Can We Be Against the Pipeline and For the Liberals?

The Canadian Arctic is thawing 70 years earlier than predicted, and the country is warming at twice the global rate. Himalayan glaciers are melting rapidly; sled dogs are sloshing through increasing amounts of seawater in Greenland; an island in Louisiana is sinking, causing locals to evacuate. The UN warns that a climate-related disaster is happening once a week. Meanwhile, Canada’s political scene is giving mixed signals with regards to whether climate action is a priority or not.

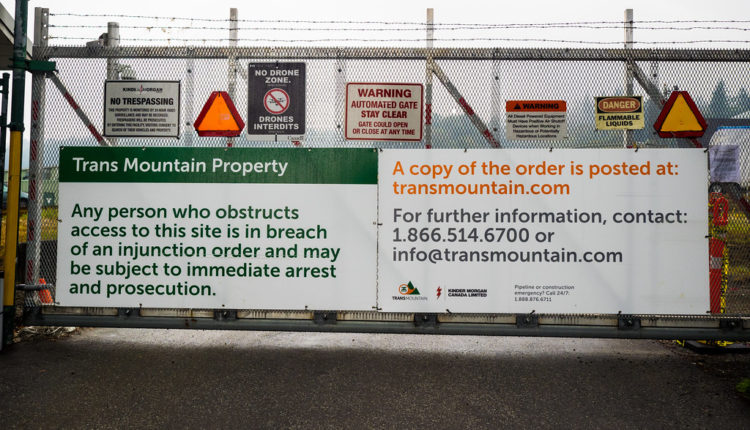

On June 17th, the Canadian House of Commons voted to affirm that yes, we are in a national climate emergency. It passed 186 to 63. Just a week prior, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that by 2021 there will be a ban on single-use plastics. And, of course, Trudeau also announced just days earlier that the highly controversial Trans Mountain pipeline had been approved. The pipeline lies at the intersection of so many of Canada’s most pressing issues: oil, jobs, the climate crisis, and Indigenous rights to land. The case presents a blunt picture of the country’s priorities. Despite resistance from multiple indigenous activist groups and legitimate legal claims to sovereignty, the state has proven its willingness to continue to claim plots of land for its own purposes.

The idiom “you can’t have your cake and eat it too” is all too pertinent. With the federal election coming this fall, Trudeau is trying to pander to both sides: we can ban plastics and simultaneously build pipelines. He wants to please both the voters who prioritize the climate and those who prioritize immediate economic development via the pipeline. He is trying to take a middle way. But will voters from both sides buy into this middle way, or will the politics of compromise force voters to turn their backs on him?

Steven Guilbeault, a prominent Quebec environmentalist, made headlines when he decided to run as a Liberal MP this fall, despite the fact that he is against the Trans Mountain pipeline. He said that he is afraid the Conservatives will win in the fall, and that if they do, the country would risk all the progress it has made so far with the Liberals on climate policy. And what exactly is that progress?

Bills C-48 and C-69, which passed June 20th, are the most recent advances. C-48 bans oil tankers from traversing the waters in northern British Columbia, and C-69 outlines an overhaul of the National Energy Board and the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency. Neither satisfies the NDP or the Conservatives, but that could just be because the Liberals are running their typical centrist course. Premier Jason Kenney of Alberta has said that he will challenge both bills in court. He argues that C-48 is an unfair attack on Alberta, given that its oil is overwhelmingly exported through the Pacific, yet oil tankers pass freely in the Bay of Fundy and through the St Lawrence. Kenney called it “an unconstitutional violation of Canada’s economic union” and has also dubbed C-69 the “pipeline killer,” suggesting that the increased amounts of red tape will seriously inhibit further oil development. Others note that C-69 does not amount to much, because it merely restores a few regulations that Stephen Harper’s government removed in 2012. Although the policies are headed in the right direction, they do not match the urgency of the climate crisis.

