Bobi Wine: An Unlikely Challenge to Status Quo Power in Uganda

A new opposition leader in Uganda is poised to achieve real political change. For the 37-year-old Bobi Wine, success in next year’s presidential election will not simply be defined by victory or loss. His candidacy, in channeling a grassroots youth movement and a fiercely anti-corruption message, promises a more high-profile threat to the status quo than at any previous point during the current administration’s reign. In that alone, Bobi Wine has already done the impossible.

Wine has served as a Member of Parliament for Kyadondo East Constituency since 2017, which he won in a by-election, but he did not always have political aspirations. He began his career as an actor and musician in the early 2000s, and his recent popularity stems largely from his pop star status. His hits include “Kiwane,” which landed on the soundtrack for Disney’s Queen of Katwe (2016); “Kyarenga,” the music video for which has been viewed nearly two and a half million times on YouTube; and “Situka,” which sends a socially conscious message about political activism and followed an eponymous film from 2015 which starred Wine. Born Robert Kyagulanyi in Uganda’s Kisenyi II slum, he took the name Bobi because it “sounds cooler” than Robert, and Wine, because like wine, he only improves with age. His upbringing earned him the nickname “Ghetto President.”

Throughout Wine’s life, Ugandan politics have never been truly competitive. President Yoweri Museveni has ruled for 34 years after gaining power in January 1986 and is currently the fourth-longest tenured leader in Africa. After a ten-year transitional period, Museveni first held democratic elections for five-year presidential terms in 1996, and he has since won five such elections. His administration has clung to power by repeatedly amending the constitution to enable Museveni to effectively solidify lifelong rule. In 2005, his administration abolished the two-term presidential limit ahead of the 2006 election, and in December 2017, they also scrapped the 75-year ruling age limit. Museveni will turn 76 in September.

As he vies for a sixth term in next year’s presidential contest, Museveni must contend with Bobi Wine’s rising popularity, both as an MP and as a symbol for the Ugandan youth. Wine won his 2017 election with a surprisingly successful door-to-door campaigning strategy, and defeated members of Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) and the central opposition party, the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC), with 77% of the vote. This is no small feat; the NRM, which Museveni led to seize control of Uganda after the 1980-1986 Bush War, has a strong electoral record amongst Ugandans and has never lost a majority in Parliament.

Wine, meanwhile, leads the less well-established People’s Power Movement in his presidential campaign, and he currently maintains Independent status in Parliament. He stresses the movement’s distinct identity as separate from his own political jurisdiction and leads it to remind Ugandans of their constitutional right to an equal stake in the nation’s political future, regardless of tribal affiliation or class. The novel movement is instantly recognizable by its red berets, which were banned by the government in September 2019. In its messaging, People’s Power explicitly targets youth supporters, who, like Wine himself, were born with no memory of Uganda’s pre-NRM history. Should he gain wide support amongst younger voters in 2021, he should expect to excel at the ballot box, given the huge concentration of youth in Uganda. Today, the current median age in Uganda stands at 15.7 years, the second-lowest figure in the world (ahead of Niger).

