Is There an End in Sight for the Afghan Conflict?

The Past, The Present and The Uncertain

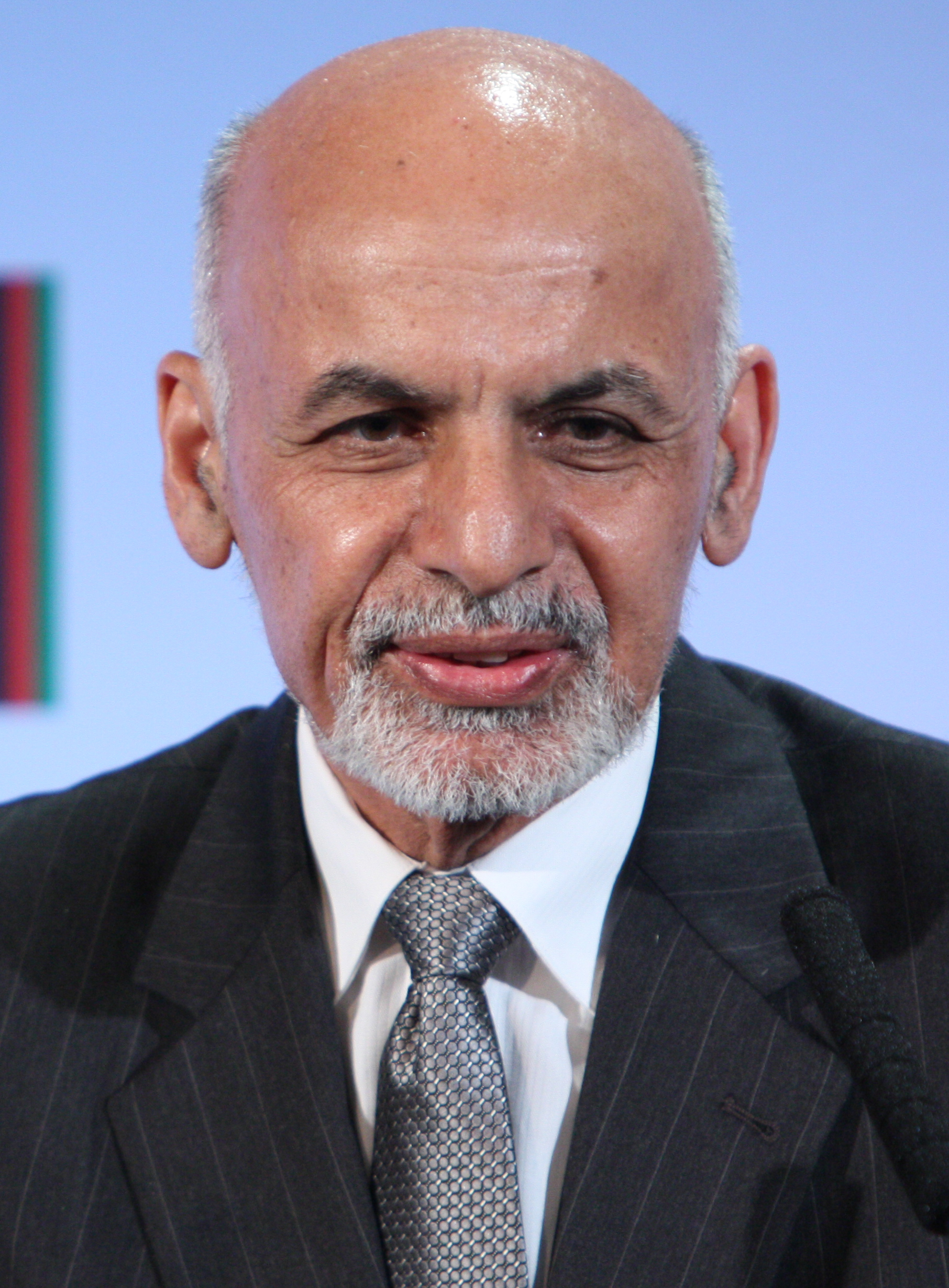

President Ghani meeting with President Trump

President Ghani meeting with President Trump

On 7th October, 2001 the United States administered the beginning of what would become a financial black hole as well as a military quagmire — the invasion of Afghanistan. A conflict that began as an effort to topple a government of extremists that was providing safe havens to terrorists has progressed into a grueling war. Now, nearly two decades since the start of the conflict, a resolution for peace remains elusive. The current situation is still as precarious as when the conflict first began with a fragile central government and a resilient insurgency, while recent peace talks have sparked more questions than answers. To understand the various nuances of this conflict and the direction in which it is heading, it is important to first understand the complex history of Afghanistan.

