“Tout le Monde Reste en Silence”: Human Rights Violations in Vietnam

Nguyen Van Hoa, seven years. Phan Kim Khanh, six years. Tran Thu Nga, nine years. Nguyen Van Duc Do, eleven years. Duong Thi Lanh, eight years. Tran Thi Xuan, nine years.

These are the names and the sentences of six Vietnamese prisoners of conscience; individuals who were imprisoned due to their political and religious beliefs. They were convicted due to their involvement in alleged “propaganda against the state” — an offence interpreted as any form of dissent towards the State and the government — through their online blogging and public rebukes of the current administration in Vietnam.

Vietnam is globally reputed for its systematic censorship and severe punishments towards dissidents. In fact, Vietnam was ranked 176th in Reporters Without Borders’ freedom barometres, placing it in the “dangerous” category. The Vietnamese government has enacted multiple repressive measures, including cyber unit Force 47 , a military cyber warfare unit meant to crack down on “wrong views” on social media. This repression is further strengthened by a law that went into effect this year, which requires service providers to remove any “offending content” if requested by the Ministry of Public Security or the Ministry of Information and Communications. Human Rights Watch reports that any form of dissent towards the government can be met with arbitrary imprisonment, surveillance, house arrest, travel bans, interrogation, harassment, and even violence. The organization, along with many scholars such as Dr. Nguyen Manh Hung, report that dissidents even face violence from “unknown men in civilian clothes” who are given impunity.

Like many countries that restrict freedom of expression, the Vietnamese government has justified their treatment of dissent through their constitution and penal code, reflecting a clear lack of constitutional accountability for Vietnamese government. This is best exemplified through Article 11 of the Constitution, where dissent is depicted as a threat to the wellbeing of the state:

1. The Vietnamese Fatherland is sacred and inviolable.

2. All acts against the independence, sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity against the course of building and defence of the Fatherland, must be strictly punished.

Likewise, articles 79, 88, and 259 are often invoked by the government to convict bloggers and political dissidents.

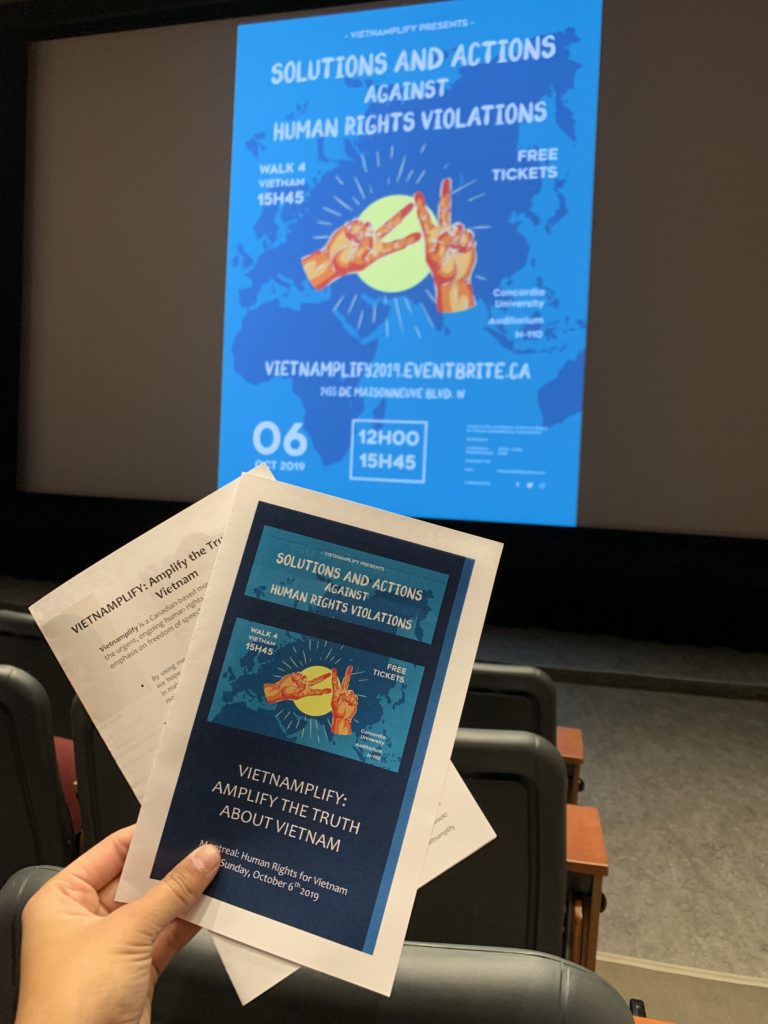

In the midst of such injustices arise activism and calls for democracy that extend beyond the government’s control. On Sunday, October 6th, the MIR had the privilege of observing such a movement in Montreal, thousands of miles away from Vietnam. Vietnamplify, a Canadian-based organization, works to “expose the urgent, ongoing human rights violations in Vietnam” through conferences and marches that aim to raise awareness and encourage constructive action. Earlier this month they held a conference to discuss current issues within Vietnam and ways in which the Vietnamese-Canadian community can respond.