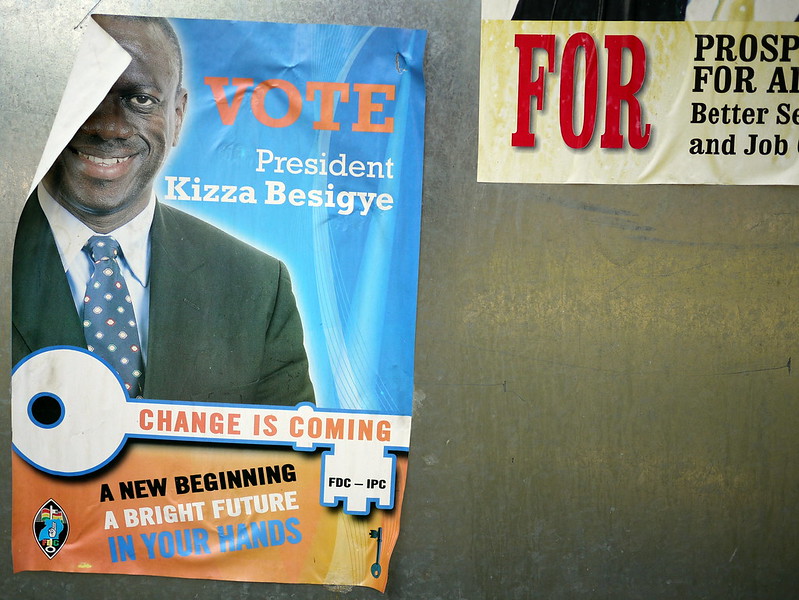

The road to victory is still uncharted territory, however, given Uganda’s history of political violence and electoral interference by the state. The police have arrested Kizza Besigye — the most prominent opposition leader and former leader of the FDC — four times throughout presidential campaigns dating back to 2001, on charges including inciting violence, causing a traffic jam, and holding campaign rallies without the government’s permission. The charges of violence have empowered police to respond in kind against Besigye and use tear gas and threats of physical violence to suppress his supporters.

The clearest evidence of electoral interference, however, came in the 2006 race, when Besigye was arrested for treason and rape three months before the election. The Ugandan Supreme Court found evidence of voter disenfranchisement, ballot box stuffing, and intimidation at the polls, but declined to reverse results; Besigye was cleared of all charges the next month. Similar tactics were used to suppress Besigye’s campaign in 2016 as well. Museveni’s victories have not always been landslides, however; Besigye earned 37.4% of the vote in 2006 and 35.4% of the vote in 2016.

Bobi Wine has faced similar violence and interference from the government. In August 2018, when supporters of an anti-NRM candidate in Arua threw stones at President Museveni’s motorcade, Wine was linked to the incident because of his support for the candidate and was charged for inciting violence, as well as illegal possession of firearms. Wine’s driver was killed, and then, according to Wine, police proceeded to beat and sexually assault Wine inside his vehicle. While the police eventually released him on bail, they charged him for treason separately in civilian court, and later charged him for “intent to alarm, annoy or ridicule” the president. Police have also prevented Wine from hosting campaign consultations and concerts to promote his presidential bid, even though the Ugandan Electoral Commission has approved his ability to do so; police fired tear gas at his supporters and detained him as recently as January 6th, alarming Human Rights Watch.

President Museveni himself, meanwhile, dismisses accusations of foul play. He rejects any responsibility for voter suppression and argues that the police are necessary to prevent youth protestors from rioting and damaging state property. Concerning term limits, Museveni has a straightforward approach, which he explained to BBC News: “If you don’t want [leaders] to be there forever, you vote them out. The real issues in Africa are not ‘who,’ they are ‘what.’ So we don’t accept the logic of term limits.” The president is confident in his re-election chances and he speaks to his strong record and identity as a liberator to secure victory. He took a widely publicized march in January to retrace the steps that he and his guerrilla fighters took in 1986 to seize the seat of government.

Bobi Wine’s pitch for the presidency strikes the opposite tone, and he asks Ugandans to reconsider their frame of reference in defining stability for their country. In an interview with Al Jazeera in September 2019, he urged international media to take his plight seriously: “To the western world, President Museveni has always cast this image of a ‘democrat,’ but back home, he has stepped on all rights and all freedoms, and he has ruled Uganda with an iron fist.” He also advocated for a truer relationship between Uganda and the West: “What unites us should not be only business, it should be the values that we share together. Values like democracy…respect for human rights, and zero tolerance [for] corruption.”

As Wine campaigns to upend what he argues is a fundamentally unjust government, President Museveni will look to stop his progress at every turn. Election day next February will be a referendum, not only on Museveni’s tight grip on political power, but also on the viability of an alternative candidate who speaks the politics of the young and disenfranchised. Such voters, who have never known a president other than Museveni, will play the largest role in shaping the next five years of Ugandan politics, and they will make or break Bobi Wine’s campaign. The young pop star-turned-politician represents a new generation of politics in Uganda and has made impressive inroads with voters through his defiance of the status quo and his appealing vision for human rights reform.

This article was originally published in the Kosciusko Review on March 23.

The featured image is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.