The Origins of The Insurgency

During the height of the Cold War in the 1970s, political unrest in Afghanistan among and against the ruling communist party, the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan under Hafizullah Amin, eventually led to a Soviet-led invasion in 1979. Almost immediately, to counter Soviet influence, the United States along with regional allies at the time Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, funded and armed a group of Sunni Islamist militias collectively known as the Mujahideen. Forging a resolute resistance through sustained guerrilla warfare, the Mujahideen successfully forced the Soviets to retreat from Afghanistan in 1989, leaving the Afghanis to fend for themselves. The government subsequently collapsed three years later in 1992.

Following the toppling of the Soviet-backed regime, the Mujahideen failed to reach a consensus on a new government. The coalition of Islamist militias that had united to rid the country of the Soviets collapsed and a decade-long civil war broke out among the splintered factions of the Mujahideen. The victors were a group that emerged in 1994 the midst of the civil war— the Taliban. The Taliban gained prominence on a pledge to establish an Islamic society and eliminate corrupt warlords. Following their victory, the Taliban assumed power but were only recognised as a formal government by Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and the UAE.

On September 11, 2001, terrorist organisation Al-Qaeda launched a series of attacks against the United States, resulting in almost 3,000 deaths. Before and after the attacks, Al-Qaeda was granted a safe haven by the Taliban in Afghanistan. The two groups were allied in their shared Islamist mindset and their mutual connection to the Mujahideen in the 1980s. Immediately after the attacks, President George W. Bush demanded that Al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden be handed over but the request fell on deaf ears. Subsequently, in October 2001, the United States along with other NATO members including the United Kingdom and Canada, invaded Afghanistan to combat terrorism and so began the “War on Terror”.

Following the 2001 invasion, the United States’ presence in Afghanistan steadily rose. It peaked in 2010 with over 100,000 troops on the ground, but has since gradually declined to 14,000 following a series of withdrawals. Unfortunately, attempts to allow Afghan security forces to take over and play a leading role in the fight against the Taliban have only resulted in gains for the insurgency. Today, the Taliban hold more territory than ever before.

Where Things Stand

Despite American efforts to resist and eradicate the Taliban’s power in Afghanistan, the Taliban now control and/or contest up to 70% of Afghan territory, which is far more than at any other point since the conflict began. The Trump administration has increased the number of targeted air force operations against the country, and with the high number of civilian casualties, anti-US sentiment has drastically increased across the frustrated, war-torn nation.

“Attempting to control rural areas in Afghanistan always eventually ends up boiling down to simple personal survival. No strategic gains are accomplished, no populace is influenced, but the death or dismemberment of American and Afghan troops is permanent and guaranteed.”

Evan McAllister, former reconnaissance Marine staff sergeant and sniper

The US effort to assist and facilitate in developing Afghan armed forces capable of successfully combating the Taliban forces once the US withdraws has achieved limited success. Afghan forces suffered record-high casualties in the past three years – 28,000 members of Afghan security forces have been killed – and currently control the smallest amount of territory since the conflict began.

As a result of the Trump administration’s promise to limit intervening in conflicts abroad and the financial and military exhaustion from a two-decade long war, the US is in search of an exit strategy. President Trump has been considering a partial withdrawal of approximately half the forces currently stationed in Afghanistan. A primary concern among experts is the potential power vacuum that may arise from a sudden withdrawal of this magnitude, especially given what occurred in Iraq in 2011, which eventually led to the rise of ISIS. Before he resigned, former US Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis advocated for a sustained presence. He stated, “If we leave, with 20-odd of the most dangerous terrorist groups in the world centered in that region, we know what will happen. Our intelligence is very specific. We will be under attack.” The decision to withdraw, however, appears to be supported by the general public with polling showing that 61% of Americans support military withdrawal in Afghanistan.

