Bolstering Human Rights: A Brick in the Road

Last month, Amnesty International released their annual 2014/15 report on the state of the world’s human rights. Much like that of Human Rights Watch, another major human rights non-governmental organization (HR-NGO), the report concludes that the past year has been a devastating one for human rights protection.[1]

In light of the front-page events of the last year, this comes with little shock value. The Syrian conflict alone has now claimed over 200,000 lives, displacing an estimated 11.6 million Syrians. In addition, the rise of ISIS has brought a new human rights abuser to the region. Even in the presence of international forces, the Central African Republic has seen over 5,000 die in sectarian violence, a majority of them civilians. The Palestine-Israeli conflict saw over 1,500 Palestinian civilians killed by Israeli forces, but also the indiscriminate fire of rockets toward Israeli civilian areas by Hamas. In the United States, a Senate Intelligence Community report released in late 2014 provides evidence of previous CIA interrogation practices amounting to torture. Concerns were also expressed over repeated instances of law enforcement agencies’ excessive use of force. Venezuela saw violent government repression of citizen protests, scores of arbitrary detentions and denial of access to doctors and lawyers for those detained. The list goes on.[2]

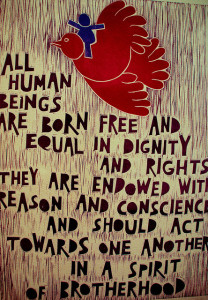

What remains clear in all this is that we do a poor job of protecting the basic rights of all humans that were enumerated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights over 66 years ago.

This is largely because the institutions created to uphold these rights fail us. Organs of the UN, such as the Security Council, are continually undermined by those states that ascribe very little importance to human rights protection. Often human rights abusers themselves, these states fear creating a precedent for human rights based intervention in their own internal affairs. This remains most apparent in the cases of China and Russia, two grievous human rights offenders, who have now vetoed resolutions before the Security Council for intervention in Syria on four separate occasions.[3] The effect of these vetoes has also extended to neutralizing the ability of the International Criminal Court (ICC) to protect human rights.[4] This severely damages whatever powers the ICC previously held to denounce and deter human rights abuse by state officials by setting a precedent that officials of states (with the right ties to Security Council members) can remain immune to the dictates of the court.

To fix these problems, both transformative reform of the Security Council – proposed in Amnesty’s report – and stunning changes in the way the most abusive states are held accountable to their people and the international community are necessary. But to only point the finger outside of the developed countries of the west ignores a host of western contributions to structural problems, missing commitments, and human rights abuses that occur in our world’s most liberal democracies.

Even states with strong histories as human rights defenders, like Canada, have plenty of room for improvement in human rights. Canada has yet to sign the UN Arms Trade Treaty, or the UN Optional Protocol to the Convention Against Torture.[5] While Canada has domestic statutes to protect against torture, these have not prevented it from taking actions that have been criticized by the UN as complicit in torture.[6] Additionally, Canada has been criticized for rejecting the calls of 40 countries, including progressive nations like Switzerland, Norway, and New Zealand, at the UN Human Rights Council to review violence against aboriginal Canadian women. Other countries with questionable human rights records such as Russia, Belarus, Cuba and Iran have also joined in this criticism.[7]

The United States presents an even more serious example of a liberal democracy with particularly vast room for growth. In the last decade, the United States been condemned for a long list of human rights abuses, including allegations of torture, refusal to abandon the death penalty, and indefinite military detentions in Guantanamo Bay, all of which violate the Universal Declaration.[8] In light of this it remains unsurprising, but equally problematic, that the United States has only ratified 5 of the 18 International Human Rights Treaties.[9]

This is not to ignore the reasons posited by governments for the actions they take. Governments such as Canada’s, by most accounts, are not shirking responsibility because they show inclination toward the to ability to commit systematic human rights abuse. Rather, they are seeking to balance commitments to human rights with a host of responsibilities to uphold the rule of law, respect individual freedoms, and ensure continuing good governance. In the case of the Arms Trade Treaty, for example, Canada has refused to sign because of the potential possibility that the treaty may affect lawful firearms owners in Canada.[10] However, when human rights are at stake, the choice of priorities in locating this balance is suspect indeed, and speaks to the need to develop stronger norms that stress human rights as a priority.

If our liberal democracies have commitments to human rights protection that are weaker than many of us would like to believe, it is because the norms of our societies do not yet sufficiently stress human rights protection to a high enough degree. Further norm development is necessary then within countries like Canada if institutions protecting human rights are to be bolstered. Giving states with questionable human rights records, such as Belarus, Cuba, Iran, and Russia, opportunities to criticize a country like Canada, as mentioned above, will only weaken the perceived need for them to uphold human rights and adhere to international norms in order to deserve respect from the international community.

