The ~ Anglophone’s ~ Guide to the Bloc Québécois

The Bloc Québécois. Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bloc_Qu%C3%A9b%C3%A9cois-logo.svg

The Bloc Québécois. Photo credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bloc_Qu%C3%A9b%C3%A9cois-logo.svg

In the last few weeks, the MIR has been covering the federal elections in order to keep McGill students informed and ready to vote on the 21st. Bringing to you numerous interviews, podcasts, event reports, we try to cover as wide a range of issues as possible, attempting as much as possible to provide all the information both in French and in English.

This article, coming late in the campaign, aims to explain a phenomenon that we have not covered yet: the Bloc Québécois (BQ). For students new to Québec, the mere existence of such a political party may seem odd.

“You’re telling me that they run at the federal level, elected to Ottawa, but solely running for ridings in Québec, with no chance of forming the government at the end of the elections?”

Yes. Exactly.

Although it is not uncommon in places with strong independentist movements — think Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, SNP in Scotland — I understand how perplexing this fairly recent political entity can seem. From the admittedly biased point of view of a Québécois student, I will attempt to explain the historical particularities of the province that made the existence of this party so necessary at the moment of its foundation by Lucien Bouchard in 1991.

Despite strong provincial pride in many provinces, especially in Alberta, regional “Blocs” are essentially non-existent outside of Quebec. The unicity and sheer existence of the BQ is deeply rooted in the perennial Canadian Franco-Anglo divide, the so-called “two solitudes”, incorporating cultural, historical, religious and linguistic divides. Let’s quickly rewind through our captivating history in order to understand where this divide comes from and therefore attempt to explain the existence of the BQ.

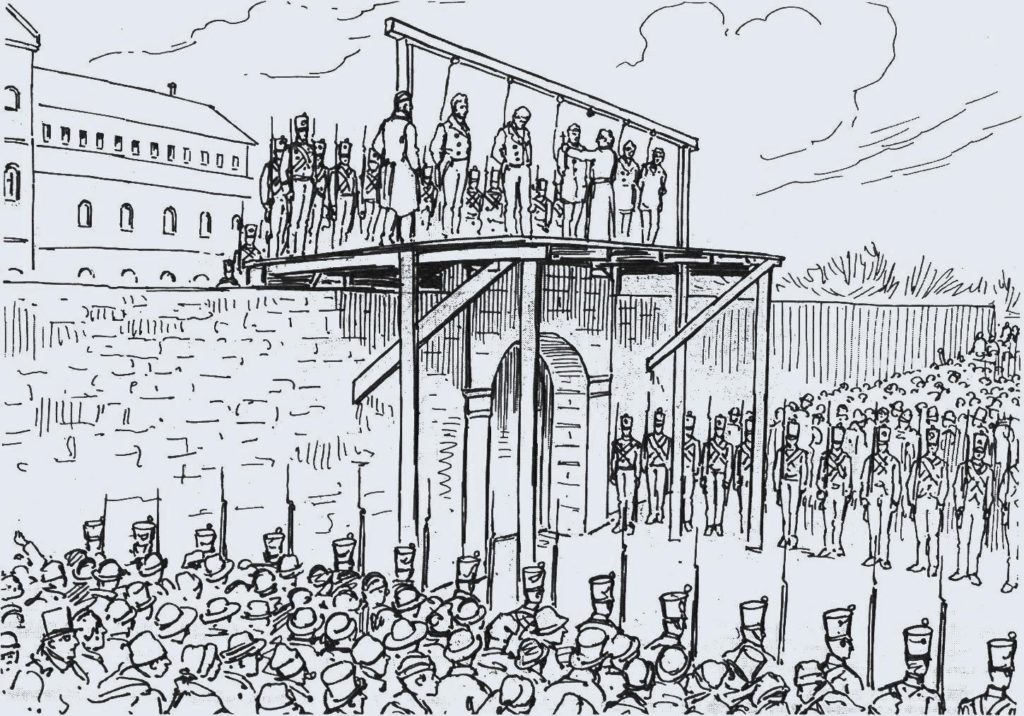

After the conclusion of the Seven Year War in 1763 and the cession of practically all French North American territories to England, several attempts were made to assimilate Catholic French speakers. The accumulating pressure exploded in its most infamous form in the 1837-1838 Rebellion of the Patriots, leading to the hanging of 12 French-Canadians. In light of these tensions, the 1839 Durham Report suggested that the assimilation of a people “without history and literature” — i.e. the French Canadians —would end hostilities between the two groups.

