East Africa and the Drug Trade: A Growing Threat with Little Intervention

Shedding light on the spillover effects of transnational drug trafficking in East Africa

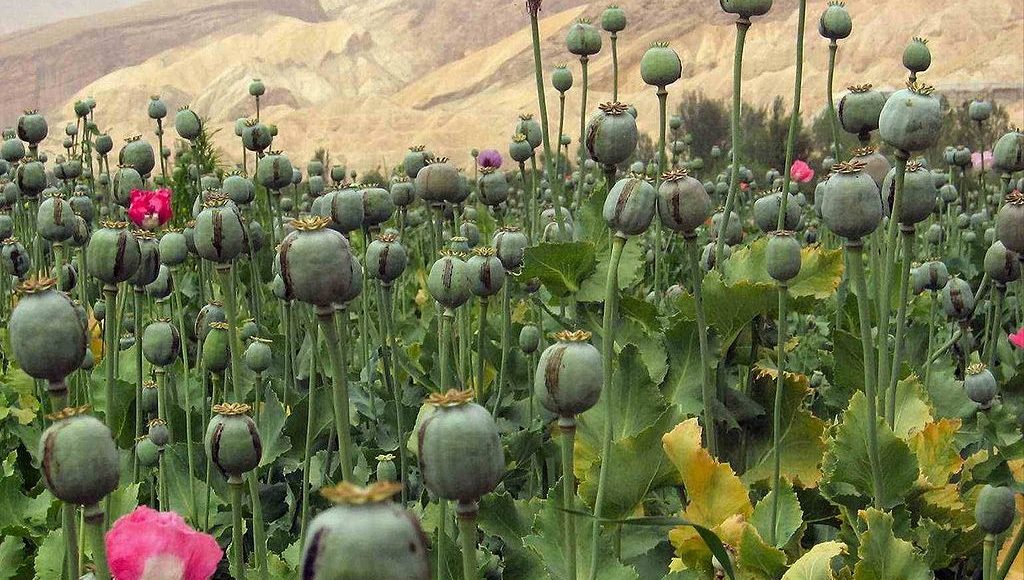

Opium poppy field in Afghanistan, the birthplace of the largest illicit opium production in the world.

Opium poppy field in Afghanistan, the birthplace of the largest illicit opium production in the world.

While there was a time when the quasi-legality of khat or cannabis was the main concern regarding the regulation of drugs in Africa, contemporary international drug trafficking has taken the issue to a completely unprecedented level. The transnational crime has been evolving at a rapid rate with adapted techniques to survive in the growing counter-narcotics world of today, one which combines efforts not only to reduce abuse of illicit narcotics, but the social harms associated with use, production, trafficking and more. Since Northern American countries and the European Union have tightened their measures to deter the trade, traffickers have resorted to Africa as an effective gateway for drugs. The Balkan route or commonly called the “southern route” begins in Afghanistan where 90 percent of worldwide opioids are produced, and travel through the East-African Indian ocean where Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania and finally South-Africa are the common transit points towards Europe. Particularly, the Balkan route has gained the attention of the international community since 2010 because of its large-scale heroin trafficking.

Due to the increasing availability of drugs from around the world being sold at cheaper prices in African markets, a wider demographic of individuals have access to them. Not only has the quantity of trafficked drugs increased, but the variety has expanded, allowing heroin, cocaine, opium, sedative-hypnotics and their compound forms to become some of the recent developments on the continent. According to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime in 2016, the flow of drugs was one of the most alarming threats in Africa. Even more worrisome, however, are the numerous negative externalities on the population which require urgent countermeasure programmes to avoid irreversible damage. Paying special attention to East African countries, the negative consequences of drugs on governmental organization, the healthcare system, its relationship with HIV/AIDS and gender imbalances deserve careful consideration.

The correlation between corruption and drug trafficking is high and observable in various forms. Many drug trafficking groups in very low-income countries tend to be more prosperous than their governments. As a result, they buy their protection from the state and continue to expand their businesses with the government’s tacit consent. A study conducted by the International Peace Institute in Kenya shows that trafficking groups penetrate the government and subvert them, influencing politicians to actively take part in the organized crime. Beyond tacit consent, certain political leaders endorse and control the flow of illegal drug markets. Guinea Bissau, referred to as “narco state” by the UN is home to the largest drug market in Africa, where military coups are allegedly diversions for drug trafficking and where elites enjoy protection from arrest due to state’s political fragility.

Second to Guinea Bissau in the drug trade is Mozambique, where 2009-2010 US reports revealed that the top two businessmen were protected by former president Guebuza. The relationship between smugglers and the state is characterized by frequent political donations from traffickers in exchange for the state’s protection. In one case, hundreds of motorbikes with heroin in the petrol tanks passed, free from detection at the port of Nacala, Mozambique.

Although there are many African governments who collaborate in the creation of counter-narcotic programmes, when the state is corrupted and involved in the drug trade, the country becomes a notorious point of transit, creating a favorable environment for the expansion of narcotics trade as it extends to neighboring countries. As a result, the efforts of the other states are undermined. Additionally, political corruption makes it difficult, if not impossible, for civilians to report drug crimes. Without a reliable government, drug prevention programmes cannot be enforced since the fundamental organ that is charged with upholding the rule of law is impaired.