The theme of taking the federal government to court over environmental legislation is not new. Trudeau’s carbon tax has met serious resistance from several premiers. Saskatchewan’s Court of Appeal recently issued a 3-2 opinion that the tax is constitutional, though the case has since been ushered forth to the Canadian Supreme Court, where it is expected to be heard this December. Even if the Supreme Court sides with the government, the tax will not accomplish everything that environmentalists want from it. Nonetheless, what should have been seen as a mediocre but ultimately good piece of climate legislation has become politicized by media outlets, such that many Canadians do not know that the legislation would actually put more money in their pockets. The Liberals may have won legally thus far in the carbon tax process, but they have not won politically.

And what lasting power will any climate plan have if it does not benefit from broad political support? Trudeau has not done very well in terms of communicating his climate crisis plan, but that may just be because it is a hard pill to swallow, no matter who is doling it out. Sandy Garossino argues in the National Observer that if Trudeau had not accepted Trans Mountain, he would have been voted out just like Kathleen Wynne and Rachel Notley (until recently the Premiers of Ontario and Alberta). Garossino suggests that Canadians need to view the pipeline as part of a long-term political and economic plan. Because, if we lose Trudeau in the fall, we would also lose any climate plan whatsoever. Scheer has made clear that he is not only against any kind of taxing, but he also plans to scrap all fuel standards. According to Scheer, yet-to-be-discovered green technology will save the day. The country should not place their bets on this dream.

Kathryn Harrison wrote a response to Garossino’s op-ed, suggesting that complacency in the face of a global disaster should not be our standard. She writes: “But let’s take a step back and consider what’s being proposed: funding a transition away from oil by expanding oil production. That makes as much sense as eating more cake to build up strength to go on a diet.” It is a refreshingly logical attack, except that not all addictions or habits need to be broken cold turkey. While scientists, activists and journalists must continue to do their best to compel citizens that a more aggressive climate crisis plan is necessary, we should not simultaneously lose sight of what the country is politically ready for in a given moment. It is crucial that protests on climate change and on Trans Mountain specifically should continue. But a moderate political strategy might be necessary in order to not lose the battle altogether.

It’s worth asking what makes a country “politically ready” for radical change. Within the American context, Ocasio-Cortez changed the conversation on climate action unbelievably quickly by branding the Green New Deal. Whether the Green New Deal in her iteration is accepted or not is beside the point that Democratic candidates now consider it as a reasonable policy plan. Kamala Harris has endorsed the Green New Deal, and most other candidates have as well, in some capacity. But the other side of the coin is that as Democratic candidates rush to find the pulse on climate action among the Democratic Party, they are at risk of shooting themselves in the foot by becoming unelectable to the general populace. We’ll watch as they compete to reassure progressive voters now, while whoever wins the nomination will switch to more moderate rhetoric to win over Trump voters.

So can we be against the pipeline but for the Liberals? I think we have to be.

Guilbeault, the Quebec environmentalist who is walking this tightrope, has been labelled an “environmental turn coat or sellout.” Fellow environmentalists and activists are disappointed and point to his decision to run as MP as absurd. Maybe they are right. But what if he is?

Guilbeault suggests that climate policy is actually quite similar across the Liberals, NDP and the Greens. As for the differences between the parties, he cites the pipeline, and the fact that “the Liberals have actually had to run a government for the past four years.” He’s embarked on a thorny, deeply political challenge of fighting within a party that he has fought against for most of his life, attempting to steer the party towards further climate action from within.

It’s odd how the word compromise holds two connotations. On one hand, compromise is seen as a virtue. If one is able to compromise, one makes concessions, but at best in a level-headed way such that some expedient solution is found that remains satisfactory to both parties. On the other hand, “to be compromised” is never considered to be a good thing. Certain moral visions are only worthwhile if they are taken at full throttle, because any concessions lead to an immeasurable loss. Canada, like the United States, is increasingly divided with regards to its priorities. At the risk of handing the torch to Scheer, who would scrap all middle-way plans for climate action, it seems increasingly politically necessary to make an icon out of Guilbeault and his willingness to compromise. The middle way never feels quite right, but maybe it’s the best out of a lot of bad options.

Edited by Koji Shiromoto