Undersea Espionage: Who Owns Underwater Internet Cables?

Via: Pixabay, chaitawat

Via: Pixabay, chaitawat

Deep below the sea rest the veins of modern life: internet cables. Over 750 miles of undersea cables anchored to the sea floor connect the world. These cables cross seas and oceans, traversing international waters and national boundaries. But in this era, more so than any other, knowledge is power. Ultimately, those who own these cables will be able to control and monitor the information that passes through them. Not bound to any one territory, who has the right to control these cables?

Digital Gold

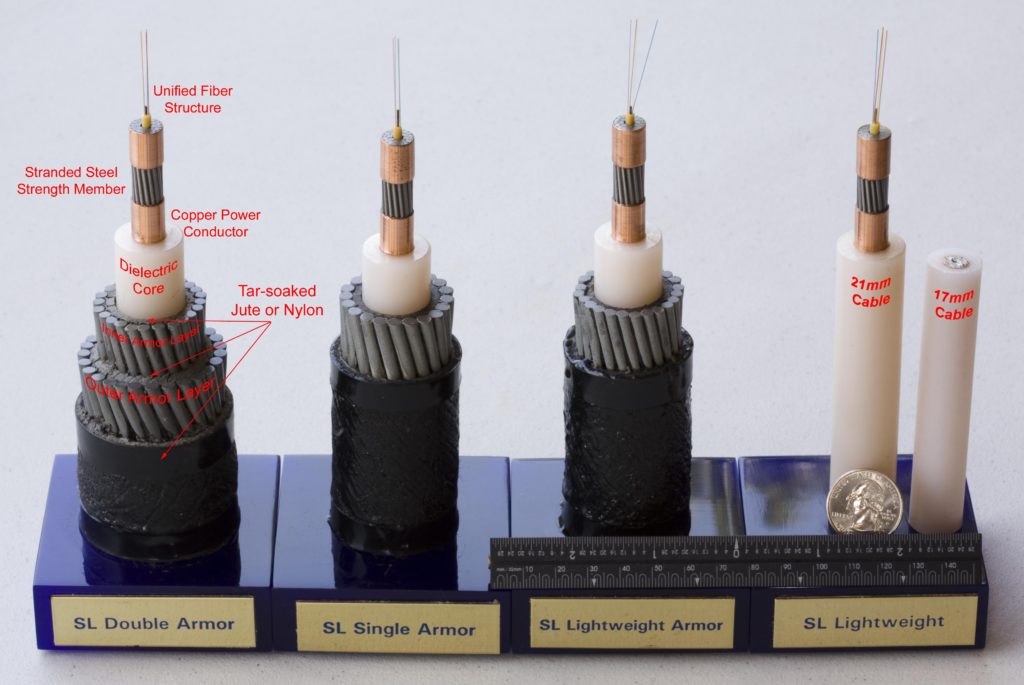

Internet cables are protected as though they contain gold, and to some extent, they do. Over 95% of precious data flows through those fibres every day—including government correspondence, user profiles, and banking information. Not only are they routinely inspected for external damage from dropped anchors, earthquakes, or even shark bites, but they are also patrolled by their owners to deter any information tapping from foreign governments.

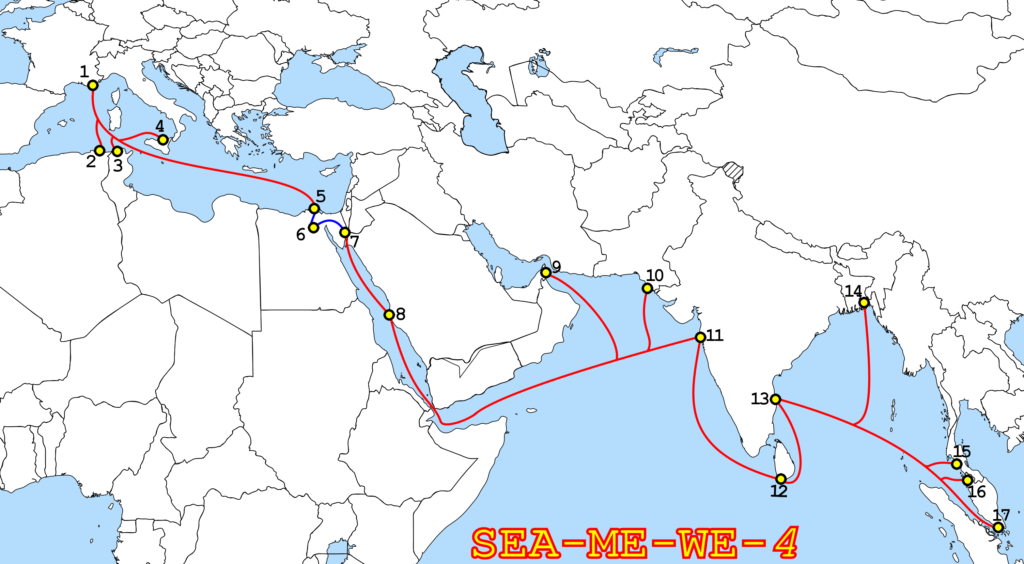

All this is done through the collaboration of private investors, tech companies, and governments. Projects are backed by governments or state-owned companies, and resources are poured into the process of laying down the cables; hundreds of millions of dollars and the most advanced tools and materials all dedicated to building the backbone of the modern world. The operation takes years; authorities need to map the safest route, damage-proof the cables, dig the trenches, and lay down the cables. All this investment is worth it, for they will give access to information abroad and the potential to control the flow of data.

