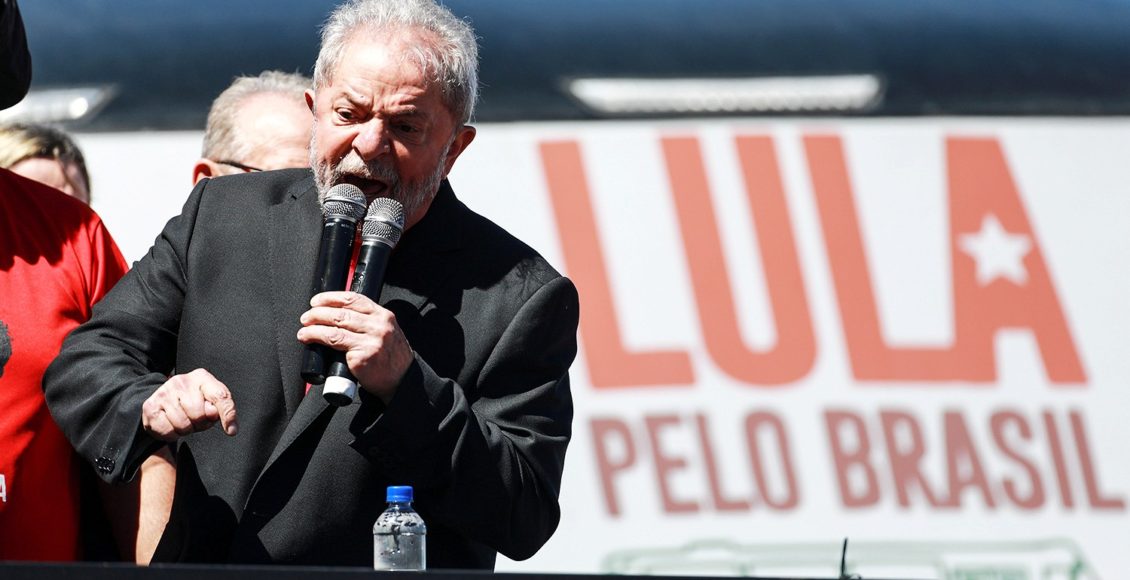

What Does Lula’s Release Mean for Brazil?

Lula" by Jeso Carneiro is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Lula" by Jeso Carneiro is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Brazil’s former President, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, “Lula”, was released from prison on November 7, after serving 580 days of an almost 9-year sentence on charges of money laundering and corruption. His release was a direct result of a Supreme Court ruling the day before that now permits convicted criminals to remain free during pending appeals. Lula had originally been sentenced to 12 years in 2017 as a part of Lava Jato, an investigation that uncovered a large-scale corruption scheme involving a semi-public oil corporation and many government officials.

First convicted in June 2017, Lula maintains that his convictions are “illegitimate.” His case has already processed numerous appeals, notably receiving a 3-year sentence reduction by Brazil’s Superior Court this year. Interestingly, Lula remains a hugely popular figurehead of the Workers’ Party (PT) today and was even the party’s primary presidential candidate while in prison during the 2018 elections. Only a Court decision in late August 2018 ended his candidacy under Lei Da Ficha Limpa (Clean Records Act 0f 2010), barring him from the October election due to his corruption charges. A famously polarizing figure in Brazilian politics, Lula’s release already appears to be mounting tensions concerning his de-facto leadership of the opposition, the legitimacy of his indictment, and his relations with the current administration.

Lula Livre pic.twitter.com/EJRrynjJjE

— Lula (@LulaOficial) November 8, 2019

Former Brazilian President Lula prepares to take on Bolsonaro’s current administration, following his release from prison earlier this month. (Translation: “Free Lula.”)

Power Politics in the Justice System

Lula’s release was made possible by Brazil’s Supreme Court narrowly ruling 6-5 to overturn its decision from three years prior. Since a 2016 ruling to change the Code of Criminal Procedure, the Supreme Court has held that defendants may be jailed should their first appeal uphold their conviction, regardless of other pending appeals. During the Lava Jato trials, this ruling incentivized defendants to take plea deals to reveal further information about the corruption, rather than test a justice system that would jail them after only one chance at an appeal.

Lula’s status as a former President and recent presidential candidate has blurred the lines between the Court and politics throughout the judicial process. Justice Gilmar Mendes noted publicly that Lula’s case has “contaminated” recent debate on the issue of appeals, while Lula himself remains steadfast in vocally accusing his opposition of weaponizing the judicial system against him. In both cases, what should be impartial judicial decisions, concerning a corruption investigation and, more recently, the federal appeals process, are widely interpreted as partisan rulings due to Lula’s involvement and his public narrative of victimization.

Lula is not the only politicizing factor: new revelations of judicial politicization by the prosecution have emerged, too. Sergio Moro, the judge who delivered Lula’s conviction in 2017, was heralded by Brazilian and international media at the time as the leader of an apolitical, anti-corruption crusade. However, a multi-part exposé by The Intercept Brasil in June of 2019 published leaked material and text messages among Lava Jato prosecutors and even Moro, himself. Such messages have provoked allegations that Judge Moro colluded with the prosecution in Lula’s conviction, by coaching the team of prosecutors and directing their media strategy.

Moro now commands a powerful position in the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro, former military officer of the conservative Social Liberal Party (PSL). By portraying himself as an anti-system candidate of the far-right wing during his campaign in 2018, Bolsonaro firmly grasped Brazilian’s distrust of the political class and their widespread economic insecurity. Distancing himself from any association with corrupt governments of the past, his policies stand firmly against the “socialism” of the PT years, railing against corruption and promoting a return to “liberal markets and family values.”