The link between drug trafficking and the healthcare system has roots in political structure as well. Most African healthcare systems already face organizational issues as the systems are decentralized, ineffective and poorly adapted to treat high numbers of patients and a wide variety of diseases. Such failures are correlated with the government’s inability to account for an effective allocation of resources to public institutions since it is responsible for funding the system. Where healthcare workers are minimally supervised, they enjoy unlimited freedom. A growing problem in East Africa is that of a drug-consuming health force for which the literature justifies with manpower shortage, prescription privileges, leading to unaccounted self-medication and professional invincibility, where workers are confident their knowledge cannot lead to addiction. Hence, the greater availability of drugs due to trafficking adds on to the already strained system as the health force experiences substance abuse magnifying the poor quality in health supply. A study conducted in Kenya demonstrates that healthcare workers (HCW) have higher substance abuse rates than the general population. Healthcare workers who had consumed three months prior to the study explained having strong desires to consume again. There are numerous consequences including lower productivity, higher rates of absenteeism which is a primary determinant of healthcare quality, “drug leakage”, the robbery of medical supplies by HCW, bribes for promotions and jobs, informal payments to HCW and poor ability to intervene on the population’s substance abuse. Clearly, an ineffective healthcare system cannot adequately treat patients, much less drug addictions.

Of all the implications of drug trafficking, its relationship with the prevalence of HIV has the greatest direct consequences on public health. Because HIV spreads with very high efficacy when driven by drug abuse, it is known as a twin epidemic. It is the fastest growing cause of the immunodeficiency virus considering more than four million patients in over 114 countries have drug-driven HIV. Indeed, drug users who inject substances are 22 times more likely to contract HIV compared to the general population. Furthermore, substance abuse for diagnosed patients interferes in the treatment process, contributes to the progression of the virus and ultimately increases the likelihood of AIDS’ development. The most significant negative externality is congenital HIV which globally accounted for 160,000 children in 2016, including 438 babies born with HIV per day.

To reduce rates of drug-driven HIV, one must first address drug abuse. On the African continent, more than 2.5 tonnes of heroin are consumed annually and the highest consumption comes from Tanzania. There, addiction rates are high, but the legal system treats it as a criminal offense which justifies the stigma, preventing patients from seeking proper rehabilitation. This increases marginalization and consumption in high-risk environments. Clinicians and health professionals commonly employ the abstinence method to treat addictions; patients have to abruptly stop consumption under the supervision of health experts. However, studies demonstrate the method has poor success rates. Observations point to the radical nature of the treatment to explain its failure; addiction is not voluntary, rather it is chronic and progressive. Thus is requires multi-dimensional treatment (psychological, emotional and physical) over a long period of time. To this end, it is moderation—not abstinence—that would lead drug users toward sustainable recovery. To counter the growing epidemics, Tanzania has become a pioneer in Sub-Saharan Africa for the development of a health intervention that offers a drug substitution with therapeutic elements for treating addiction: “The Methadone Programme.” Methadone, taken in the form of syrup, inhibits the effects and cravings for opioids. According to WHO, it is the most effective programme to treat heroin addiction. While Tanzania has implemented it, many African states refuse to introduce it because of its necessary financial investment and the stigma surrounding drug addiction.

Of all the challenges that drug users face regarding treatment, discrimination, the stigma and more, women who consume face unique obstacles due to their marginalized political and economic status. Intersectionality, as coined by Crenshaw is the convergence of different forms of inequalities, creating obstacles that are not understood within traditional social justice advocacy. Women’s experience with drug-driven HIV is significantly different from a male’s perspective because they endure intersectional consequences of drug trafficking with unequal gender treatments. Women between the age of 10-24 are twice as likely to contract HIV compared to their male counterparts. In some cases, it is due to congenital HIV, the pressure to consume opioids or rape. Moreover, women face treatment barriers; many public services are limited to married women while single women are unable to access treatment at all, reflecting the existence of gender inequality based on women’s civil status. A study of young girls from 18-24 years old in Soweto, South-Africa showed that even if these women knew where to find proper treatment, they did not go because of the unsupportive attitudes coming from their community, parents and health experts. Clearly, the growing drug trade has a significant impact on gender imbalances, further reaffirming the injustices and affecting women’s survival rate due to inaccessibility to treatment.

In sum, to redress the consequences of drug trafficking in East Africa, some suggestions should be considered. First, there is a need for more government accountability. The people have to be able to trust their government. To do this, national governments should collaborate with regional leaders to defeat local drug networks. Additionally, since drug trafficking networks have recently adopted a horizontally structured organization to work undetected, anti-narcotics programmes should reflect the changes and adapt to the fast-pace exchanges of the illicit business. Second, because many medical practitioners are not properly trained to deal with drug addiction and to administer proper rehabilitation, the quality of healthcare supply remains relatively low. Governments should not only invest more strategically within the healthcare system, but also in the education system. Finally, due to recent findings on methadone’s efficacy treating addiction, all countries should promote, bring awareness to, and normalize the programme. Overall, a successful minimization of negative externalities associated with drug trafficking and abuse can only be achieved by first improving the social and political institutions which are defective and responsible for the rise of corruption on the continent. Following the successful implementation of anti-corruption programmes, the government and society can address cultural issues such as stigmatization and the status of women through awareness campaigns.

Edited by Alexandra Yiannoutsos