This “acultural” and “ahistorical” people nonetheless kept thriving: the Province of Québec was one of the four founding provinces of the 1867 Confederation and fought for the Dominion in both World Wars — perhaps sometimes reluctantly, but Québécois still sacrificed their lives massively in events such as Ypres and Dieppe. And yet, tensions kept accumulating: the 1955 Richard riots, for example, were symptomatic of these latent emotions ready to outburst at any trigger. The October Crisis and the establishment of martial law in Montréal deepened the distrust Québécois people felt towards the federal government, setting the table for the apex of the increasingly strong nationalist movement in the 80s and 90s.

In 1980, the first referendum for independence failed by a large margin (60-40). In 1982, the patriation and signing of the Constitution, under the leadership of Pierre Trudeau, was meant to be a unifying moment for Canada. Rather, the infamous “Night of the Long Knives,” where Trudeau and the 9 other Premiers signed the constitution without René Lévesque and the Province of Québec, further marginalized the Québécois people, and fostered their continued unrest.

The 1984 elections were a strong testament to this feeling: in 1980, Trudeau’s Liberals had won 74 out of 75 seats disputed in Quebec in the federal elections. In 1984, Mulroney’s Conservatives shockingly won 58 of those 75 seats. The Conservative leader’s mandate was stricken by a series of constitutional crises, culminating in the failure of the Lake Meech Accord. Following Quebec’s demands to be recognized as a “distinct society,” Mulroney put in place a series of measures that effectively granted some special privileges to the province of Québec. All provinces needed to ratify the Accord in their own Parliaments, which did not succeed, namely because of voices such as the one of Elijah Harper, who should be underlined and praised for his arguing that Indigenous Peoples, who also sought special privileges, had not been consulted during the process.

The failure of the Lake Meech Accord in 1990 led to another round of constitutional crises: the 1992 Charlottetown Accord once again recognizing Québec as a “distinct society” did not pass the test of a nationwide referendum. Québec nationalist sentiment was at its peak. It is in this context that the Bloc was founded in 1991. Gilles Duceppe was the first to be elected for the Bloc, although not officially, as his by-election in 1990 pre-dated the official recognition of the BQ as a federal party — he ran as an independent.

After the Lake Meech and Charlottetown constitutional fiasco, however, Mulroney’s popularity in Quebec unequivocally waned. In the party’s first federal elections in 1993, the Bloc Québécois elected 54 candidates to the House of Commons, forming the official opposition in Ottawa with the second most elected MPs after the elected government. Nationalist sentiment culminated with the narrow-loss — or victory, depending on your perspective — of the 1995 Québec referendum for independence (50.6% No to 49.4% Yes). No referendum has taken place since and support to independence has slowly weakened.