“Their (Afghan forces) losses have been very high. They are fighting hard, but their losses are not going to be sustainable unless we correct this problem. If we left precipitously right now, I do not believe they would be able to successfully defend their country”

The United States has maintained a longstanding policy of ensuring that any peace process be “Afghan owned and Afghan led.” However, in October 2018, the Trump administration broke away from this policy by engineering a meeting between US officials and Taliban representatives in Doha without any representation from the Afghan government. The meeting was held to discuss potential ways of putting an end to the conflict but this has proven to be difficult so long as the Taliban remain as powerful. The objectives of the Taliban are straightforward: firstly, they wish to eliminate foreign invaders, notably the US, and secondly impose their strict and uncompromising version of Islamic Sharia Law over all of Afghanistan. The Taliban have made it abundantly clear that they are not interested in negotiating with the Afghan government and have rejected all negotiation attempts made by Afghan President Ashraf Ghani.

The Vying Stakeholders

The strength of the Taliban and any hope of peace depend not only on the internal struggle between the insurgency and the government but also on the external influences in the conflict. The United States has alleged that the Taliban are currently benefiting from external support from Pakistan, Iran and Russia.

Pakistan is believed to have been supporting the Taliban since its inception in the 1990s. Although the US and Pakistan joined together to fund the Mujahideen to remove the Soviet forces in the 1980s, Pakistan’s continued support of the insurgent forces has strained relations. The Pakistani military initially supported the Taliban as a sympathetic government in Kabul and, after the 2001 invasion, maintained their support in an effort to create instability in Afghanistan and solidify their geo-strategic importance in the War on Terror. Pakistan has a formal doctrine of “Strategic Depth” in Afghanistan, which stems from the fear that Pakistan’s border with India lies too close to key Pakistani cities. This allows Pakistan to use Afghanistan as a rallying point in case of conflict with India, as well as allow for a greater focus on military assets at the country’s eastern border facing India. Nonetheless, Pakistan’s leverage over the Taliban makes it a necessary facilitator of any long term peace initiative. On 17th January, President Ghani called Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan to thank Pakistan for its role in facilitating peace talks.

Pakistan’s long term adversary, India, has also been increasing its influence in Afghanistan through developmental projects as well as establishing closer ties with the Ghani government. A large part of the Indian strategy is to ensure that terrorism is kept away from its borders in Kashmir as well as limit Pakistan’s influence in Afghanistan.

The United States has also accused Iran and Russia of supporting the Taliban. Anthony Cordesman, a national security analyst at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, states that Tehran is forging ties with the Taliban as a contingency plan for if the group seizes further control after the United States withdraws. Cordesman also mentions that Iran views the Taliban as a lesser of two evils when compared to ISIS in Afghanistan; the Taliban are seen as a nationalist movement whereas ISIS holds aspirations of becoming a regional Sunni Muslim caliphate. Russia bypassed Afghan authorities and held peace talks in Moscow with Taliban leaders and other neighbouring states in November 2018. The lack of protocol exhibited by these talks angered the Ghani administration, who later stated that Moscow could risk jeopardizing the US led peace talks with the Taliban.

“We’ve had stories written by the Taliban that have appeared in the media about financial support provided by the enemy. We’ve had weapons brought to this headquarters and given to us by Afghan leaders and said, this was given by the Russians to the Taliban. We know that the Russians are involved.”

General John Nicholson (retired) former commander of NATO forces in Afghanistan

What the Future Holds

Despite certain promising developments, after forty years of endless conflict, peace continues to remain a distant hope for Afghanistan. The resurgent Taliban forces appear to hold more power today than at any other point since the War on Terror began. The withdrawal of American forces would likely open Afghanistan up to further exploitation from other actors, both inside and outside of the country’s borders.

Although an effective solution in Afghanistan has yet to be developed, one thing remains clear: bombs and bullets have failed to yield a desired outcome for the conflict-riddled nation. Instead of continuing to fight a seemingly never-ending war, Afghanistan, their allies, and their enemies should re-focus their energy on hosting productive peace talks to truly put an end to the conflict once and for all.

Edited by Allegra Mendelson and Sarie Khalid