2018 Saw Influential Women Targeted in Iraq

Photo taken from Tara Fares' Instagram page, https://www.instagram.com/its.tarafares/?hl=en

Photo taken from Tara Fares' Instagram page, https://www.instagram.com/its.tarafares/?hl=en

A four-month period in 2018 saw a series of murders in Iraq from which a significant pattern emerged. The victims of these crimes were all high-profile young women, many of whom were known to speak out for womens’ rights and freedoms. These tragedies represent a significant loss to the community of outspoken women in Iraq. Highlighting issues of gender-based violence, these deaths serve to illustrate the threats faced by women who challenge traditional norms.

The trend seems to have begun with the death of beautician Rafeef Al-Yasiri, on August 16th, 2018. Al-Yasiri, also known as the “Barbie of Iraq”, was a well-known beauty expert and public figure who ran her own business, the “Barbie” Beauty Center. Preliminary investigations postulated that Al-Yasiri died in her home due to complications involving a medication she was taking. These conclusions may make this case seem unremarkable on its own, but it gains salience in the context of the suspicious deaths of women of similar backgrounds.

Only one week after Al-Yasiri passed away, another beauty expert, Rasha Al-Hassan, also died under suspicious circumstances. Al-Hassan was the owner and manager of the Viola Beauty Center in Baghdad, Iraq’s capital city. Preliminary cause of death was thought to be a combination of high blood pressure and other health issues, however, there is little official information available. Despite the preliminary findings in both the Al-Yasiri and Al-Hassan cases, rumours and speculation continue to swirl about their sudden demises, probably in large part due to the public nature of their work. A statement made by MP Faiq al-Sheikh Ali– “After the pilots, doctors, university professors and others, it is beauty centers turn now, from Rafeef to Rasha,” –seems to imply that someone is responsible for these deaths.

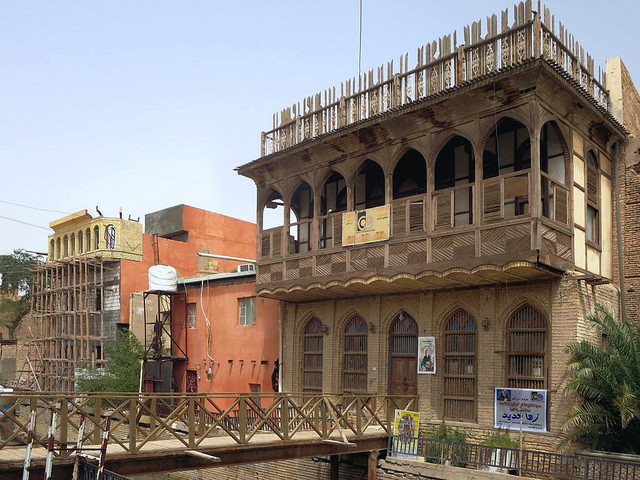

Unlike the cases concerning al-Yasiri and al-Hassan, there is very little question about Iraqi women’s rights activist Dr. Su’ad Al-Ali’s cause of death. Al-Ali was shot in Basra, Iraq, on September 25th, while waiting for a ride. A man standing with her was also wounded in the attack. Though the murder was caught on camera and an investigation is underway, the killer is still at large.

Al-Ali worked as the head of an organization called al-Weed al-Alaiami For Human Rights, which mainly focused on working for “women’s rights and demands” as well as “children’s rights and many activities for the revival of childhood.” In the days before her death, Al-Ali – acting as both the head of this organisation and as a public figure in her own right – had stated her support for political protests that were taking place in Basra at the time. The demonstrations were reportedly about “issues including poor infrastructure, contaminated water, and a lack of jobs,” as well as governmental corruption, all issues which would have affected the work that her organization does. Despite the fact that the protests did include some violent elements, Al-Ali’s murder is the “first such incident since the protests erupted this summer.”

Two days after Al-Ali’s death, Instagram model Tara Fares was also fatally shot. Fares was driving in Baghdad when a man reportedly walked up beside her car and shot her while she was still behind the wheel. Before her death, Fares was one of Iraq’s up and coming social media stars. She had approximately 2.7 million Instagram followers, and approximately 162 thousand subscribers on her Youtube channel. The content she released often showed the influence of Western fashion trends. This lead to threats against the model.

Fares’s story is similar to that of Qandeel Baloch, a social media star who was also known as “Pakistan’s Kim Kardashian.” In 2016, Baloch’s brother was convicted of murdering her in a so-called “honour killing.” Baloch’s brother admitted to the crime in a video where he stated that she had brought “dishonour” onto their family. Although Baloch was from Pakistan, both Fares and Baloch were influential women who promoted non-traditional lifestyle choices, gaining their fame through the use of social media platforms and provocative, modern rhetoric.

Many striking similarities exist between Al-Yasiri, Al-Hassan, Al-Ali, and Fares and the circumstances of their deaths. Foremost, most of these victims were somehow involved with the beauty industry, in fighting for women’s rights, or both. Additionally, none of the victims adhered very strictly to traditional cultural norms (arguably as all of the women were public figures). An incredibly short timeline and a similar modus operandi, specifically in the cases of Al-Ali and Fares, add another layer of coincidence to the situations. When the former Prime Minister of Iraq, Haider Al-Abadi, (who was in power at the time) ordered an investigation into Fares’ death, he specified that investigators would look into the possibility of the deaths being linked. The former PM also stated that the deaths “give the impression that there is a plan behind these crimes.” However, no evidence has been found to support these suggestions.

Resources are available to women in Iraq at risk of violence, but they are often inadequate. There do exist support systems, shelters, and advocacy groups for women in Iraq. Providors of this aid, however, are faced with serious obstacles. For instance, the hidden domestic abuse shelters run by activist Yanar Mohammed are secret due to the risk presented by the individuals the women are fleeing from, including spouses or family members. Additionally, the government has not made the shelters officially legal and they are generally viewed with “suspicion.” Understandably, these places tend to mostly deal with the issue of domestic or familial violence as opposed to targeted murders with possible political motives, seeing as nearly half of married women in Iraq have been exposed to some kind of spousal abuse. In Iraq, OCED data shows that 55% of Iraqi women agree that “a husband/partner is justified in beating his wife/partner under certain circumstances.” As a result of this cultural attitude, daily life for many women in Iraq is precarious. Diverging from tradition is not well regarded, as can be understood by the way both Fares’ career and Mohammed’s system of shelters have been critiqued. Additionally, OECD data shows that Iraqi laws pertaining to rape, sexual harassment, and domestic violence do not protect women adequately.

Nadia Murad, a Yazidi woman from Iraq who survived the “systematic enslavement of Yazidi women” by ISIS, is one of two Nobel Peace Prize winners of 2018. But while global attention to gender-based violence in Iraq has increased, the situation for outspoken activists as well as average civilians in Iraq remains treacherous. Despite the efforts made by activists like Yanar Mohammed, the Madre organization, and even al-Ali’s group al-Weed al-Alaiami For Human Rights , 2018 shows us that there remains a long road to travel in the fight for gender equality and against gender-based violence in Iraq.