Following his anti-corruption rhetoric, Bolsonaro combined the ministries of Justice, Public Security, and Government Accountability under the singular direction of the Minister of Justice, and appointed Moro to fill this new role. Indeed, Bolsonaro’s election could possibly be credited to Moro’s decision to convict Lula of corruption, which was upheld under Ficha Limpa to bar him from the presidential race that he was leading. Following allegations that even Moro might not have been impartial, Bolsonaro’s whole administration is facing a crisis of legitimacy.

Lula and Political Culture

These recent revelations tap into existing allegations that Lula’s conviction was an illegitimate and political criminalization of the Left in Brazil. In a 2016 letter to UN Human Rights Committee, Lula was already claiming that the prosecutors and judge were using the legal system to wage a political attack against him. Ambiguities in the charges against Lula and these leaks regarding Moro and the prosecution only fuelled support from his base during his prison sentence. Now, using his renowned charisma, Lula is capitalizing on already pervasive anti-establishment sentiments in the Brazilian public to further push this narrative, in order to discredit the anti-corruption foundations of Bolsonaro’s government.

And of supporters, Lula still holds a sizeable backing from sectors of the Brazilian public. Lula left his two-term presidential tenure in 2010 with a huge 87% approval rating. Credited with lifting millions of Brazilians out of poverty through success in a commodities boom and large-scale social programs, the former leader still commands a cult-like following, especially among Brazilian working classes.

This phenomenon was illustrated in Lula’s lead in the 2018 presidential race: even from prison, being held incommunicado, he was nominated as the PT candidate and was leading the polls by double digits to Bolsonaro’s second place. Such numbers indicate that his vast numbers of avid supporters find his conviction irrelevant, whether they believe it to be illegitimate or simply negligible. Nonetheless, this means that Lula could remain a popular challenger to Bolsonaro’s tenure, especially upon his release and renewed campaign activities.

Lula’s release was celebrated around the world, too. Regional leaders, such as President Alberto Fernandez of Argentina, Ex-President of Chile Richardo Lagos, and Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, immediately showed their public support for Lula’s plight. Former French President François Hollande tweeted in support of Lula upon the release, stating, “Lula’s place was never in prison.” Upon Lula’s jailing in 2018, Bernie Sanders, Maxine Walters, and 28 other Congressional members wrote a letter against his imprisonment to the Brazilian Ambassador. It asserted, “The facts of President Lula’s case give us reason to believe that the main objective of his jailing is to prevent him from running in upcoming elections.”

La place de Lula n’était pas en prison. La liberté lui a été rendue, je sais qu’il la mettra au service du Brésil. @LulaOficial #LulaLivre

— François Hollande (@fhollande) November 8, 2019

Former President François Hollande tweeted in immediate support of Lula’s release.

A Polarized Country

While Lula holds high levels of support among some sectors, he also has one of the highest rejection rates among voters. His critics maintain that his programs neglected to attack the roots of Brazil’s political and economic issues, and instead fostered government corruption. In a political sphere so saturated with anti-corruption rhetoric, Lula’s ties to Lava Jato and the evidence that first convicted him mean that he remains untrustworthy to a large portion of Brazilians. In the aftermath of such a widespread scheme that resulted in the 2016 impeachment of PT President Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s leadership is preventing Brazil from moving on from this era of corruption by blocking the rise of new forward-thinking political leaders.

Firstly, Lula’s continued campaign activity and promotion by the PT prevents the emergence of a viable leftist challenge to Bolsonaro. As it stands, Lula’s candidacy is legally impossible: Brazil’s Clean Record Law blocks Lula from being eligible for elected office for 8 years following his first conviction in 2017. However, his refusal to step aside is also blocking the success of any other left-wing candidate who can run against Bolsonaro. The economic boom during his tenure and his historically high popularity levels as the first working-class president of Brazil means that Lula’s legacy is idealized by his party’s supporters and members alike. Thus, it seems that PT only want Lula, despite his conviction.

Also, Lula’s candidacy is likely to only further the political polarization occurring under Bolsonaro. While Lula held high rejection rates in the 2018 election, Bolsonaro’s rate of rejection by voters was 5 points higher. Bolsonaro is known for his offensive speech, often turning to homophobia, xenophobia, misogyny, and racism. He sparked international outrage over his neglect of the devastating fires in the Amazon this year and allegations of links to the murder of left-wing city councillor Marielle Franco. In his far-right rhetoric and anti-system policies, Bolsonaro has created large political divisions by provoking strong reactions across the board.

A free Lula only drives the Brazilian people further to the political poles. His ability to recommence campaign activities could increase the effectiveness of the opposition to Bolsonaro. Capitalizing on the current polarization, Lula launched a stream of rhetorical attacks against Bolsonaro’s divisive administration, urging Brazilians to take to the streets and “follow the example of the people of Chile, of Bolivia.” However, fighting against a convicted politician could boost support for Bolsonaro, too, especially to counter the new allegations of corruption. Doubling down on his anti-corruption stance, Bolsonaro has urged Brazilians “not give space to compromise with a convict,” labeling Lula as “momentarily free, but guilty.”

As Brazilians are forced to choose between a convicted hard-leftist and a pro-militarizing far-rightist, the public will only be further polarized. With anti-government protests currently sweeping parts of Latin America, Lula’s incendiary tactics could openly clash with the militaristic disposition of Bolsonaro, who requested authority from Congress in late November to stop potential violence with the use of armed forces. If Bolsonaro’s election was the product of political divisions over Lava Jato and Lula’s conviction, a more drastic political backlash could be in store over Lula’s release.

Edited by Chanel MacDiarmid.