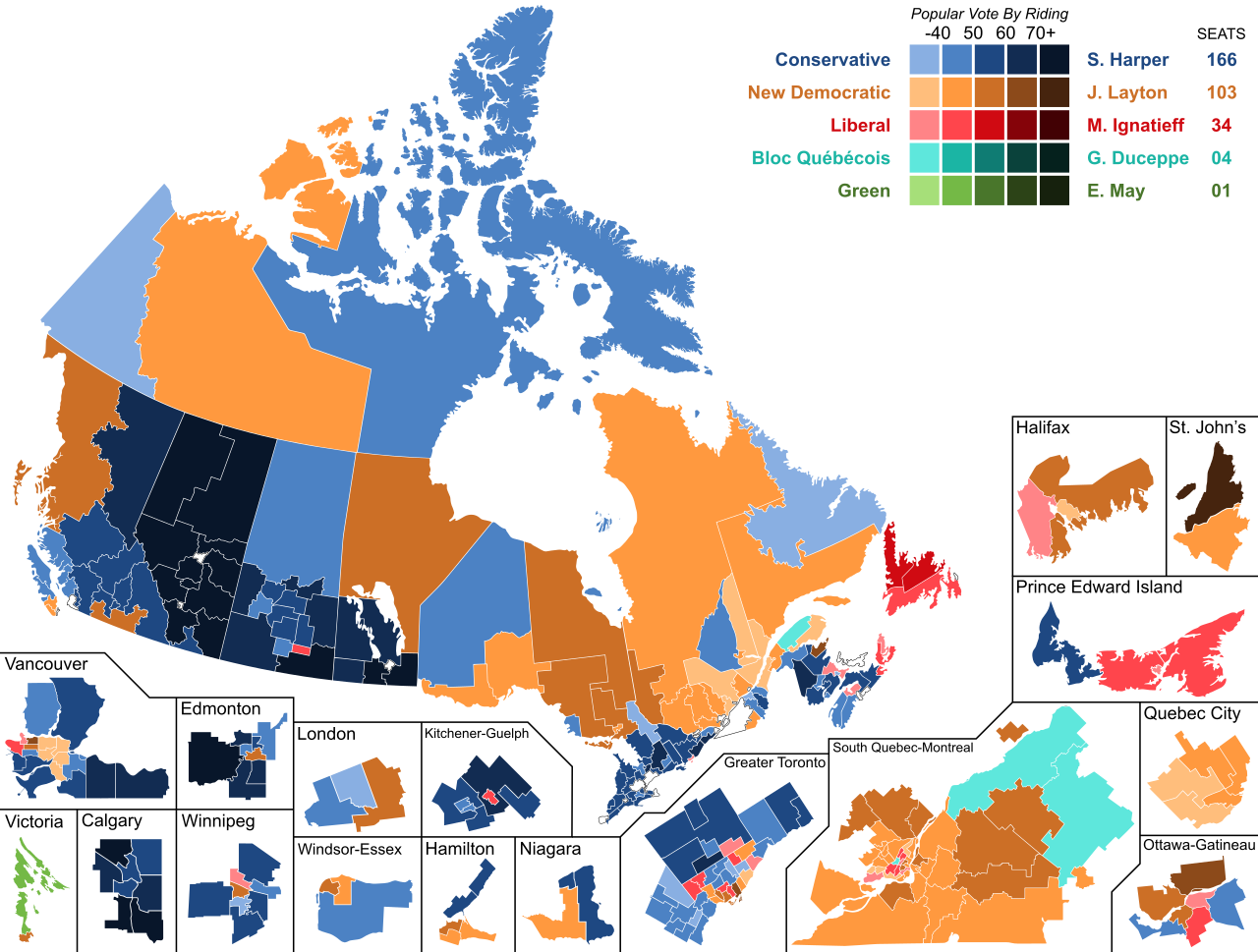

Yet the BQ remained and continued to claim a strong presence in the House of Commons. Considering the circumstances surrounding its genesis, its objectives are quite clear: to represent the interests of Québécois people in Ottawa, since no other party has been deemed up to the task. The consistent popularity of the BQ in Québec has made the quest for a majority in Parliament an arduous task for other federal parties: minority governments were formed under Paul Martin in 2004 and under Stephen Harper in 2006 and 2008. During the Harper years, the Québec electorate seemed satisfied with this arrangement; they saw it as if they were either preventing a Conservative government from attaining the majority or at least keeping the balance of power in Québec hands.

This was the case, until 2011. The province became enamoured with the highly charismatic Jack Layton of the NDP, leading to the “orange wave”. From holding a majority of Québec seats since 1993, the BQ crashed to 4 elected MPs, losing official party status. The running gag at the time was that the whole Bloc caucus would thereafter be able to carpool together to Ottawa. The 2015 elections saw the BQ fail, yet again, to regain party status, with only 10 elected MPs. With the free fall of the NDP, the Québec electorate chose in 2015 to “be part of the government” instead of being confined to the opposition, something that had not happened since the Mulroney era.

After two successive stinging defeats and chaotic leadership races, many thought that the end of the BQ had come. After all, as Jagmeet Singh eloquently assessed in the last French leaders’ debate, the Bloc Québécois does not hold a monopoly over Québécois people’s interests. Considering the volatile support for the NDP and the Liberals in the last two elections, it seems that the Québec electorate largely agrees.

And yet, we are currently witnessing a resurgence of the BQ, with 338 Canada projecting that the Bloc may win over 30 seats. Considering the fact that the current Prime Minister is Québécois and that the majority of Québec seats are currently Liberal, as well as bearing in mind that support for Québec independence has not significantly risen, this resurgence a priori can seem quite surprising. How can we explain it? It is still too early for us to fully assess, but the strong showing of leader Yves-François Blanchet in every debate — even in English — must have played a non-negligible role.

Furthermore, I believe that the recent political situation has played a significant role in the BQ’s upswing. The election of the CAQ in 2018 was the symptom of an increasing nationalistic sentiment — leaning much more towards identity nationalism than an independence one. This sentiment has transpired with the recent reforms on immigration (Bill 9) and the fiercely debated Bill 21 on secularism. On several occasions, Blanchet explained that 70% of Québec voters were for this law and that unlike Trudeau, he would not attempt to rebuke it from a federal standpoint.

