The Unsurprising Nature of U.S. Withdrawal from Syria

Image taken from Akçakale during the bombing of Tel Abyad, 2019.

By Orhan Erkılıç -https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83056389

Image taken from Akçakale during the bombing of Tel Abyad, 2019.

By Orhan Erkılıç -https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=83056389

The recent decision by the United States to pull out of Syria and allow for a Turkish intervention is a major foreign policy shift that has drawn sharp responses both domestically and abroad. From Democrats to Republicans, it seems Congress has achieved a rare moment of bipartisanship in their mutual concerns with the decision. In the eyes of many, the Kurds have been betrayed and left for dead.

The Kurds are an ethnic minority living primarily in Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq. During the Syrian Civil War, the Kurds in Syria (concentrated in the north of Syria, along the Turkish border) were able to assert some degree of autonomy within the northern area known as Rojava and organized themselves as a key force in fighting off ISIS. The United States forged an alliance with the Kurds and supplied Kurdish forces with military equipment, training, and logistical support to help them in the fight against the Islamic State. Because of these ties between the US and the Kurds, the recent decision to pull out, ultimately allowing for Turkey to invade the region, has been met with harsh criticism from nearly all major stakeholders.

Turkey’s involvement is far from unexpected given their historical animosity towards the Kurds, and given their opposition to a Kurdish homeland on their border. Turkey has fought restive Kurdish groups domestically for decades and fears that a Kurdish state would further embolden the ambitions of Kurds inside Turkey’s borders. While this is unquestionably a case of abandoning American allies in their time of need, it is unsurprising given past American foreign policy decisions. While a number of examples exist, there are a few which are particularly salient and relevant.

