Prosecution at last for Peru’s former President Alan García?

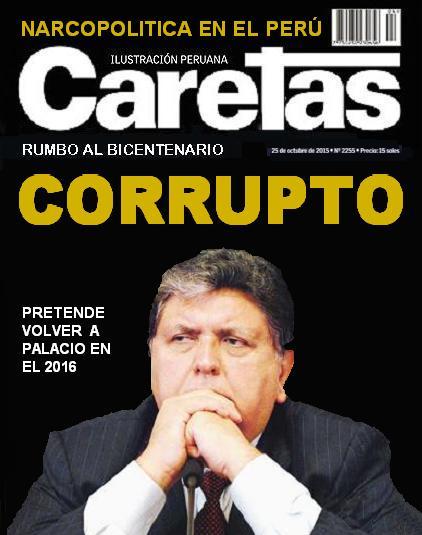

Former Peruvian President Alan García has sought asylum at the Uruguayan embassy in Lima following the Peruvian justice system’s decision to forbid him from leaving the country for 18 months. In Peru, García is widely regarded as a corrupt and egomaniac politician who is quite talented at hiding his illegal activities and bribing authorities. Surprisingly, the former president presented his request for asylum on the grounds that he was a victim of “political persecution”.

On November 22nd, García’s hearing on alleged bribes and money laundering in connection with Brazilian company Odebrecht was suspended for the second time. However, shortly after, District Attorney José Domingo Pérez requested an 18 month travel ban to ensure that García does not escape prosecution. The Second Court in Anti-Corruption Investigations approved Pérez’s request a couple of days later. In his letter to the President of Uruguay, Tabaré Vázquez, García claims that “in [his] country, laws and procedures are being manipulated for political interests like instruments of persecution”. However, there is a strong consensus in the Andean country that there is no political persecution at all. Martín Vizcarra, the incumbent President of Peru, spoke with President Vásquez of Uruguay on the phone to persuade him not to accept the asylum request. In a recent article from El País, Peruvian Nobel Laureate in Literature, Mario Vargas Llosa, similarly urges the Uruguayan government to consider the political price of supporting a “common criminal”. Despite the protracted waiting time for his trial, it is highly likely that Alan García will have to respond to his charges, once and for all.

Who is Alan García?

Alan Gabriel Ludwig García Pérez served as the President of the Republic of Peru twice: from 1985 to 1990, and then again from 2006 to 2011. A gifted orator, García started his political career at the age of 17, when he became a member of the Juventud Aprista Peruana (JAP), the juvenile organism of the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance – Peruvian Aprista Party (APRA), one the country’s major political factions at the time. In fact, García’s parents were important contributors to the party: his mother founded a base in Camaná, a province in southern Peru, and his father was imprisoned due to his ardent work as an aprista militant. During this period, the young Alan had the unique opportunity to listen to and become acquainted with many of the future leaders of APRA, such as Mercedes Cabanillas and Luis Alva Castro. These early formative experiences arguably had a great impact on his political profile.

In 1978, upon the completion of García’s studies in Sociology in Europe, Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre called him to return to Peru and run for the Constituent Assembly election. He won, and over the years brought the party to prominence, gaining the respect and admiration of his fellow apristas. His charisma and mesmerizing speeches helped him win the 1985 general elections with 45% of the votes. He was 36 at the time, making him the youngest president in the region. In fact, some people even called him “Latin America’s Kennedy”.

Quite unexpectedly, García’s first term in office (1985-1990) was catastrophic, to say the least. Throughout the five-year period, there was unprecedented hyperinflation of 2,200,200%. The García administration was so inept and irresponsible that the country’s GDP dropped 20%, and the average annual income of Peruvians fell to $720 USD. According to both the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics, and the United Nations Development Program, there was a 13% increase in the percentage of citizens living below the poverty line, rising to 55% by 1991.

On top of this, his government unsuccessfully attempted to nationalize the banking industry, and then complicated relations with the International Monetary Fund by limiting debt repayment to 10% of the Gross National Product. Coupled with the economic crisis, García’s government is also to blame for many human rights violations in its failed attempt to confront the menace of the Marxist-Leninist terrorist movement known as Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path). In 1986 alone, more than 200 inmates were murdered in the prisons of Lurigancho, El Frontón, and Santa Bárbara by military forces. Once his presidency ended in 1990, García moved to Europe and, even though there were numerous accusations of corruption against him, the justice system archived all of them. Indeed, as many political commentators maintain, both the human rights abuses and the corruption scandals that took place in this first period should have been enough for the justice system to convict him. Still, García somehow succeeded in leaving the country with impunity.

Following his defeat in the 2001 elections, García became President for the second time in 2006, this time with 53% of the national vote. Based on the close link between his opponent, Ollanta Humala, who later became president in 2011, and Hugo Chávez’s socialist regime in Venezuela, many skeptical members of the electorate ended up voting for García on the grounds that he represented “the lesser evil”. During this second tenure, the Peruvian economy experienced a great development due to the considerable increase in metal prices, producing a seven per cent GDP growth per year. Nevertheless, many people rightly criticized an increase in pollution and social conflict. Notably, in 2009, there was intense friction between the Indigenous peoples of the Peruvian Amazon and García’s government on account of oil reserves in the region: García called them “second-class citizens”. Unsurprisingly, he was accused of corruption and violations of human rights once again. And yet again, the investigations did not go anywhere.

The current investigation under District Attorney José Domingo Pérez currently only focuses on the alleged bribes between García and Odebrecht. Odebrecht is a corruption-tainted construction company from Brazil whose officials have bribed and coerced many presidents, including four of Peru’s former heads of state, and numerous businesspeople in Latin America. The District Attorney argues that Odebrecht bribed García for the long-awaited construction of the Metro Line 1, and that he illegally received the sum of $200,000 during his presidential campaign in 2006. However, many other formal accusations are in the making. Even though García claims that Brazil’s private industry federation paid him $100,000 for a single conference he gave in Sao Paulo, the investigation team of IDL-Reporteros established that Odebrecht paid him through Box Two of the company’s bribery department, thereby hiding the identity of the payer.

In the past few weeks, members of García’s party have tried to draw a parallel between his request for asylum and the political predicaments of Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, the historical leader of APRA. In 1949, Haya de la Torre requested asylum in the Colombian embassy in Peru. But, unlike the case of Alan García, military dictator Manuel Odría was persecuting Haya de la Torre, and he remained in the embassy for five long years. Furthermore, several international organisms, including the International Court of Justice at the Hague, agreed that military rebellion (which was the accusation against the political leader) did not constitute a common crime. To compare García’s request of asylum with Haya de la Torre’s is not only ridiculous but shameful: his ties with Odebrecht are clearly common crimes, and the travel ban poses no threat to his life. García’s actions clearly subvert the right to seek asylum owing to the fact that he is not the victim of ‘political persecution’, and that he has a long history of obstructing the law. If the Uruguayan government decides to grant him asylum, it will be a low point in the history of a country that has long cultivated democratic values. Fortunately, there are reasons to be optimistic: for the first time, Alan García has no scapegoat for his actions, and it seems he will have to face the imputations against him just like any other Peruvian citizen.