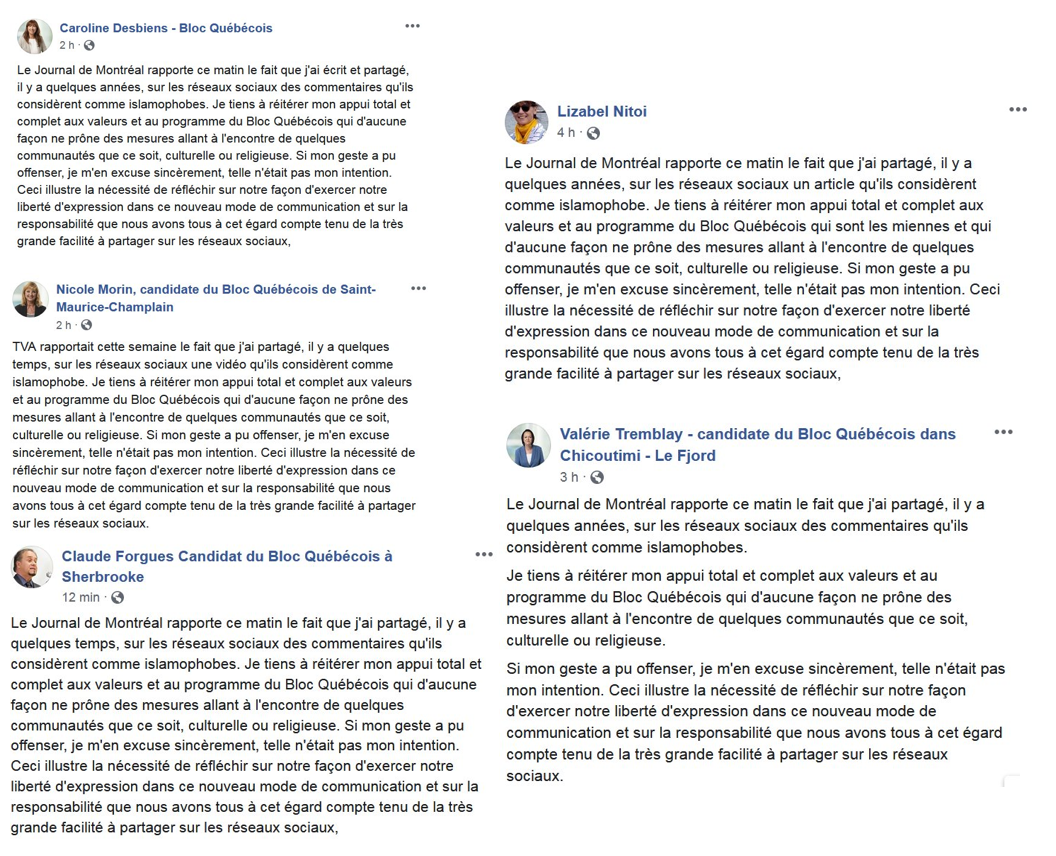

However, five candidates from the BQ were recently called out for previous islamophobic statements on social media. The response from their leader and the party was, in my opinion, insufficient. A controversy arose in the last weeks when the Bloc released a slogan including the catchphrase “votez pour des hommes ou des femmes qui vous ressemblent”, which was translated in the Anglo world as “vote for candidates who look like you”. In the English debate, Blanchet appropriately stressed how dishonest this was, as “ressembler” did not necessarily mean the physical connotation entailed by “look” but could rather refer to values or ideologies, etc. He underlined that Ignatieff, in 2011 and Mulcair, in 2015, had both used this formulation as well. His argument was convincing, but somewhat irrelevant: the mere fact that people interpreted in this specific way, unlike for Ignatieff or Mulcair, was symptomatic of the vision people have of his party.

The interests of many underrepresented or ostracized groups ought to be put forward in Ottawa, namely Indigenous peoples. Nonetheless, Québec interests are not mutually exclusive with those of these groups and considering the unique historical and cultural context that has been laid out in this article, as well as the sheer demographic size of the province, the interests of the Québécois people should definitely be vehemently represented in the House of Commons. But the question in the minds of many still remains: is the Bloc Québécois really the best party for this crucial endeavour?

Edited by Alec Regino and Allegra Mendelson