This is where the importance of HR-NGOs comes into play. HR-NGO’s, like Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, provide a powerful segment of civil society committed to, not only fighting grievous human rights abuses abroad, but also shoring up the commitments of a state’s citizens to human rights protection. This has the potential to increase the priority that the state ascribes to human rights when forming policy to find the balance alluded to above. As Finnemore and Sikkink’s norm dynamics framework suggests, what these groups are really doing is providing organizational platforms for norm development, helping norm entrepreneurs battle existing norms.[11]

This is where the importance of HR-NGOs comes into play. HR-NGO’s, like Amnesty and Human Rights Watch, provide a powerful segment of civil society committed to, not only fighting grievous human rights abuses abroad, but also shoring up the commitments of a state’s citizens to human rights protection. This has the potential to increase the priority that the state ascribes to human rights when forming policy to find the balance alluded to above. As Finnemore and Sikkink’s norm dynamics framework suggests, what these groups are really doing is providing organizational platforms for norm development, helping norm entrepreneurs battle existing norms.[11]

An example of this can be found in the work of Amnesty International’s recent campaign to free Saudi blogger Raif Badawi. Mr. Badawi’s sentence for operating a liberal blog promoting Thomas Paine’s view of the “adulterous connection between church and state”[12] includes a decade in prison and 1,000 lashes. Amnesty has stressed that this sentence violates both the Geneva Convention and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, both of which prohibit torture and cruel or inhumane treatment. To date Amnesty has inspired over 1.1 million online petition actions to put pressure of the Saudi state to rethink their treatment of Mr. Badawi.

Though the most immediate and pressing goal of this campaign is without a doubt to protect the victim, the campaign is also directed towards norm creation. By focusing on the plight of an individual victim, existent domestic norms about the persuasiveness, or lack-thereof, of a strong stance against torture are challenged. Presenting individual cases humanizes the norm by putting the face of a victim behind it, bolstering the case for making the prevention of torture a priority.

Additionally, Amnesty takes the vague norm of human rights protection and gives it specificity. According to Finnemore and Sikkink, this is a necessary step in norm development, as vague norms remain particularly difficult to implement.[13] Much like the Millennium Development Goals gave the goal of poverty eradication specificity, giving human rights protection norms specificity by focusing on different aspects, like torture, is a means to provide more effective paths to internalization by members of the public.[14]

It is this type of norm development that is necessary within countries like Canada if human rights protecting institutions are to be bolstered. Weak domestic norms reduce the pressure needed to make the necessary commitments to minimizing spaces where human rights flourish. Illicit arms sales and complicity in torture present two of the most striking examples of this. Not making human rights a priority also creates space for abusers to discredit liberally democratic states commitments to human rights. This makes the norms that uphold human rights less persuasive on the marketplace of ideas and diminishes these states’ normative authority to denounce gross abusers. Therefore, strengthening domestic norms must first occur if such norms are to be pursued on an international stage. HR-NGO’s present a platform for doing so, and thus deserve our support and attention. While the path to better international institutions must indeed be multi-pronged, and will surely not happen by improving liberal democracies alone, such improvement remains a key brick in the road.

____________________________________________

Bibliography:

[1] Amnesty International, Amnesty International 2014/15 – The State of the World’s Human Rights, (London: Peter Benenson House, 2015).

Human Rights Watch, World Report 2015 (New York: Seven Stories Press, 2015).

[2] Amnesty International.

[3] United Nations (2015, February 15) Security Council Veto List. Retrieved from U.N. Dag Hammarsköld Online Library: http://research.un.org/en/docs/sc/quick

[4] Russia and China veto U.N. move to refer Syria to international criminal court. (2014, May 22) Retrieved from The Guardian Online: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/may/22/russia-china-veto-un-draft-resolution-refer-syria-international-criminal-court

[5] United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. (2015, March 1) Status of Ratification Interactive Dashboard. Retrieved from U.N. Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights: http://indicators.ohchr.org/

United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. (2015, March 1) The Arms Trade Treaty. Retrieved from U.N. Office for Disarmament Affairs: http://www.un.org/disarmament/ATT/

[6] Canada accused of complicity in torture in UN report. (2012, June 1) Retrieved from CBC News: http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-accused-of-complicity-in-torture-in-un-report-1.1166597

[7] Canada rejects UN call for review of violence against aboriginal women. (2013, September 19) Retrieved from The Globe and Mail: http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/canada-to-reject-un-panels-call-for-review-of-violence-on-aboriginal-women/article14406434/

[8] Amnesty International.

[9] United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights.

[10] Canada holds off on arms trade treaty even after U.S. Signs. (2013, September 25) Retrieved from CBC News: http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/canada-holds-off-on-arms-trade-treaty-even-after-u-s-signs-1.1868230

[11] Finnemore M, Sikkink, K. “International Norm Dynamics and Political Change,” International Organization (The MIT Press) 52, no. 4 (Autumn 1998): 887-917.

[12] Hugging the Saudi Floggers. (2015, January 24) Retrieved from The Economist: http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21640352-america-should-reconsider-its-cosy-relationship-saudi-arabia-hugging-saudi

[13] Finnemore and Sikkink.

[14] Fukuda-Parr S, Hulme D. “International Norm Dynamics and ‘The End of Poverty: Understanding the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs)’”. WPI Working Paper 96, Manchester: Manchester University (2009). Available: http://www.eadi.org/fileadmin/MDG_2015_Publications/fukuda- parr_and_hulme_2009_i?nternational_norm_dynamics.pdf. Accessed 2 March 2015.