Dr. Khue-Tu Nguyen, the President of Canadian Youth for Human Rights in Vietnam, spoke about needed action at the micro- and macro-level to redress human rights violations by the Vietnamese government. She encouraged attendees to spread awareness, join/create advocacy groups in their community, or support programs such as “adopt a prisoner.” The aforementioned program is an initiative wherein Canadian locals can ask their Member of Parliament (MP) to “adopt” a prisoner of conscience. If the MP agrees, they will receive a fact file about the prisoner and will be updated about their lives in prison. If a prisoner is harmed or treated poorly, the MP will then write a letter to the Vietnamese government. This would serve as a form of demonstrable and tangible Canadian commitment to advancing government accountability in Vietnam. It is also the principle that rests at the heart of Vietnamplify’s macro-level solutions and mission: “We believe that Canada is influential enough to put pressure on the Vietnamese government to respect the basic rights of their citizens.”

But why is there a need for international pressure? And what role can countries like Canada play in addressing human rights violations in Vietnam?

In order to answer these questions, it is imperative that we delve further into the complexities of this issue. At a superficial level, the reasons behind the Vietnamese government’s implementation of such laws may be obvious: to consolidate power by eliminating all potential backlash. However, it’s crucial to ask why a government would need to invoke such measures to protect their authority in the first place.

In the 1980 and 1993 constitutions, the Vietnamese Communist Party officially became the only political leadership, becoming the most powerful institution in Vietnam. Since the current government is assured that they will not be challenged by another party, it may seem as though there is no threat to their authority. However, Dr. Nguyen Manh Hung reports that tense relationships with China remain a threat to Vietnam’s sovereign identity.

Vietnam is one of the countries laying claims to Spratly Island, one of the disputed islands in the South China Sea. According to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), all territory which extends up to 200 nautical miles from a country’s baselines are considered a part of its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The Convention states that countries have “sovereign rights” to the natural resources—which happen to be economically significant—within their EEZ. Every country within this region, including Vietnam, uses UNCLOS to stake claims to areas within the South China Sea, with the exception of China, who claims sovereignty over the entirety of the region using the “9 Dash Line” — a demarcation they drew. However since the 9 Dash Line is inconsistent with the international maritime legal framework, China began the construction of man-made, militarized islands to solidify their claims to the Spratly Islands. Analysts, such as those at Vox, interpret this as a willingness to use military measures to protect these islands. They predict that this will intensify contention among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, potentially leading to conflict.

If Vietnam is under geopolitical pressure which could potentially manifest into armed conflict, ensuing internal instability has a number of implications for the Vietnamese government. Dr. Hung reports that many political dissidents in Vietnam oppose the political structure of the country or the Communist regime. If such sentiments accrue into nation-wide protests, the government risks losing their authority altogether, including authority tied to their claims over the Spratly Islands, among other maritime claims. With this geopolitical context looming over the government, its harsh response to any dissent can be explained as an attempt to consolidate internal affairs.

Tense diplomatic relations and economic hardships give experts reason to believe that Vietnam is in need of international alliances. Dr. Hung argued that such conditions have encouraged Vietnam’s new “multilateralization and diversification” of international trade policies, despite being a communist regime. For example, Vietnam’s relationship with Canada was significantly strengthened in 2017-2018 and is expected to grow. This is exemplified, as “two-way merchandise trade between Canada and Vietnam reached $6.2 billion” in 2017, a 1.1 billion dollar increase from 2016.

This is why activists believe international pressure is the main solution. Because of the national debt accumulation in Vietnam, trade pressure, in particular, is where Canada can play a transformative role in pushing Vietnam to address their internal human rights issues. The Canadian government reports that “Vietnam has been Canada’s largest trading partner in the ASEAN region since 2015.” Since Canada is both an investor in Vietnam’s development and a prominent trading partner, there is an economic incentive for Vietnam to maintain positive relations. Therefore, should the Canadian government, along with other prominent trading countries, place conditions on current agreements or funding there will be a greater chance at reform. Moreover, positive relations with the international community will only bolster Vietnam’s case for territorial claims in the South China Sea.

Activists at the conference advocated for international pressure, citing the success of the case of “Mother Mushroom,” the pen name of Vietnamese activist Nguyen Ngoc Nhu Quynh, who was convicted of spreading “propaganda.” After a video of her being mistreated by the Vietnamese government went viral, there were international calls for justice for Mother Mushroom. Shortly thereafter, the U.S. embassy in Hanoi requested her release and in 2018, Quynh received refugee status in the U.S. The case of Mother Mushroom is one that exemplifies the power of global awareness and international pressure. It is for this reason that activists at Vietnamplify and all over the world continue protesting and creating awareness for their cause. It is in hopes that awareness and international pressure will manifest into large-scale constructive action.

The feature image of this article was taken by Hayah Amin at the march after the Vietnamplify conference. We thank their organization for allowing us to participate.