marouf argued that “We need a socialist answer…[because] the crisis of capitalism is caused by the capitalists themselves and their rotten system!”

Of the various organizations present at the self-proclaimed non-partisan march—like Socialist Fightback—the main coordinators included: Antifascist Montreal, Solidarity Across Borders, Food Against Fascism, and Anti-Capitalist Convergence. A common thread amongst these groups is their focus on systemic or structural rather than surface-level issues; for example, the rejection of fascism. This term is, admittedly, difficult to decipher, but encompasses the use of scapegoating or vilification of minority groups, a reliance on violence and terror, and “nationalist narrative[s] […] infused with racism, xenophobia, homophobia, and misogyny.”

Furthermore, fascism is not directly associated with any particular party and these components can be utilized within any ideology. In fact, its persistence and rise may be due to its undefined and malleable nature. However, research suggests that, historically, right-leaning parties have most often cultivated fascist sentiment and successfully mobilized it for political organization. Anti-Fascist Montreal stipulates that policies propagated by several right-leaning parties and political organizations in Quebec carelessly embolden fascist sentiment—at best—or intentionally capitalize upon it for political support at worst. To combat the threat posed by extremist ideologies, many have decided to take to the streets, rather than leave the battle to their elected officials.

Moving Forward

Following what many considered a failure of the electoral system to protect minorities, many persons, including but not limited to the head organizers of the event, spoke before and after the demonstration; emphasizing the idea that the new Quebec government would have to be fought on the streets, through mass organization.

Although the CAQ won the most recent round of elections, speakers reiterated that party does not fundamentally have the support of all Quebeckers. Several speakers denounced the CAQ for what they considered racist policies but stressed that, with or without the CAQ’s victory, racism was a systemic issue that had infiltrated Canadian politics at a fundamental level. Others who spoke went a step further, arguing that racism was a product of capitalism: to eliminate racism, therefore, capitalism itself would have to be eradicated.

Ultimately, the Demonstration Against Racism challenged the power of the CAQ, just as it challenged the recent rise of the right-wing throughout Canada and elsewhere. However, this protest was only the beginning. As organizers stressed, active dissidence and collaboration must continue long after the election cycle to make effective change. If demonstrators who showed up Sunday deem the protest as a one-time event, it may not be difficult for the CAQ government to implement the very legislation against which protesters spoke out.

Edited by Shirley Wang