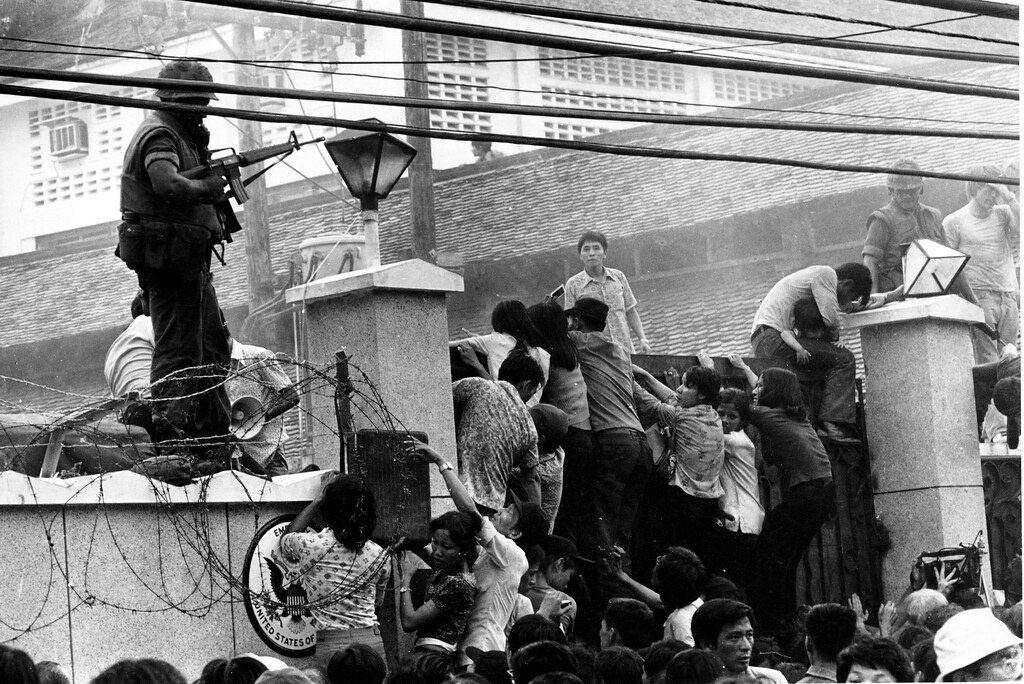

Of all the cases, the most relevant would be the Vietnam War, where the US supported South Vietnamese forces in their fight against the Soviet-aligned North Vietnam. But as the war dragged on with mounting American casualties, domestic opposition, and no end in sight, the Nixon administration eventually decided to repatriate US troops, thereby ending their involvement in the conflict. To ensure the viability of South Vietnam post-withdrawal, the US implemented a series of measures to bolster its ally’s capacity. Through operations such as Operations Enhance and Enhance Plus in 1972, the Americans supplied weapon systems to South Vietnam as a means of ensuring its defense without a US presence. President Nixon also promised South Vietnamese leader Nguyễn Văn Thiệu that America would defend them from the North with airpower. Thiệu would later re-state this promise when he told President Gerald Ford in a letter in 1975: “Hanoi’s intention to use the Paris agreement for a military take over of South Vietnam was well-known to us at the very time of negotiating the Paris Agreement…Firm pledges were then given to us that the United States will retaliate swiftly and vigorously to any violation of the agreement…We consider those pledges the most important guarantees of the Paris Agreement; those pledges have now become the most crucial ones to our survival.”

However, this promise was quickly broken. Once the North attacked the South during the 1975 Spring Offensive, the US refused to intervene and South Vietnam fell soon after. This example of American betrayal bears certain similarities to the situation regarding the Kurds in Syria. In both, the groups had been supported both logistically and militarily by the United States, in prolonged wars, and both the Kurds and South Vietnamese were praised as essential allies to the United States. Despite this, both were eventually abandoned, at penultimate moments, to the mercy of other powers.

In addition to Vietnam, Iraq provides two other particularly relevant case studies. The first case is the end of the First Gulf War in February 1991, when the American government encouraged the 1991 Uprisings by producing and airing numerous radio broadcasts in support of resistance against Saddam Hussein. President George Bush called for “the Iraqi military and the Iraqi people to take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside.” However, once these rebellions began they were met with harsh and violent reprisals from the Iraqi Government and the American Troops, many of which were still in the country, sat idly by. In fact, the United States went even further with the deputy spokesman of the State Department, Richard Boucher, claiming that “we don’t think that outside powers should be interfering in the internal affairs of Iraq,” – despite having openly and brazenly encouraged these rebellions.

While slightly different from the ongoing situation with the Kurds in Syria – as there was not an explicit promise of aid – this was a brazen display of opportunism. Despite openly and strongly encouraging the rebellion, the US involvement was largely passive and self-serving, with George Bush saying that “The United States will not have normal relations with Iraq ‘until Saddam Hussein is out of there… But I made very, very clear from ‘Day One’ that it was not an objective of the coalition to get Saddam Hussein out of there by force.'”

By Jonas Jordan, United States Army Corps of Engineers – Public Domain

While the US was pulling out of Iraq in 2011, they orchestrated a second, similar betrayal. Many Iraqi citizens aided the coalition forces (consisting primarily of the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia) – by acting as translators, or working other civilian jobs during the Occupation of Iraq from 2003 to 2013. If these civilians remained in Iraq, they would be in danger since they were seen as having collaborated with the enemy. The United States had originally promised that it would issue visas to those at risk – but as time went on, and even today, fewer and fewer visas have been issued, with only two in 2019. The US acted likewise in Afghanistan, showing a similar lack of concern for those who had been working with the coalition forces. In both cases, the United States hesitated to make good on their promises, instead dragging their feet and endangering supposed allies.

The policy decision of pushing for rebellion and then refusing to intervene predates the Gulf War. In fact, one of the earliest modern examples of relevance is that of the Hungarian Revolution. In 1956, the Americans supported the Hungarian Revolution against the Soviets and pushed for a revolt, all the while making blanket statements that were interpreted by many as commitments to future military intervention. In several cases, Americans, using RFE broadcasts, implied that foreign aid would be forthcoming if the Hungarians succeeded in establishing a “central military command,” but the US never followed through.

Photo By FOTO:FORTEPAN / Pesti Srác, CC BY-SA 3.0,

From these examples, one can see that the United States has a long history of using local groups for self-serving purposes and then abandoning them when faced with domestic resistance. Given this, the recent choice to pull out of Syria and allow a Turkish invasion is not only unsurprising, but is, in many ways, par-for-the-course in how the United States deals with supposed allies. While politicians are certainly willing to criticize and debate this decision now, we should consider whether they would say the same about past instances where they acted similarly. If current and former members of Congress want to argue that abandoning the Kurds is dangerous and that it sets a precedent for current and future American allies, they should consider their past actions and the history of American exceptionalism that have already fed this narrative.

The feature image “Barış Pınarı Hârekatı’nda Tel Abyad bombalanıyor” by Orhan Erkılıç was sourced from the Voice of America and is licensed under Public Domain.

Edited by Nikita Buchko