A key for espionage

Tapping undersea cables for espionage is not a new idea. Back in the 1970s, submarines were sent on missions like Operation Ivy Bells. Troops were sent down to the bottom of the Sea of Okhotsk in Soviet territorial waters to find a five-inch diameter cable that carried communications between military bases. They installed a 20-foot long listening device on the cable to record Soviet messages. The tap was eventually discovered, and that specific mission had been compromised.

Such operations could still be ongoing beneath the ocean without us knowing. However, with tech giants quickly gaining control of more and more cables, there could be a new way to spy on other countries. Partnerships or deals with these companies can easily give governments access to the information that flows through the cables, giving Facebook and Google even more leverage than they already have. With state backing and investment, tech giants could control and sell more information, and they could even persuade governments since they own the cables that deliver their secrets. For example, Google could restrict access to information vital for national security interests if governments refuse to give them more tax exemptions.

Cable Ownership

These cables run through international territory, muddying the question of ownership. It begs the question: are sections of these cables subject to the local laws of the territories they cross?

Private companies will argue that they’re private property and thus subject to solely the company’s control. However, they still must comply with international laws and treaties regarding marine territory. According to Article 87 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), states have the freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines in international waters, and only areas that cross into sovereign territory (the Exclusive Economic Zone [EEZ] or continental shelf) are subject to restrictions. Article 112 stipulates that the freedom to lay down cables must be subject to the rights of other states to do the same. Once in the sovereign state’s territorial sea (12 nautical miles from the coast), companies who piloted the project are required to possess various permits, licenses, and environmental agreements according to local laws and international treaties before operating within the country.

While ownership of the cables themselves vary from company to company (state-owned or private), tech giants like Facebook and Google are quickly taking over the seas. By 2020, both companies will own about 29% of the cables that run throughout the world; they even own a couple of whole cables from end-to-end. For instance, Google currently owns the entirety of the Curie cable, which runs from Chile to Los Angeles.

With tech giants taking over, international and local laws need to be updated to ensure that the sovereignty of the different states the cables cross is protected. It’s a unique position they currently occupy: the cables are privately-owned but are allowed to traverse sovereign territory. States are subject to the international treaties they signed, but private companies’ hands are not as bound. UNCLOS awards states the right to lay down internet cables, and this extends to their residents. However, since cable ownership cannot be determined easily by flying a flag, it’s difficult to hold a single company accountable. While they still need permits to lay down the cables, the information they collect can be considered property of the owner. This gives private companies significant leverage over governments. If current regulations are not updated, tech companies have the potential to gain a monopoly over our data, and governments may find it more and more difficult to control their behaviour.

China and the South China Sea

All this considered, China’s presence in the South China Sea is even more intimidating. As they continue to take control over the various islands in the area, they will be able to lay down their own network cables away from the eyes of the international community. Their goals to expand their 5G networks, headed by Huawei, will give the Chinese government even more control over the information that flows into and out of the country. The infamous Great Firewall can be expanded and improved further if the state has complete control over the internet cables that source internet traffic. Tapping the cables will no longer be necessary for espionage if the state owns the whole thing.

The Huawei Marine Networks has already begun to lay down 100 submarine cables across the world, and it completed a 4,000-mile cable last year that runs from Brazil to Cameroon. China Unicom, the company that owns the cable, was able to win the bidding because of the subsidies they received from the government. Possession of the South China Sea could mean the control over the data that flows between surrounding countries. A monopoly on the network can give China the intelligence and leverage necessary to control such regions.

China, however, is simply taking a page from American books. Former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden revealed PRISM to the public: a program wherein the U.S. government collected user data from various internet companies, and they could do so without a warrant. Global superpowers know that intelligence is the key to control, so they have been working with telecommunication companies for years, whether it be through under-the-table deals or direct partnerships. The danger with China’s case, however, is the way they are attempting to circumvent international regulations and norms. By annexing islands in the South China Sea, they can claim that it is within their sovereign territory. Therefore, international bodies cannot interfere with their desire to lay down new internet cables. They would technically be operating within their rights even though their operations would affect all of the Southeast Asian countries. Huawei’s 5G networks would spread across the region, so it will be more and more difficult to use non-Chinese servers. Accompanied by its economic influence over the area, China will reinforce its position as hegemon of the continent with their increasing control over data. Violations of international regulations and norms—flooding the market, environmentally damaging practices, and manipulation of their currency—will become harder to sanction, especially if the Chinese have enough dirt on other nations.

Protecting Our Data

Individual consumers of the internet may not have the power to fight this control themselves. There are only a few companies that own the cables, so there aren’t many choices if one needs to use the internet. These issues need to be brought up again in order to update the international conventions of the sea. UNCLOS may protect states’ rights to lay down the cables and their sovereignty once a foreign wire is in their territory, but specific agreements on how private companies should behave are yet to be clarified. Tech giants and government-backed data businesses are gaining more and more control over the internet, so they need pressure from other states to keep them in check. Information is precious to us all, so we ought to take steps to protect it, whether it be from foreign government control or a shark lying in wait.

Edited by Shirley Wang and Christopher Ciafro